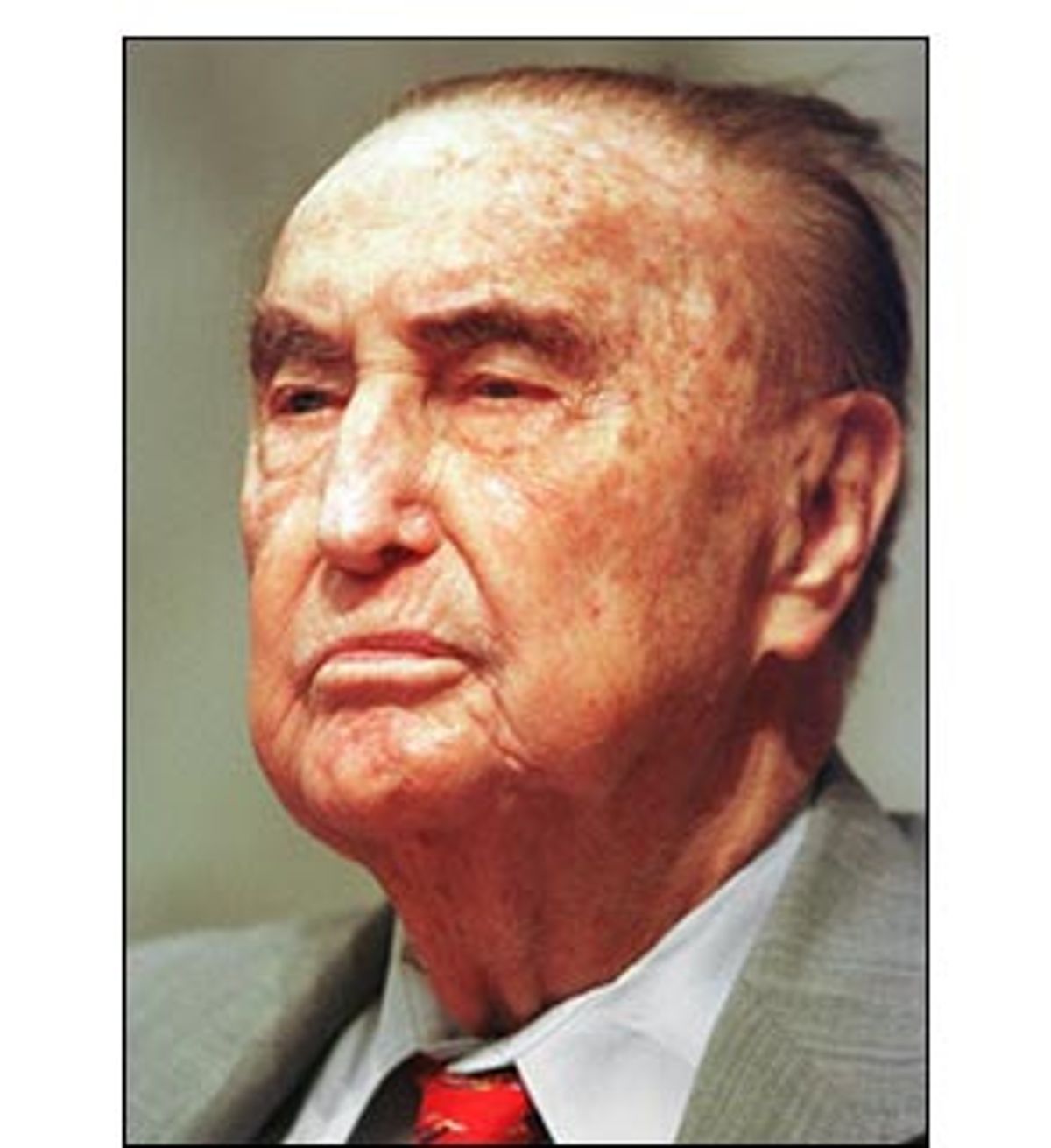

Prominently displayed in the Washington offices of Sen. Strom Thurmond, R-S.C., is a 3-by-4 foot wooden display case crammed full of mementos from his 70-plus years in politics. Scattered among the campaign trinkets and snapshots are newspaper articles, the more recent ones at the front spotlighting his work with President Ronald Reagan, the older ones near the back testifying to a part of Thurmond's career many of his admirers prefer not to speak about: cartoons glorifying his abandonment of the Democratic Party in 1948, which was prompted by President Truman's drive to integrate the military; banner headlines trumpeting his now-infamous filibusters of voting-rights legislation for blacks.

