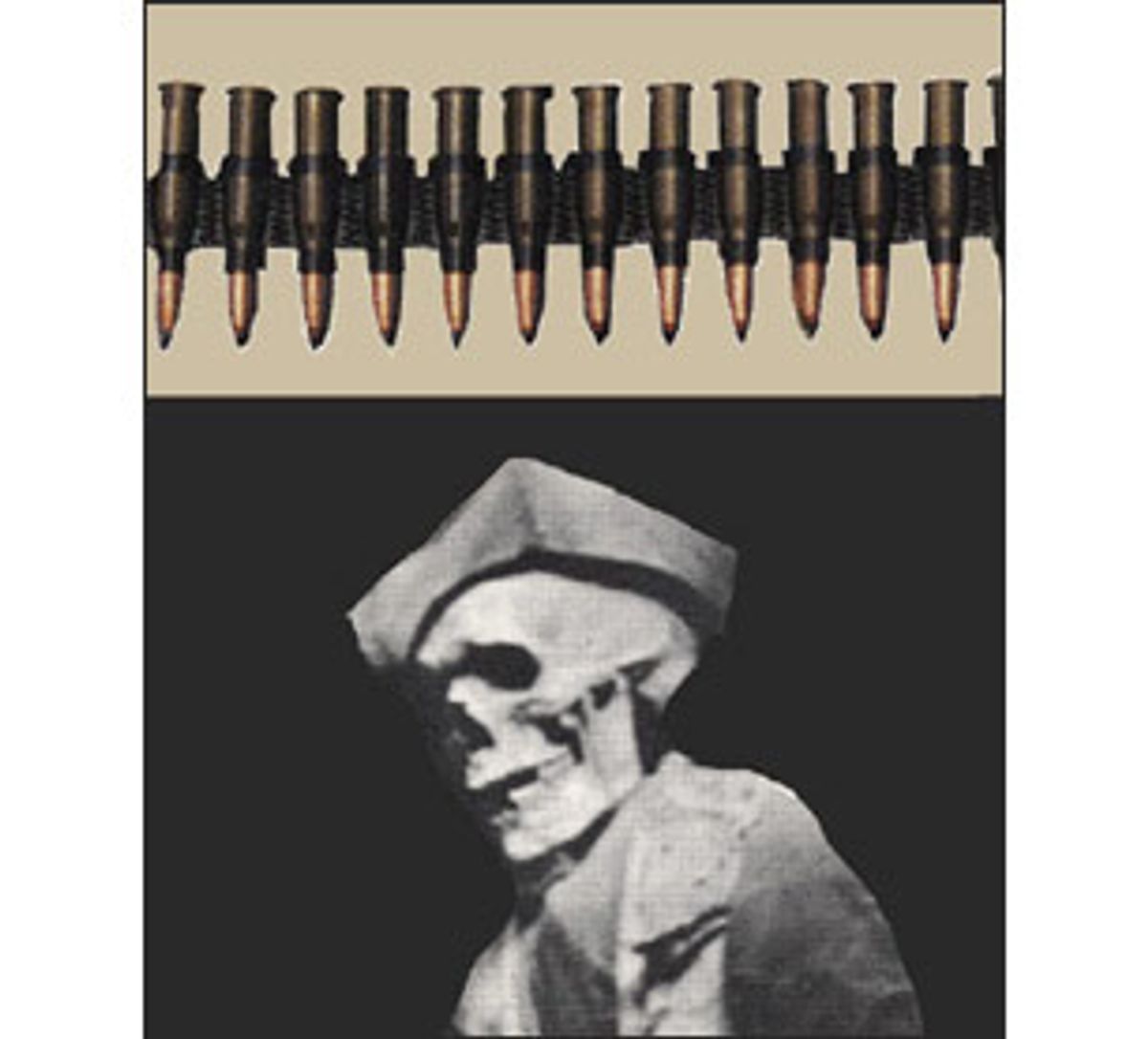

How does it feel to kill another human being? Murderers are often only too

eager to tell, in jailhouse interviews or macabre memoirs. But soldiers --

ordinary men who kill for their country, willingly or not -- are less

loose-lipped. The reason for their reticence is frequently what cultural

critic (and World War II veteran) Paul Fussell has called the "eloquence problem":

"Most of those with firsthand experience of the war at its worst were not

elaborately educated people," he points out in his classic essay "Thank God

for the Atom Bomb." "Relatively inarticulate, most have remained silent about

what they know."

But not all. In her new book, "An Intimate History of Killing: Face-to-Face

Killing in Twentieth-Century Warfare," British historian

Joanna Bourke brings us accounts of killing in battle that are frank,

forthright and, yes, even eloquent. Drawn largely from the letters and

diaries of rank-and-file soldiers -- the scrubs, the grunts, the guys on the ground -- the book offers a revealing glimpse into military history. Although

the impressions and attitudes of the elite are well-documented in every era,

Bourke has noted that working-class people usually only write letters during war. These dispatches provide rare insight into the experiences of men who may have scrawled in the foxhole or the barracks thoughts that they would not, or could not, convey once they got home. And no wonder -- since many such thoughts articulated the pleasure, the

near-orgasmic ecstasy, that some of these men discovered in killing.

