Republicans representative of their permanent establishment have recently and quietly sent emissaries to President Bush, like diplomats to a foreign ruler isolated in his forbidden city, to probe whether he could be persuaded to become politically flexible. These ambassadors were not connected to the elder Bush or his closest associate, former National Security Advisor Brent Scowcroft, who was purged last year from the President's Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board and scorned by the current president. Scowcroft privately tells friends who ask whether he could somehow help that Bush would never turn to him for advice. So, in one case, a Republican wise man, a prominent lawyer in Washington who had served in the Reagan White House, sought no appointments or favors and was thought to be unthreatening to Bush, gained an audience with him. In a gentle tone, he explained that many presidents had difficult second terms, but that by adapting their approaches they ended successfully, as President Reagan had. Bush instantly replied with a vehement blast. He would not change. He would stay the course. He would not follow the polls. The Republican wise man tried again. Oh, no, he didn't mean anything about polls. But Bush fortified his wall of self-defensiveness and let fly with another heated riposte that he would not change.

He has been true to his word. On the sale of U.S. ports to a corporate entity owned by the United Arab Emirates, for example, he has been adamant. Congressional Republicans, observing Bush's spiraling decline in the polls, down this week to 34 percent in the New York Times/CBS News survey, and facing midterm elections in which they but not the president are on the ballot, are seized with sheer panic. In the House of Representatives, they already forced their majority leader, Tom DeLay, under indictment for illegal campaign funding, to quit his post. Then they bolted from supporting the lobbyist-larded Roy Blunt, his obvious successor, and selected John Boehner, less conspicuously tainted, to replace DeLay. At the first news of the port deal, both the House and Senate leaders hastily threw President Bush overboard. Now he has to apply presidential pressure on his own party's leaders to reel them back. While the Democrats act as a hectoring chorus, the real tension and play are between Bush and the terrified Republican Congress.

Bush's immovability was previously perceived as the determination of a man of simple but clear convictions. But as his policies have unfolded as disastrous, his image has been turned inside out. Instead of being perceived as secure, he is seen as out of touch; instead of being acknowledged as a colossus striding events, he is viewed as driftwood carried away by the flood.

Within the sanctum of the White House, his aides often handle him with flattery. They tell him that he is among the greatest presidents, that his difficulties are testimony to his greatness, that his refusal to change is also a sign of his greatness. The more is he flattered, the more he approves of the flatterer. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice has risen along with her current of flattery. She is expert at the handwritten little note extolling his historical radiance. Karen Hughes, now undersecretary of state for public diplomacy, was a pioneer of the flatterer's method. White House legal counsel Harriet Miers is also adept.

But it is Vice President Dick Cheney who has sought and gained the most through flattery. While Bush is constantly and lavishly complimented as supreme leader, Cheney runs the show. Through his chief of staff, David Addington, he controls most of the flow of information, especially on national security, that reaches the incurious president. Bush seeks no contrary information or independent sources. He does not delve into the recesses of government himself, as Presidents Kennedy and Clinton did. He never demands worst-case scenarios. Cheney and his team oversee the writing of key decision memos before Bush finally gets to check the box indicating approval.

Addington also dominates much of the bureaucracy through a network of conservative lawyers placed in key departments and agencies. The Justice Department regularly produces memos to justify the latest wrinkle in the doctrine of the "unitary executive," whether on domestic surveillance or torture. At the Defense Department, the counsel's office takes direction from Addington and acts at his behest to suppress dissent from the senior military on matters such as detainees or the "global war on terror."

Tightly regulated by Cheney and Bush's own aides (who live in fear of Cheney), the president hears what he wishes to hear. They also know what particular flattery he wants to receive, and they ensure that he receives it.

In "The Prince," Machiavelli highlighted the danger in his chapter titled "How Flatterers Must Be Shunned." He observed that "courts are full" of "this plague," and that it can be isolated only with difficulty. His solution was that the "prudent prince" must insist that his closest advisors never withhold the unvarnished facts from him. "Because," wrote Machiavelli, "there is no other way of guarding one's self against flattery than by letting men understand that they will not offend you by speaking the truth."

But when disturbing information manages to penetrate the carefully constructed net surrounding Bush, he instinctively rejects and condemns it. In July 2004, upon being briefed on the grim analysis of the growing Iraqi insurgency written by the CIA Baghdad station chief, Bush said, according to U.S. News & World Report, "What is he, some kind of defeatist?" Bush prefers to soak up the flattery. He responds only to praise of himself as the warrior-president at the battlements, fighting the enemies at the gates and the defeatists within.

