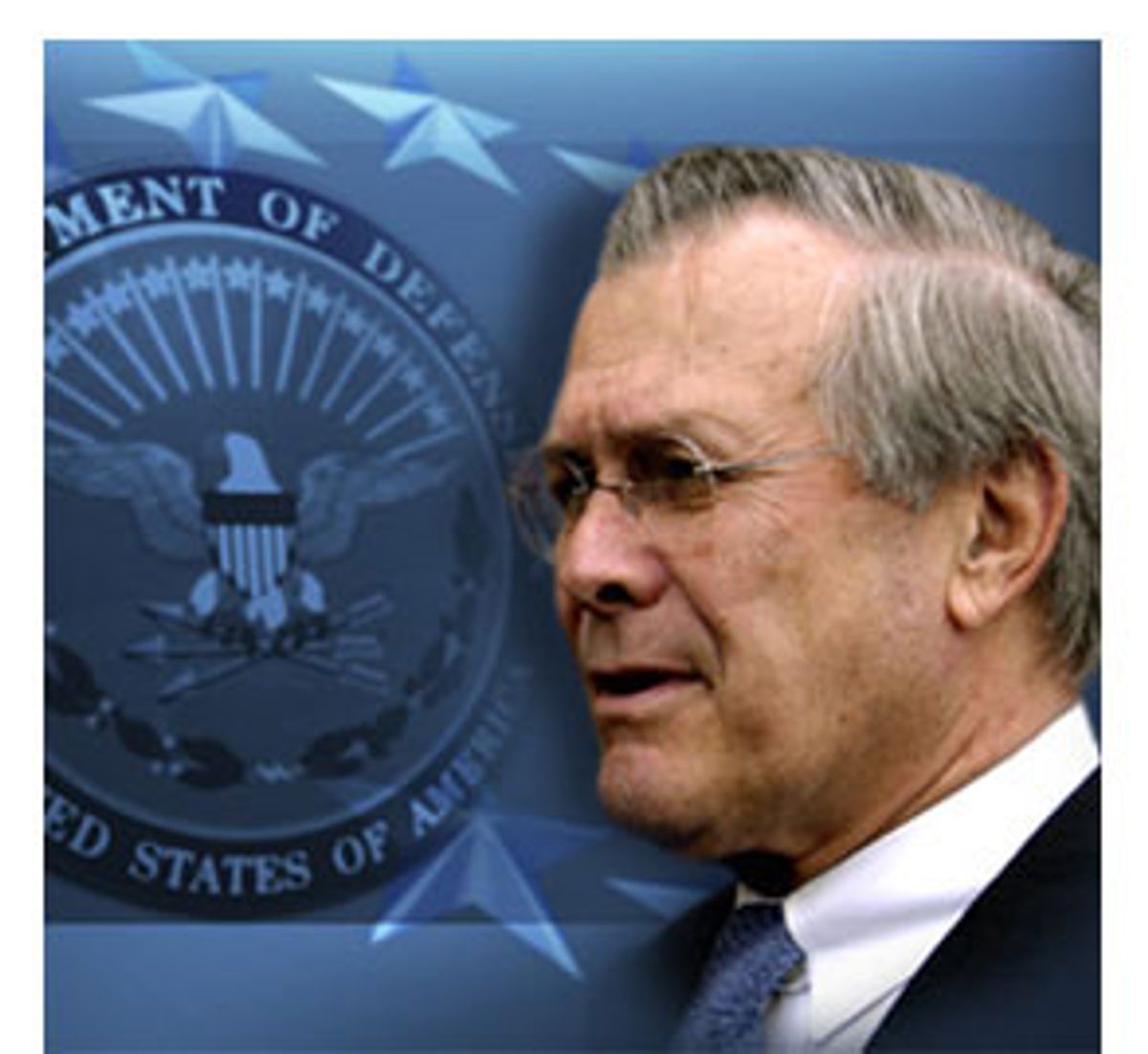

Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld told Bush in February of torture at Iraq's Abu Ghraib prison. From the dearth of detail Rumsfeld has recalled of that meeting one can deduce that Bush gave no orders, insisted on no responsibility, asked not to see the already commissioned Taguba report. If there are exculpatory facts, Rumsfeld has failed to mention them. If he received orders from the commander in chief, he neglected to implement them. One must presume Bush gave none. He acted as he did when he received the Aug. 6, 2001, presidential daily briefing titled "Bin Laden Determined to Strike in US" -- complacent and passive. Bush had asserted that the PDB required no action because it did not include exact times and places of attack; in the Taguba report, however, word about torture was highly specific.

