Meet the new savior of the California Republican Party: a politician who gave money to California Gov. Gray Davis, endorsed liberal Democrat Bill Lockyer for attorney general and Democrat Dianne Feinstein for the U.S. Senate -- twice. A man who ruled Los Angeles, forging alliances with Latinos and organized labor. A man who is pro-choice and an advocate for gay rights.

With their numbers in steady decline, California Republicans are increasingly turning to Los Angeles Mayor Richard Riordan as their best hope for challenging Davis in the 2002 gubernatorial election. An aggressive draft-Riordan effort is underway, and the mayor is expected to announce a gubernatorial exploratory committee in mid-July. That's encouraging news for the ideologically diverse posse of conservative and liberal Republicans coalescing around this unpredictable politician, who has what many would term questionable GOP credentials.

Still, Riordan's candidacy may be the best hope for breathing new life into California's floundering Republican Party, which is still coping with the end of the Reagan revolution. In the past eight years, the party has lost control of the governor's office, the state Assembly and all but one of the statewide elective offices. Democrats enjoy nearly veto-proof majorities in both legislative houses, and both of the state's U.S. senators are Democrats. The last Republican presidential candidate to carry the state was George Bush, in 1988.

All this has not been lost on the White House. Earlier this month, President Bush called Riordan to urge him to enter the race. Choose your own best reason for the White House involvement: For starters, Riordan would immediately become the strongest candidate in the field, and any chance Bush has of carrying the state in 2004 would be made easier with a sympathetic governor. The leading declared GOP candidate, California Secretary of State Bill Jones, endorsed Sen. John McCain in the 2000 California primary. And clearly, the White House would love nothing more than a bloody race for Davis, who has been a persistent thorn in its side. And, of course, if Davis is reelected, he will be increasingly mentioned as a possible challenger to Bush in 2004.