Since winning as a write-in candidate in 1954, the 98-year-old Thurmond has lasted so long in the Senate that he's outlived much of the vitriol he spewed and inspired as a segregationist firebrand. Now, his flaws are consigned to history, and his fans make him out to be a symbol of the South's legacy and reinvention. "Where Strom Thurmond has gone, the South has followed," said J. Sam Daniels, executive director of the South Carolina Republican Party. "He's a mythical figure to us. It will be a tremendous loss when he leaves."

Nonetheless, speculation about that possible loss ranks as a political pastime just behind the ongoing mutterings about the health of Vice President Dick Cheney. The Republican Party has a lot vested in Thurmond's health these days. Should Thurmond leave the Senate, or die, before his term ends in 2002, his replacement would be chosen by South Carolina Gov. Jim Hodges -- a conservative Democrat, but a Democrat all the same. Hodges would very likely appoint a Democrat, though some South Carolina Democratic officials jerked the national party's chain this week by telling Time that Hodges just might tap a Republican. But if Hodges does stay loyal to his party, suddenly the GOP's precarious control over the Senate (a 50-50 tie capped by Vice President Cheney's tie-breaking vote) is gone, and its seemingly iron-clad grip on Capitol Hill is gone with it.

Hodges' office disdains such talk. "That's not something that the governor likes to think about," says Morton Brilliant, his deputy chief of staff. "Senator Thurmond is more than a beloved figure in South Carolina," he scolds. "He's a real living man with a wife and children. We think it's morbid and unfortunate to talk about replacing him."

Sure it is. But it's also inevitable, and was made more so after Hodges met with Thurmond's estranged wife, Nancy Moore Thurmond, last fall. A South Carolina newspaper, the State, reported that Nancy Thurmond gave Hodges a videotaped message from the senator in November in which he declared that, should he die or leave office before his term expires, he would like his wife appointed to replace him.

Brilliant acknowledges that Nancy Thurmond met with the governor just before Thanksgiving, but denies any knowledge of the tape, and changes the subject again: "We expect to be working with Senator Thurmond until his term ends in 2002."

But recent reports about the senator's health have cast doubt on that. He's been in the hospital five times since May, and that's a tough fact for his press secretary, Genevieve Erny, to spin. "Whenever he goes in, they can't find anything really wrong with him," she says. "He's really in great shape for someone his age."

There's nothing wrong with Thurmond that a two- or three-day stay in a hospital hasn't cured, Erny insists. Still, no matter how many reassurances Erny offers to the press, she's periodically inundated with constituents' calls of concern about Thurmond's health, and much less delicate inquiries from reporters. "A lot of them are writing his obituary," she says with a bemused smile.

Erny and Thurmond's 25 other staff members form a famously tight-lipped team headed by R.J. "Duke" Short, Thurmond's chief of staff for 27 years. Thurmond has long stopped giving extensive interviews. Right now, Erny says, he'll occasionally speak with a few South Carolina reporters, and that's it. No one on his staff except Erny is allowed to talk to the press.

The same woman has been keeping the senator's schedule over two decades, and a cadre of assistants and researchers, who Erny politely insists go unnamed, help keep Thurmond's days running smoothly. The senator's chauffeur usually escorts Thurmond from his car to his first stop of the day at the Capitol at around 9:30 a.m., where his personal assistant offers an arm for Thurmond to lean on -- literally -- throughout his daily rounds.

Erny is quick to point out that the personal assistant is not only Thurmond's human walker but is an aide with administrative responsibilities. She also dismisses persistent rumors that Short is the real power behind Thurmond's throne. "The senator makes all his decisions himself, and he almost always works a full day."

Surely that was the case on a day last week, when Thurmond headed straight from his office to the Capitol to mark up a bankruptcy reform bill. In the afternoon, he granted an audience to a pack of reverent eighth-graders and worked on policy matters before heading back to the Senate floor, where he called out a "yea" vote confirming a second-tier treasury nomination.

He headed home shortly after 6 p.m. The vote was his only public comment of the day.

What's really on Thurmond's mind, as his long, often ugly and certainly historic political career winds to a close, remains a mystery.

Shares