It's been nearly 20 years since an erratic Texas billionaire with a fondness for charts and a paranoid sensibility became an overnight political sensation, briefly emerged as the leading candidate for president of the United States and wound up securing nearly 20 percent of the national popular vote.

And now, for the first time since that 1992 election, the conditions that made H. Ross Perot's unlikely rise possible are again poised to shape a presidential election.

It takes a lot for a truly credible independent candidacy to take off. There are a few third-party options in every national election, and sometimes even big names step forward -- like Eugene McCarthy in 1996 or Pat Buchanan in 2000. But almost always, they go nowhere. McCarthy, a two-term Minnesota senator who helped take down Lyndon Johnson in the 1968 Democratic primaries, attracted just 0.9 percent when he went outside the two parties, while Buchanan got 0.4 percent when he tried it. And while Ralph Nader's campaign in '00 may have been consequential, he still failed to attract even 3 percent of the vote.

If an independent candidacy is going to break through, it's very helpful, if not necessary, for a few specific conditions to be present: 1) An incumbent president; 2) intense economic anxiety that creates broad dissatisfaction with the president; and 3) a popular sense that the opposition party has nominated an unacceptable alternative.

This is how it has worked in the modern era of presidential elections, which has included two races with serious third-party presences.

The first was in 1980, when double-digit inflation and interest rates conspired to lower Jimmy Carter's approval rating to poisonous levels. Voters badly wanted him out, but the GOP didn't make it easy for them, choosing to nominate Ronald Reagan, who was then widely seen as a dangerous, trigger-happy ideologue. It was then that John Anderson, a liberal Republican congressman who had vied with Reagan for the GOP nomination, stepped forward and offered himself as an independent candidate. Initially, the interest was high: In the spring of '80, Anderson found himself polling 24 percent of the vote, and talk that he might win some states wasn't considered unreasonable.