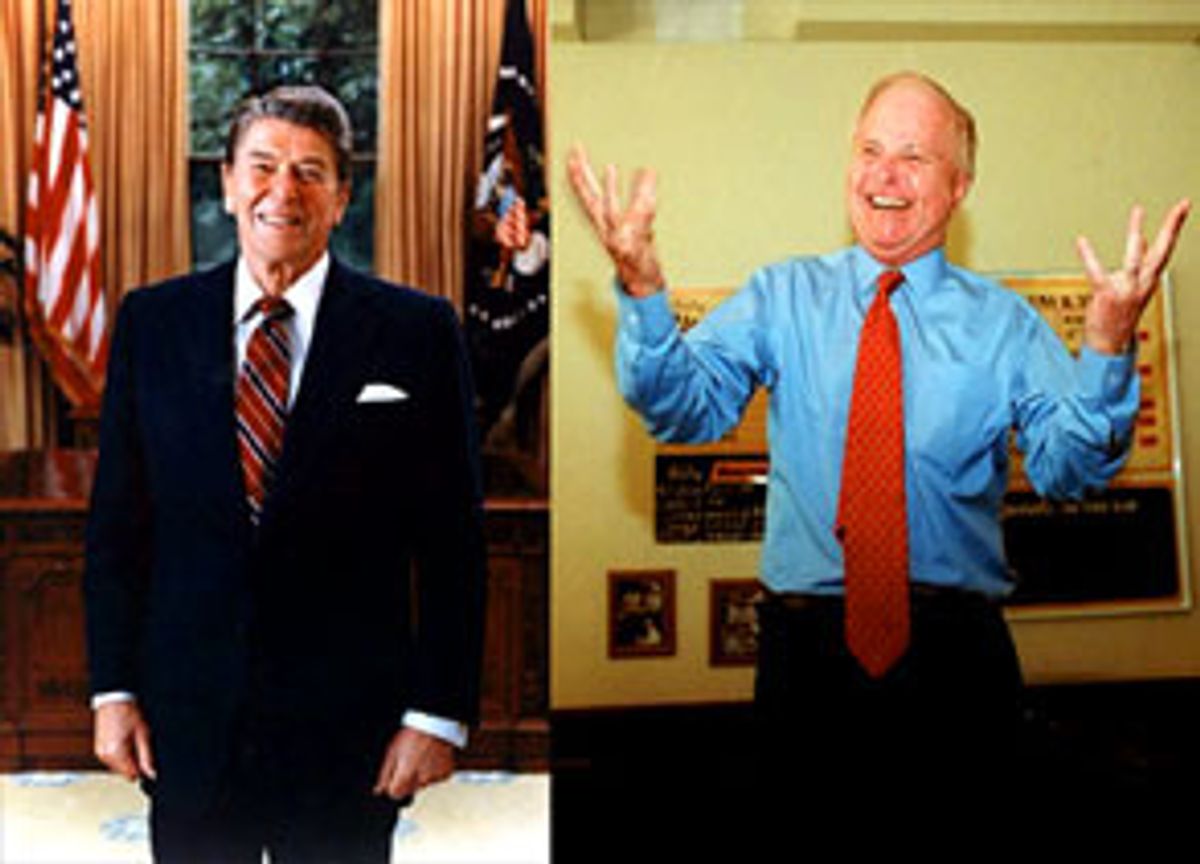

Riordan's increasing support among California conservatives -- Reps. Dana Rohrabacher and David Dreier are among those who have endorsed his candidacy for governor -- and moderates speaks to the slowly swelling discontent within California's Republican Party. The party of Reagan, with its Sun Belt social conservatism and strident anti-communist and anti-government mantras, is searching for an identity. Reagan dominated the political landscape in the state for more than two decades, from his first gubernatorial run in 1966 to the end of his presidency in 1988, fusing pro-business, anti-government proselytizing with a strong social conservative push to forge a new political majority in the state.

It took 10 years for the national Democratic Party to come to terms with this sea change, but by the early '90s it had, moving to the center under the leadership of the Democratic Leadership Council. Similarly, Republicans, without a leader of Reagan's charisma to reunite the party, are now struggling with the post-Reagan consensus that has formed in California.

California's dramatic demographic shift -- most notably an explosion in the Latino population and a doubling of Latinos as a percentage of the state's voters -- has also changed the political landscape. California voters are now overwhelmingly pro-choice, and seek to balance business concerns with environmental protection. Government is no longer seen as the monster it was under Reagan, and is increasingly deemed to be part of the solution as issues like education and healthcare rise to the top of the list of California voters' concerns.

As Democrats have moved toward the center, Republicans have been left with the less politically palatable fragments of the Reagan revolution. And for the past decade, an ongoing debate within the party has been whether the GOP should continue fighting for those fragments or shelve some of the issues -- notably abortion and strident anti-environmentalism -- in favor of more moderate positions.

Cue Richard Riordan. Of course, there is no guarantee that the 71-year-old outgoing mayor will enter the race, though his supporters say it's increasingly likely. The draft-Riordan movement was sparked when the Field Poll, released this spring, showed Riordan in a dead heat with Davis, while declared GOP candidates Secretary of State Jones and Bill Simon Jr., millionaire son of Richard Nixon's Treasury secretary, trailed far behind.

"I'm going to think very long and hard about it," Riordan said in a recent interview with the San Diego Union Tribune. "I really don't know ... My focus right now is on the city."

If Riordan does enter the governor's race, the GOP primary will be an overdue referendum on the party that Reagan built. The implicit questions: Is the Reagan coalition simply a relic of an old California? And are California Republicans ready for Riordanism to replace Reaganism?

"Not in my lifetime, that won't happen," says Ken Khachigian, a former top Reagan strategist who is less than thrilled by the prospects of a Riordan gubernatorial bid. "I think it would take some kind of mass blood transfusion for Reaganism to end."

But one GOP consultant who requested anonymity says the interest in Riordan among conservatives shows "there is a maturing in the party and the realization that this is no longer Reagan's California."

That doesn't mean that it's necessarily Riordan's, either. "I don't even know what Riordanism is on a statewide level," Khachigian says. "What mayors do in municipalities is not quite the same thing they would do when they're running a state."

While the speculation about Riordan swirls, Jones stands as the conservative standard-bearer-in-waiting. He's the loyal lieutenant in a party with a history of rewarding good soldiers. But the California GOP is in desperate need of generals. Some may view Jones' post-New Hampshire switch from Bush to John McCain as something of a betrayal, but he is widely acknowledged as a very good secretary of state, and has carried the mantle of the Republican Party as it has crumbled around him. If there is a GOP reward for simple survival, Jones deserves it. Certainly there is a case to be made that this is Jones' turn, even if doubts remain about his electability. Call him the California Republican Party's version of Bob Dole.

