In 1942, a New Hampshire inventor named Earl Silas Tupper produced a bell-shaped, flexible, injection-molded polyethylene container that would quickly prove ideal for a multitude of kitchen uses. Tupperware had made its first appearance, and as soon as World War II ended and an era of American consumption could begin, the rest would be history. But what kind of history?

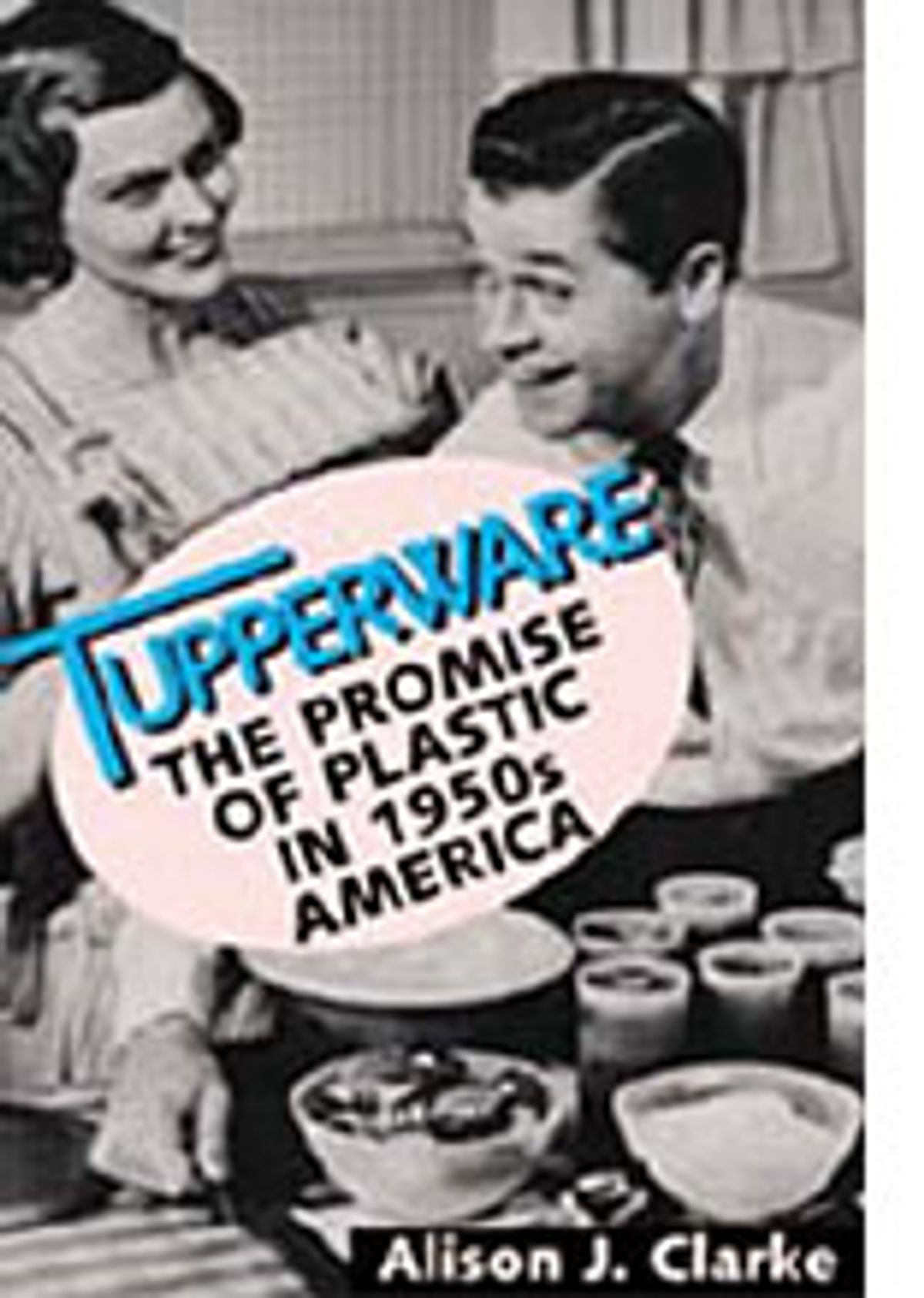

That's not at all a frivolous question. In "Tupperware: The Promise of Plastic in 1950s America," an entertaining study of the sociological and psychological significance of the phenomenon, Alison J. Clarke, a tutor in design history and material culture at the Royal College of Art in London, breaks new ground in our understanding of 1950s culture. She takes pains to debunk two commonly held scholarly interpretations of those ubiquitous plastic bowls and presents her own quite convincing neofeminist alternative. Tupperware, it turns out, makes an effective prism through which to view aspects of the cultural development of the nation in the latter portion of this century.

As Clarke points out, Tupperware couldn't possibly have achieved its place in American life without the Tupperware party, that oft-ridiculed but wildly successful suburban mainstay. The plastic containers, however attractive and functional they may have been, were languishing on the shelves until 1951, when Earl Tupper, in an act that, Clarke says, showed either "inspired entrepreneurial vision or a reflection of his desperation," handed over his entire sales effort to a neophyte named Brownie Wise.

Wise, an impoverished single mother from Detroit with little but a dream in her heart, was a true American original. She soon built a vast nationwide network of women dedicated to selling Tupper's products out of their homes. Her flamboyant style and the cult of personality she encouraged came into conflict with Tupper's austere New England ways. The clash ultimately got her fired; the "party plan" lives on to this day as Tupperware goes international.

Clarke rejects two academic views of the Tupperware phenomenon, one favorable and one critical. The positive one is that Tupperware became an American icon entirely because it was "a simple, uncluttered functional design, born of the modernist ethos 'Form Follows Function.'" Not so, Clarke argues: The Museum of Modern Art may have put Tupperware on exhibit in 1956, but American women wanted it in their refrigerators because it conveyed middle-class status, because it appealed simultaneously to frugality and ostentation and because their friends and neighbors were selling it and buying it.

The negative view is that the Tupperware party was a vapid, stifling, oppressive institution imposed upon passive American women by the forces of mass culture and advertising. Clarke strongly dissents: Actually, she says, Tupperware culture "offered an alternative to the patriarchal structures of conventional sales structures, which many women, completely alienated from the conventional workplace, wholeheartedly embraced." And Tupperware events permitted many women of the 1950s to gain their voices by speaking in public, thus developing the self-esteem they had lacked. Fostered by Brownie Wise's elaborate circles of reward for sales achievements, Tupperware's "self-help ethos countered alienation and fostered self-determination."

The 1950s are undergoing a reappraisal, with some scholars concluding that the drab black-and-

Shares