In the two years since Jeremy Ben-Ami founded J Street, which bills itself as a "pro-peace, pro-Israel" voice for a two-state solution to the Israeli/Palestinian dispute, his organization has been attacked as "morally deficient" and "appallingly naive" by critics in the American Jewish community and on the right end of the political spectrum. And in Israel, members of the Knesset have even formed a committee to determine whether J Street is "anti-Israel" and should be publicly condemned.

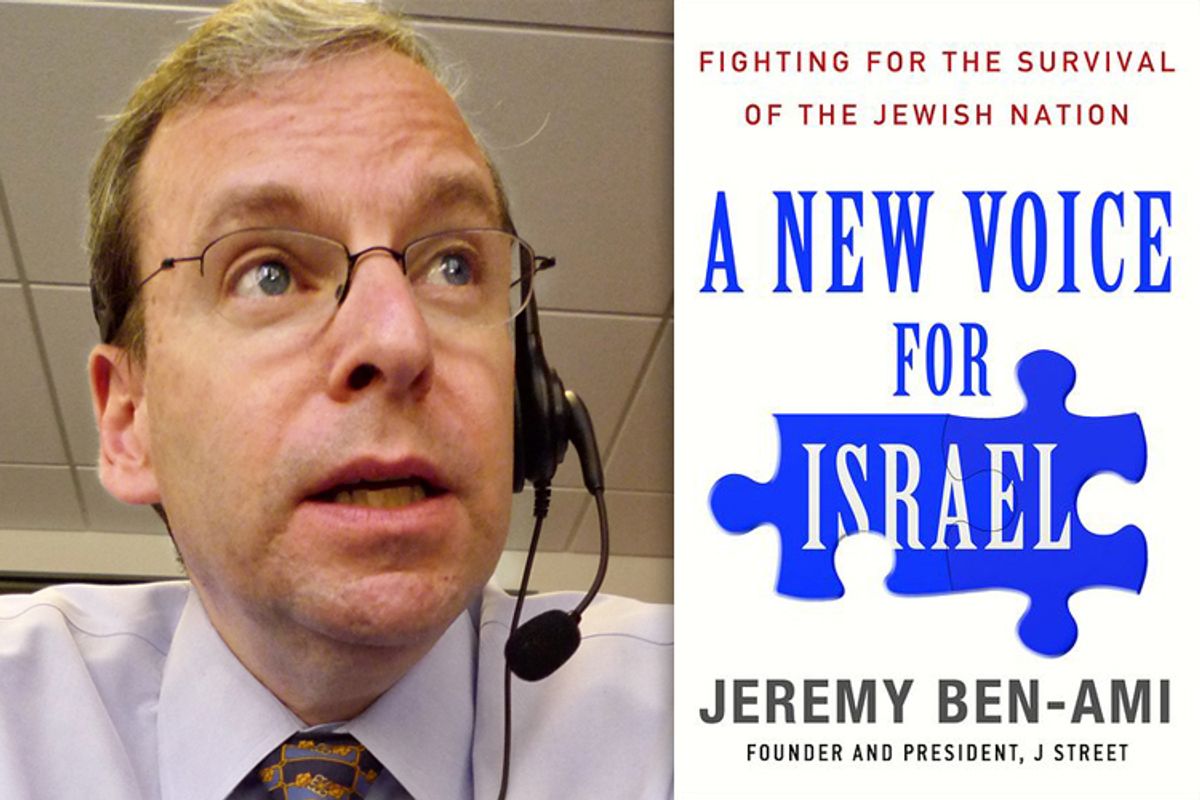

In his new book, "A New Voice for Israel: Fighting for the Survival of the Jewish Nation," Ben-Ami confronts his critics and presents his case for what, exactly, has gone wrong in Jewish politics both here and in Israel. The fundamental problem, as he sees it, is that the existing pro-Israel establishment isn't willing to apply the pressure needed to bring about an end to Israel's dead end occupation of the West Bank and the creation of a viable, peaceful Palestinian state.

We caught up with Ben-Ami recently and discussed the challenges J Street has faced in trying to convince Jewish-Americans to think differently about a country they've been taught to support unconditionally.

You compare your own struggles as a minority voice in the Jewish community with those of your father, who was an active member of the Irgun, a right-wing Zionist military group, in the 1930s and '40s. What parallels do you see?

I found the similarities in the way in which our experiences played out to be really shocking. [In both situations,] you have an establishment with a certain point of view, and you have a voice of dissent that wants to come into the conversation -- and that voice of dissent is warning of impending disaster. And rather than dealing with the substance of the contentions that are being put on the table by the minority, the majority and the establishment tries to quash their voice and uses whatever tactics are at its disposal.