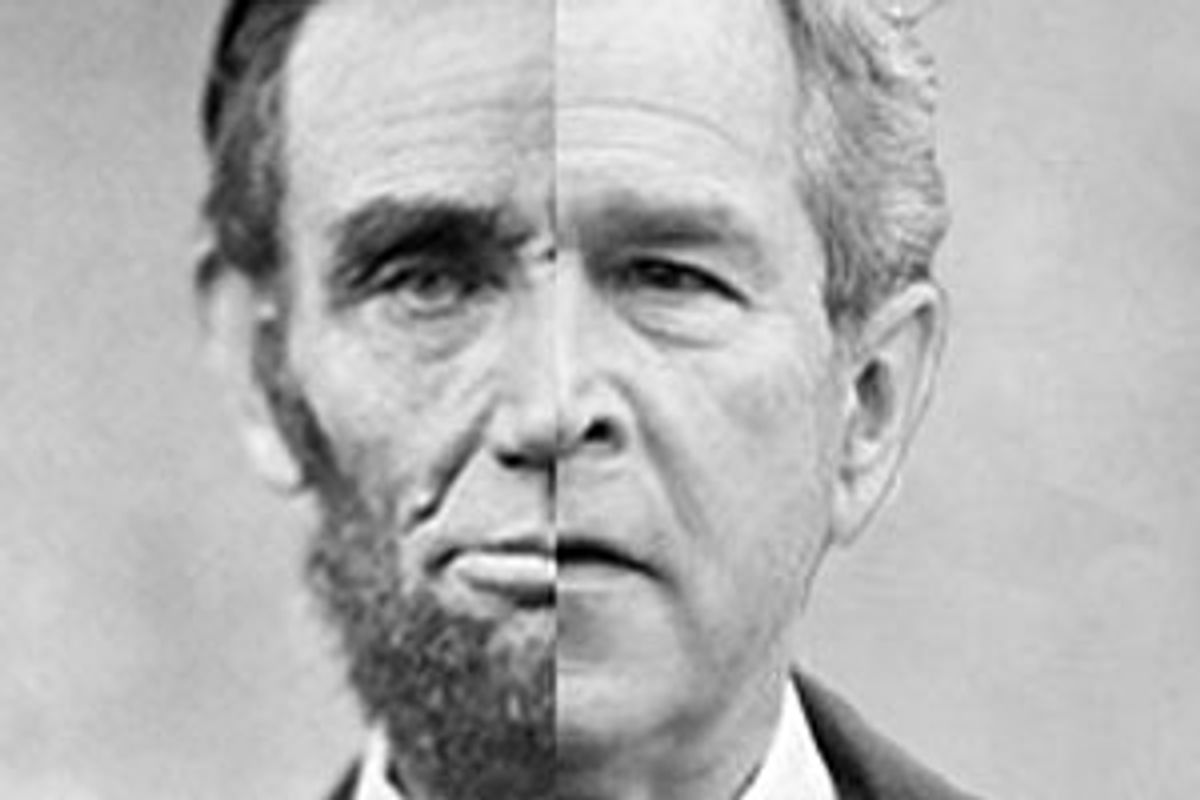

In the aftermath of the Iraq invasion, Bush was flattered by the analogy that he was like Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman, winning a world war and present at the creation of a new international order. However, since the election of 2004, a period during which the violence in Iraq has not diminished, Bush has been told he more closely resembles the beleaguered Abraham Lincoln. He is the Great Emancipator who has freed 50 million people in Afghanistan and Iraq but has not yet won the war. "It is courage that liberated more than 50 million people from tyranny," Bush declared on Veterans Day, Nov. 11, 2005. Enduring setbacks and suffering slings and arrows, he imagines himself enduring before inevitable and ultimate victory.

On May 11, 2005, Rice appeared on CNN's "Larry King Live" to say, "I've often wondered, in the darkest hours of the Civil War, what people were saying to Abraham Lincoln about whether this was going to turn out all right."

Just a month earlier, on April 20, Bush had dedicated the Abraham Lincoln Museum and Library in Springfield, Ill. Segueing seamlessly from the Civil War to the war on terror, from Gettysburg to Iraq, he conflated Lincoln's struggle and his own: "Our deepest values are also served when we take our part in freedom's advance -- when the chains of millions are broken and the captives are set free, because we are honored to serve the cause that gave us birth ... So we will stick to it; we will stand firmly by it."

This year, on Jan. 23, at Kansas State University, in one of a series of speeches he gave to explain once again his Iraq strategy, Bush digressed into a reverie about Lincoln's troubles. "I believe in what I'm doing," he said. "And I understand politics, and it can get rough. I read a lot of history, by the way, and Abraham Lincoln had it rough. I'm not comparing myself to Abraham Lincoln, nor should you think [so] just because I mentioned his name in the context of my presidency -- I would never do that. He was a great president. But, boy, they mistreated him. He did what he thought was right."

The greater Bush's difficulties, the more precipitously he falls in the polls, the more he is beseeched by anxious Republicans, and the harsher the realities, the tighter he clings to his self-image. Cheney and the others encourage his illusions, at least partly because the more intensely Bush embraces the heroic conception of himself, the more he resists change and the firmer their grip.

"It is an infallible rule," Machiavelli wrote in his chapter on flatterers, "that a prince who is not wise himself cannot be well advised, unless by chance he leaves himself entirely in the hands of one man who rules him in everything, and happens to be a very prudent man. In this case he may doubtless be well governed, but it would not last long, for that governor would in a short time deprive him of the state."

Shares