The threat as Rumsfeld perceived it from the beginning was the news of torture itself. Suppressing it broadened into a defense at all costs of his position. For decades, Rumsfeld has gained a reputation, swimming in the bureaucratic seas, as a "great white shark" -- sleek, fast moving and voracious. As counselor to President Nixon during his impeachment crisis, his deputy was young Dick Cheney, who learned at his knee. Together they helped right the ship of state under President Ford, where they got a misleading gloss as moderates. Sheer competence at handling power was confused with pragmatism. Cheney became the most hard-line of congressmen, and Rumsfeld informed acquaintances that he was always more conservative than they may ever have imagined. One of the lessons the two appear to have learned from the Nixon debacle was ruthlessness. His collapse confirmed in them a belief in the imperial presidency based on executive secrecy. One gets the impression that they, unlike Nixon, would have burned the incriminating White House tapes.

Under President Bush, the team of Cheney and Rumsfeld spread across the top rungs of government, and staffed themselves with, members of the neoconservative cabal, infusing their right-wing temperaments with ideological imperatives. The unvarnished will to power was covered with the veneer of ideas and idealism. Invading Iraq was not a case of vengeance or mere power -- it was Rumsfeld, after all, who had traveled to Baghdad to lend U.S. support to Saddam Hussein in his war with Iran and help provide him with weapons of mass destruction -- but the cause of democracy and human rights.

On Rumsfeld's survival depends the fate of the neoconservative project. If he were to go, so would his deputy, the neoconservative Robespierre Paul Wolfowitz, and below him the cadres who stovepiped the disinformation that Iraqi exile and neoconservative darling Ahmed Chalabi used to manipulate public opinion before the war. It was Rumsfeld who argued immediately after Sept. 11 that Afghanistan was a steppingstone to Iraq, inserted his reliable man to write the National Intelligence Estimate that claimed WMD as the rationale for the war (suppressing contrary evidence) and dismissed Colin Powell's State Department's warnings about violent insurgency in the postwar period.

In his Senate testimony last week, Rumsfeld explained that the government asking the press not to report news of Abu Ghraib "is not against our principles. It is not suppression of the news." War is peace.

Six soldiers from a National Guard unit from West Virginia, who allegedly treated Abu Ghraib as a playpen of pornographic torture, have been designated as scapegoats. Will the show trials of these working-class antiheroes end inquiries about the chain of command? An extraordinary editorial published by the Army Times, which hasn't previously ventured into such controversy, said, "The folks in the Pentagon are talking about the wrong morons ... This was not just a failure of leadership at the local command level. This was a failure that ran straight to the top. Accountability here is essential -- even if that means relieving top leaders from duty in a time of war."

Retired Gen. William E. Odom, a former staff member of the National Security Council and now at the Hudson Institute, a conservative think tank, reflects the depth of dismay in the upper ranks of the military. "It was never in our interest to go into Iraq," he told me. He calls that war a "diversion" from the war on terrorism; the rationale for the war, finding WMD, "phony"; the U.S. Army overstretched, being driven "into the ground"; and the prospect of building a democracy in Iraq "zero." In Iraqi politics, he says, "legitimacy is going to be tied to expelling us. Wisdom in military affairs dictates withdrawal in this situation. 'We can't afford to fail' -- that's mindless. But the damage has been done. The issue is how we stop failing more. I'm arguing [for] a strategic decision."

One high-level military strategist told me that Rumseld is "detested" and that "if there's a sentiment in the Army, it is 'Support Our Troops, Impeach Rumsfeld.'"

The Council on Foreign Relations has been showing old movies with renewed relevance to its members. "The Battle of Algiers," which depicts the nature and costs of a struggle with terrorism, is the latest feature. The seething in the military against Bush and Rumsfeld might prompt a showing of "Seven Days in May," about a coup staged by a right-wing general against a weak liberal president, an artifact of the conservative hatred of President Kennedy in the early 1960s.

In 1992, Gen. Powell, chairman of the Joint Chiefs, awarded the prize for his Strategy Essay Competition at the National Defense University to Lt. Col. Charles J. Dunlap for "The Origins of the American Military Coup of 2012." His cautionary tale imagined an incapable civilian government creating a vacuum that draws a competent military into a coup disastrous for democracy. The military, of course, is bound to uphold the Constitution. But Dunlap wrote: "The catastrophe that occurred on our watch took place because we failed to speak out against policies we knew were wrong. It's too late for me to do any more. But it's not for you." "The Origins of the American Military Coup of 2012" is being circulated today among top U.S. military strategists.

Shares