In my father's case, [they tried] to wiretap their operations, and bring the U.S. government in to investigate them. It was amazing, the things that were done to shut them down, rather than allow them into the debate. And I just see that as extremely similar to the tactics that are being used against J Street, and that have been used for years against many groups over the last several decades that have talked about a need to approach the [Israeli-Palestinian] conflict with anything other than an "us vs. them" mentality. The funding threats are there -- groups are told by donors, "you can't host these speakers or I'm going to pull my funding from you." [There are] the personal attacks, the lies and the smears and all of this crap that gets thrown at you, which has nothing to do with what [points] you're actually raising. The ways in which an established power base tries to shut down voices of dissent was just extraordinarily parallel [to my father's experience]. It's the same exact dynamic.

I recently watched a video of your 2009 debate with Alan Dershowitz, and was struck that you didn't appear to actually disagree on the policy subjects that you discussed.

The biggest difference on a substantive level is this: AIPAC is what I call ... a passive supporter of a two-state solution. We [at J Street] say we're pro-Israel, pro-peace and the other side goes nuts because they say, "we're pro-peace too." And of course they are. [Laughs] There really are very few pro-war people, and there are only really a handful of people who would publicly admit that they don't support a two-state solution at this point. The question is whether or not you view the need for a two-state solution as such an existential necessity that you actually have to actively promote it and pursue it. And that I think is the fundamental fork in the road.

AIPAC's [mentality is], "Look, Israel's doing just fine. We should continue supporting it." And we are sounding the alarm bell. We are shouting as loudly as we can, "You are heading off a cliff!" That's a huge difference. And you know, AIPAC and J Street could agree on 80 percent of policy, but this is the issue. It is the defining issue, and that's what separates us. We want to see Israel survive, and unless active changes are made, Israel is not going to be able to exist as a Jewish and a democratic homeland within a couple generations.

So why do certain Jewish-American organizations find you so threatening? The reaction does appear to be overblown, as an outsider.

[Laughs] Well, it looks overblown to an insider too.

[laughs] OK, let's just say it's overblown.

Right, exactly. I always say there are two factors that always really go into the antagonism. One factor is ideological, and the other is institutional. On the ideological front, 20 percent of American Jewry and maybe 20-30 percent of Israeli Jews are really right-wing -- really hate Arabs, don't believe the Palestinians exist as a people, think this is all some plot to push Israel into the sea. So they are just ideologically opposed to what we stand for in terms of policy. They are obviously very prominent in Israel ... you know, people who think we are so wrong that what we are doing is leading to the destruction of the state of Israel. Just like I believe that they are so wrong that they are leading to the destruction of the state of Israel.

There's a second piece of this, though, that is institutional, and it's those process-oriented arguments that are a bit opaque to the casual observer. The very concept that the Jewish community in the United States doesn't need to speak with one voice is really disturbing to a lot of people -- particularly those from an older generation. You know, the mind-set that we're just a small minority in this country and really can't risk our political power ... It's not good for the Jews to split the community into two voices, it's not good to diffuse our power and to have a congressman or senator or policymaker confused as to what the Jews think; if we're sending mixed messages, we're going to lower their commitment to Israel and it's going to be bad for Israel in the long run.

And there is a piece of [the institutional argument] too that's not as nice -- this is about power. For two generations, one institution has had the power, one set of voices has had the power, and here comes the competition. And what do monopolies do? They try to destroy the competition. You add all of that together and you get a pretty venomous mix.

Is the conversation within the Jewish-American community beginning to change? I would imagine that younger generations of Jews are more receptive to it.

I don't like to over-generalize. There are more orthodox young people than orthodox old people, so if you just look at age, younger American Jews are actually slightly more conservative and right-wing on Israel than older Jews. It's totally counterintuitive, right? And young liberals don't like to hear it ... So you have to segment out the non-orthodox younger Jews -- and that segment is very different. They don't get many of the basic premises on which this whole issue [of Israel] has been constructed and built over the last two generations. They don't get the idea of being a powerless minority, and needing to speak with one voice in order to conserve your power -- they only know Jews as an extremely well-integrated and pretty powerful part of American society. The concept that we need to be careful and not let other people see our disagreement makes no sense to younger people. And I do think that some of the emotional understanding about the need for a homeland for the Jewish people is harder for younger people to grasp. The visceral defensiveness that comes in among 60-year-olds, 70-year-olds, [Jewish people] my age even, that we really need to protect and defend this little country -- that instinct just isn't quite as natural for people 20, 30 and 40.

What about the Arab Spring? Has that affected the conversation in a significant way?

There are two conflicting effects, I think. One is the natural circle-the-wagons defensive reflex reaction that people have in situations where there is instability and uncertainty. The outcome of all of this is unclear. Will these new governments still want to pursue peace with Israel? What happens if you sign a peace agreement with the King of Jordan and he's thrown out? That sense of insecurity reinforces the instinct to be conservative and say, "Well, in the end we can only look to ourselves."

The other thing that happens, though, is I think there's a real resonance with the values that a lot of the sparks that led to this were based on notions of democracy, freedom from oppression -- and all of that really resonates with Jews, particularly in the United States. So I think on one hand you have a lot of hope in part of the community, and then you have a lot of fear. And those two reactions are kind of at war with each other -- within individuals, and within society.

Shares