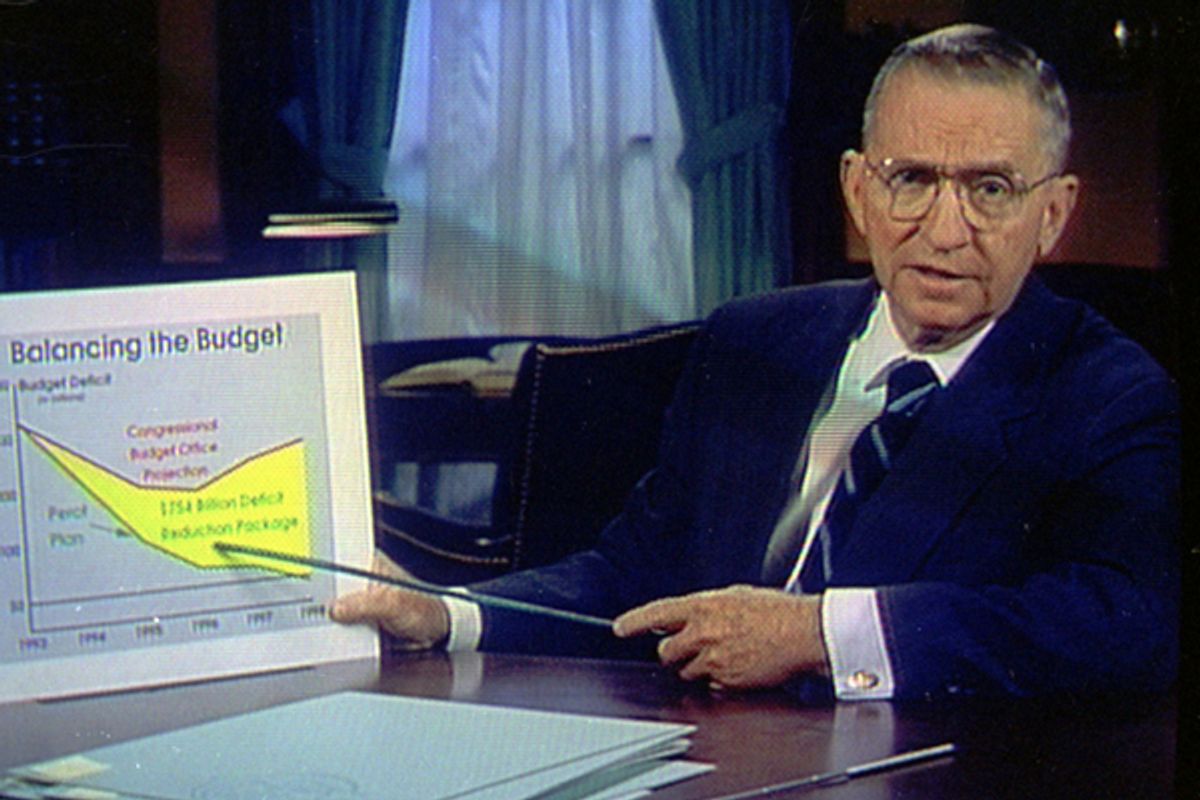

The situation was fairly similar in '92, when a recession had voters itching to fire George H.W. Bush. But Democrats were forced to settle on a man who was then seen as a profoundly weak and flawed candidate: Bill Clinton, who made it out of the primary season mostly by default, having endured a series of damaging personal scandals. This is why there was an instant, wide appetite for Perot, then a largely unknown billionaire with a gift for populist rhetoric, when he announced late in the winter of '92 that he'd be willing to run if a draft movement put him on the ballot in all 50 states. By the end of May, he was running in first place in national polling, with nearly 40 percent of the vote -- slightly ahead of Bush and nearly doubling up Clinton.

Of course, both Anderson and Perot eventually slipped from their peaks, and there's another lesson in this: Even when there's a broad desire for a third choice, voters still tend to fall back on the two major candidates, for fear of wasting their ballots. Anderson slumped all the way back to 7 percent on Election Day, while Perot -- who dropped out under truly bizarre circumstances after his star began dimming in the summer, only to reenter the race at the start of October -- claimed 19 percent.

But each was a serious player in the race. Anderson managed to finagle an invitation to a debate with Reagan (Carter, believing that Anderson was cutting into his support, refused to attend), while Perot made it into all three debates, spent lavishly on 30-minute infomercials, and helped make the national debt (then $4 trillion) a leading issue. Neither, though, affected the ultimate outcome. Exit polls in '80 showed Anderson's voters favoring Carter over Reagan as their second choice by a 49-37 percent spread -- this in an election Reagan won by 10 points and with 489 electoral votes. And, despite two decades of claims to the contrary by Republicans, there is absolutely no reason to think that Perot disproportionately took votes from Bush. (In fact, the '92 exit poll actually found that Perot voters were slightly more likely to favor Clinton as their backup choice.)

In the four elections since '92, independents have utterly failed to gain the kind of traction Perot did. Perot himself tried in 1996, but he never made a move in the polls, was largely ignored by the press and shut out of the debates, and couldn't muster even half of the support he'd received four years earlier. In '00, Buchanan and Nader tried and couldn't crack 4 percent between them, while in 2004, George W. Bush was more of a polarizing incumbent than an unpopular one -- voters wanted a referendum on him and his post-9/11 policies, not a third choice. And in the open seat race of 2008, just all of the energy was contained within the two parties.

But 2012 looks like it will be different. Even the White House is forecasting that unemployment won't drop below 9 percent before Election Day, which means Barack Obama's already feeble job approval numbers probably won't improve much before then either. Which means that there will probably be a broad desire to replace him -- and it's hard to imagine that, at least initially, Republicans will produce an acceptable outlet for that desire.

On Thursday, NBC's Chuck Todd speculated that if Rick Perry were to emerge as the GOP's choice,

"I think there's going to be be a serious effort of some sort of moderate Republican linking up with a conservative Democrat of trying to run in some sort of like, 'Let's throw all the bums out -- let's crash the party,' you know, à la Perot …"

The potential for something like that clearly exists, although as Jonathan Bernstein noted, it will probably also exist even if Mitt Romney is the Republican candidate. While Romney is generally seen as the more moderate, swing voter-friendly GOP option, his party remains profoundly unpopular, and it's not like there's much built-in affection for him among general election voters. So the chances are good that no matter which option Republicans go with, there will be room for a credible third candidate to step forward and generate an unusually high level of support -- and, at least potentially, to sway the outcome on Election Day.

Of course, whether anyone actually will step forward is another matter, and how a third candidate might affect the two-party race is a complicated question that depends on factors we don't yet know. Presumably, though, the name of Michael Bloomberg, everyone's default third-party option, will get some attention. But as Anderson and Perot both showed, it doesn't necessarily take a glamorous name to arouse the public's curiosity when the climate is right.

Shares