Jones has made clear he is willing to fight for the party's nomination, throwing a right-hand jab at the L.A. mayor earlier this month. "While Dick Riordan was donating money to Democratic candidates ... in 1998, I was standing proudly, shoulder to shoulder, with our Republican candidates," Jones said. "Unfortunately, I was the only one who won." (Actually, insurance commissioner Chuck Quackenbush was also reelected, but soon after was forced from office by scandal.)

"When Dick Riordan was endorsing and contributing nearly $500,000 to Tom Bradley's two campaigns for governor, I was supporting and working with George Deukmejian to implement strong Republican policies that benefited Californians," Jones continued. "I do consider Dick Riordan a friend of mine. But what works to make a good nonpartisan mayor of Los Angeles does not qualify him to represent the Republican Party as its nominee to challenge Gray Davis. Simply put, Dick Riordan does not have the track record as a Republican to represent the GOP and to beat Gray Davis."

Khachigian says Jones' attack will resonate with many GOP primary voters. "Dick Riordan's not a bad man. But his ecumenical politics would not fit as well in a statewide Republican election as it would as mayor of Los Angeles." While Khachigian acknowledges that conservatives are increasingly warming up to a Riordan candidacy, he says it would just gloss over the party's more deep-seated problems. "It'd be a good shortcut to getting credibility, quicker than doing it the hard way," he says.

Kevin Spillane, a GOP consultant who has worked for moderate Republicans and now heads the draft-Riordan effort, says Jones stands little chance of defeating Davis. "A conventional Republican candidate will have a tough time winning a statewide race in 2002," says Spillane. "Bill Jones criticized Riordan for being a moderate and an independent. But in California, those things are his strengths, not his weaknesses. He'll be able to attract other voters that the party has lost."

The quandary for the party, of course, is that a Riordan candidacy from the center might alienate the party's grass-roots base -- and its leadership -- on the right. The ideological war in the party has raged for the past decade, but as with Democrats 20 years ago, it seems that more and more California Republicans are willing to move to the center in order to win -- which is why conservatives like Reps. Rohrabacher and Dreier have endorsed Riordan.

Republican donors are also waiting for Riordan. The mayor's flirtation with a run has effectively frozen campaign donations to Jones, who must prove to the party faithful that he can raise the $50 million or more it will take to battle Davis. Jones has vowed to prove his fundraising mettle by raising $1 million by September. "Riordan's musing about the race has pretty much put the money on ice," said one Republican strategist. "This is the worst thing that can happen to Bill Jones." GOP candidate Simon, like Riordan, is independently wealthy and can finance his own campaign.

The question is whether Riordan can survive the primary. Spillane pointed to polling that shows Riordan ahead of both Jones and Simon. In a three-way race, according to the Field Poll, Riordan would lead by 40 over Jones, with 18, and Simon, with 6. And the Riordan bandwagon is only growing with Republicans, who want a winner above all else. "A lot of my conservative friends are behind it," says Khachigian of the Riordan candidacy. "I think they sense that, look, if we win the governor's office, we'll deal with the ideology later."

But for California Republicans, who seem increasingly out of step as the state takes a leap to the left, ideology is the problem, and the very reason Riordan is a viable statewide candidate.

A number of conservative and liberal Republicans point to the fall of communism as the root of the party's current problems. After the common enemy disappeared, the argument goes, internal tensions between the disparate factions of social conservatives and libertarians came to the forefront. Reagan was able to unite those groups through the force of his personality, using communism and big government as his foils. "Things that united the party don't exist anymore," says one GOP operative. "All of a sudden you've got social conservatives and country club social liberals, and they say, What have we got in common?"

Of course, it has been 12 years since the fall of the Berlin Wall, and the fact that the Republican Party is still blaming the end of communism for its troubles speaks to just how intractable those troubles are. Some of the same strains have been felt elsewhere in the country -- witness the defection of Sen. James Jeffords, I-Vt., and threats by Rhode Island Republican Sen. Lincoln Chafee to leave the party. But they have been felt perhaps most profoundly in California, home of two divergent Republican traditions -- that of Reagan and the independent, reformist streak of former California Gov. and U.S. Sen. Hiram Johnson -- who crusaded against the railroads and utilities, fought for worker protections and created California's initiative law.