"Gorgeously satisfying," "joy unspeakable," rhapsodized two of Bourke's

correspondents. Some descriptions of this perverse thrill are flip and full

of bravado -- "For excitement, man-hunting has all other kinds of hunting beat [by] a mile," declared Sgt. J.A. Caw -- while others display a chilling serenity.

"I secured a direct hit on an enemy encampment, saw bodies or parts of bodies

go up in the air, and heard the desperate yelling of the wounded or the

runaways," reported British soldier Henry de Man about a World War I raid. "I had

to confess to myself that it was one of the happiest moments of my life."

If many of these letters and journals reveal a gloating indifference to

human life, they're also full of the trembling vulnerability bestowed by

guilt. "To tell you the truth I had a tear myself, I thought to myself

perhaps he has a Mother or Dad also a sweetheart," wrote Pvt. Daniel John

Sweeney to his fiancie after shooting a German soldier. "I was really sorry I

did it but God knows I could not help myself."

After a fighter from Northern Ireland bayoneted a German without a twinge of conscience, commenting that his opponent "squealed like stuck pig," he was later struck by the magnitude of his action. "It was not until I was on my way back," he wrote, "that I started to shake and I shook like a leaf on a tree for the rest of the night."

What else did these soldiers set down in writing? Many raged against brutish or incompetent officers, at insufferable conditions and even at bloodthirsty civilians who clamored for war without knowing its costs. Others expressed frustration at the

remoteness, the impersonality of modern-day warfare (despite her title,

Bourke concedes that most of this century's wartime killings were anything

but intimate). There are ample testimonials of their love and loyalty to their fellow men. And sometimes they even show surprising sympathy and tenderness toward the enemy.

These men's responses to war, and to the act of killing in particular, are as

varied as their temperaments, their characters and their individual histories.

So it's disheartening to see Bourke try repeatedly to force their ragged,

irregular reactions into a single, smooth mold. "With occasional exceptions,"

she pronounces, "most servicemen killed the enemy with a sense that they were

performing a slightly distasteful but necessary job." Where in this bland

generalization, the reader may wonder, is the bloodlust of the man who wore a

necklace of ears cut from his Vietnamese victims? Where is the wrenching guilt of the

fighter who confessed that "after each mission I would vomit for hours and

beg God to forgive us for what we were doing"?

Bourke also airbrushes out details about the men themselves: their ages,

their military ranks, their hometowns. The soldiers' voices, as affecting as

they are, come to us oddly disembodied, like letters floating down from the

sky. But the book's most serious slip is its careless conglomeration of

British, American and Australian soldiers, fighting in the world wars and Vietnam.

Bourke often fails to identify a speaker's nationality and, on occasion, even

the war in which he served. Surely it's a radically different experience,

with distinct social and historical import, to be a Briton deep in

the trenches of the Somme or a G.I. landing on the beaches of Normandy or an

Australian skulking through the jungles of Vietnam. But Bourke would have us

believe that the experience of war, a great, granite-faced monolith, is essentially the same for every individual in every era.

Exasperatingly, Bourke points out the pitfall that lies before her, then

proceeds to jump right in. "Intimate acts of killing in war are committed by

historical subjects imbued with language, emotion and desire," she emphasizes

in her introduction. That rich specificity, however, is soon subsumed by

Bourke's own desire to reduce the experience of fighting in wartime -- a human

endeavor at least as emotionally complex and varied as having a childhood, or

falling in love -- to a simple formula. In one particularly murky passage, she writes: "There is no 'experience' independent of the ordering mechanisms of grammar,

plot and genre and this is never more the case when attempting to 'speak' the

ultimate transgression -- killing another human being."

It's the specifics that make this book valuable -- as when Bourke notes that when trauma (and not lack of learning) rendered these warriors wordless, their bodies spoke for them. "Soldiers who had bayoneted men in the face developed hysterical tics of their own facial muscles," she reports. "Stomach cramps seized men who had knifed their foes in the abdomen. Snipers lost their sight."

That's the kind of needle-sharp detail that ushers us into the vivid,

fantastical world of war as it felt to fight it -- a world that dims

and wavers whenever she returns to her flat generalizations.

Bourke's writing is mercifully free of academic or military jargon, and it is

occasionally gratifyingly fresh, as when she writes that even though "the

martial imagination was obsessed with jabbing and stabbing," "bayonets were

more likely to be stained with jam than blood." But more often her prose is

dull and repetitive, and in its diffuseness obscures as much as it reveals.

In this book, at least, the eloquence problem is the author's alone.

Shares