Conservatives have found California to be increasingly hostile territory. The only Republican to win at the top of the ticket in the past 15 years was Pete Wilson. Like Riordan, Wilson was despised by many party faithful because he was a pro-choice moderate. Republicans even burned effigies of Wilson outside a state party convention in the early 1990s.

But unlike Riordan, Wilson was a strident crusader against affirmative action, illegal immigration and labor unions. In fact, his crusade against illegal immigrants is at least partially to blame for the state party's current woes. While he was more in sync with California voters on abortion and the environment than other Republicans, Wilson's focus on immigration during his 1994 reelection campaign -- and his embrace of Proposition 187, which would have denied social benefits to illegal immigrants -- was criticized as anti-Latino. While Wilson crushed Democrat Kathleen Brown, it was undeniably a Pyrrhic victory, galvanizing thousands of Latinos to register to vote, and vote Democratic.

Once upon a time, before 1994, Republicans saw the Latinization of California as good for the party. The conventional wisdom was that Republicans would be able to appeal to Latinos on social issues because most Latinos identify as Catholics and are sensitive to "family values." But in post-Wilson California, Latino voters have become a reliable Democratic bloc, voting about 4-1 Democratic. At the beginning of the 1990s, Latinos constituted about 7 percent of the state's voting population. Today, after the spurt of post-Proposition 187 registration, they make up about 15 percent of the state's voters.

Republicans are now looking to Riordan, as they looked to George W. Bush in 2000, to help their image with the state's Latino voters and moderate swing voters. Riordan was elected mayor in a solidly Democratic city with 43 percent of the Latino vote in 1993, and reelected with 60 percent Latino support in 1997, according to Los Angeles Times exit polls.

If Riordan runs, his main selling point in a Republican primary will be his electability. Implicit in his sales pitch is the fact that a social conservative like Jones can no longer win at the top of the ticket in California.

Khachigian refuses to declare the death of Reagan-style conservatism in California. "Would the state today be responsive to Reaganism? There are a lot of areas in which it would be," he says. "One would be lifting up the state economically, providing a new sense of hope for those left out of the economic growth. That was quintessential Reagan."

But since Reagan's departure, Californians have formed a consensus on many key social issues, such as the environment and abortion rights. Bush ran as a Reagan Republican last fall, and lost the state by 12 points.

Khachigian says the social libertarianism of Californians will be quickly shelved if the economy is still in the doldrums in November. "In 1998, when the economy is booming and chugging along, with the Dow comfortably over 10,000 and dot-commers making a pile of money, there's a lot of ability to focus on social issues," he says. "It's a lot different when the economy is having a lot of trouble. You can attack Reagan until the cows come home for abortion or the environment, but the economy was in the dumps [in 1980], so those things were overlooked. If Gray Davis had run in an economically depressed time, and if [1998 Republican gubernatorial nominee] Dan Lungren had run a better campaign, things would have been different."

Moderates in the party lay the blame on recalcitrant conservatives who have vocally pushed a socially conservative agenda and nominated conservative candidates. "The more, shall we say, 'enthusiastic' of members have taken over the party," says former Assemblyman Brooks Firestone of Santa Barbara, Calif., a moderate Republican who recently lost a bid to become party chairman. "These things go in cycles. Go back to the 1970s -- you couldn't run as a Democrat in favor of the death penalty. They wanted to eliminate it. Now they've stopped talking about it. I'm sure that Gray Davis is committed to ending the death penalty, but he's recognized that the people of California are committed to it. It will remain to be seen whether Republicans can do that with abortion. My efforts to tone down the rhetoric have not been successful."

For now, Republicans eager for Riordan to pick up Firestone's crusade will have to settle for "will he or won't he?" Khachigian doesn't think Riordan will make the plunge, but others are not so sure.

Riordan, an avid cyclist, recently canceled a bike trip to France, where he was to be part of Lance Armstrong's Tour de France support team. He said he had "a lot of thinking to do."

"As an avid cyclist myself, I can tell you, if he were to give up a summer bike trip in France for trips to Visalia and Eureka, that is significant," Firestone says. "That means something."

Shares