President Bush's first veto marks the first time he has lost control of the Republican Congress. But it is significant for more than that. Until now the president has felt no need to assert his executive power over the legislative branch. Congress was whipped into line to uphold his every wish and stifle nearly every dissent. Almost no oversight hearings were held. Investigations into the Bush administration's scandals were quashed. Potentially troublesome reports were twisted and distorted to smear critics and create scapegoats, like the Senate Select Intelligence Committee's report on faulty intelligence leading into the Iraq war. Legislation, which originates in the House of Representatives, was carefully filtered by imposition of an iron rule that it must always meet with the approval of the majority of the majority. By employing this standard, the Republican House leadership, acting as proxy for the White House, managed to rely on the right wing to dominate the entire congressional process.

The extraordinary power Bush has exercised is unprecedented. Bill Clinton issued 37 vetoes, George H.W. Bush 44, and Ronald Reagan 78. To be sure, they had to contend with Congresses led by the opposing party. Nonetheless, all presidents going back to the 1840s, and presidents before them, used the veto power, even when their parties were in the congressional majority. Just as the absence of any Bush vetoes has highlighted his absolute power, so his recourse to the veto signals its decline.

The vote in the Senate on Tuesday in favor of federal support for medical research using embryonic stem cells, which have the potential to cure many diseases and disabilities, while short of the two-thirds required to override a veto, was an overwhelming break with Bush, 63 to 37. The administration has struck back with false claims made by Karl Rove (assuming the role of science advisor) that adult stem cells are equivalent to embryonic ones, and with the accusation, made by White House press secretary Tony Snow, that using the thousands of routinely discarded embryos for research would amount to "murder." On Wednesday, Bush declared that the bill "crosses a moral boundary that our decent society needs to respect. So I vetoed it."

One-party congressional rule has been indispensable to Bush's imperial presidency. Its faltering reflects Republican panic in anticipation of the midterm elections, the disintegration of Bush's authority and of his concept of a radical presidency. As the consequences of Bush's rule bear down on the Republicans, the right demands that he recommit to the radicalism that has entangled him in one fiasco after another. Bush's latest crisis is also a crisis of the paranoid style that has been instrumental in sustaining Republican ascendancy.

The first principle underlying the Bush presidency was never more succinctly articulated than at the July 12 hearing called by the Senate Judiciary Committee. The Supreme Court had ruled two weeks earlier, in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, that the administration's detainee policy was in violation of the Geneva Conventions and without a legal basis. Steven Bradbury, the acting assistant attorney general in charge of the Office of Legal Counsel at the Department of Justice, appeared to defend not only the discredited policy but also the notion that as commander in chief Bush has the authority to make or enforce any law he wants -- the explicit basis of the infamous torture memo of 2002. Sen. Patrick Leahy, D-Vt., asked Bradbury about the president's bizarre claim that the Supreme Court's Hamdan decision in fact "upheld his position on Guantánamo."

"Was the president right or was he wrong?" asked Leahy. "It's under the law of war--," said Bradbury. Leahy repeated his question: "Was the president right or was he wrong?" Bradbury then delivered his immortal reply: "The president is always right."

Bradbury meant more than that Bush personally is "always right." He had condensed into a phrase the legal theory of presidential infallibility. In his capacity of commander in chief, the president can never be wrong, simply because he is president. Despite the Supreme Court's ruling in Hamdan that presidential powers in foreign policy do not override or supplant those that the Constitution assigns to Congress, Bradbury instinctively fell back on the central dogma of the Bush White House. According to the doctrine, the rule of law is just an expression of executive fiat. He can suspend due process of detainees, conduct domestic surveillance without warrants, and decide which laws and which parts of laws he will enforce by appending signing statements to legislation at will. The president becomes an elective monarch who should be above checks and balances.

On Tuesday, Attorney General Alberto Gonzales appeared before the Senate Judiciary Committee, where he reiterated his belief in presidential infallibility. Under questioning, he admitted that Bush himself had denied security clearances to the Justice Department's Office of Professional Responsibility, thereby thwarting its investigation into whether government lawyers had acted properly in approving and overseeing the National Security Agency's warrantless domestic surveillance, ordered by the president to evade the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court. Never before in its 31-year history has the OPR been denied clearances, much less through the direct intervention of the president. But Gonzales insisted that the president cannot do wrong. "The president of the United States makes decisions about who is ultimately given access," he said. And he is always right. Case closed.

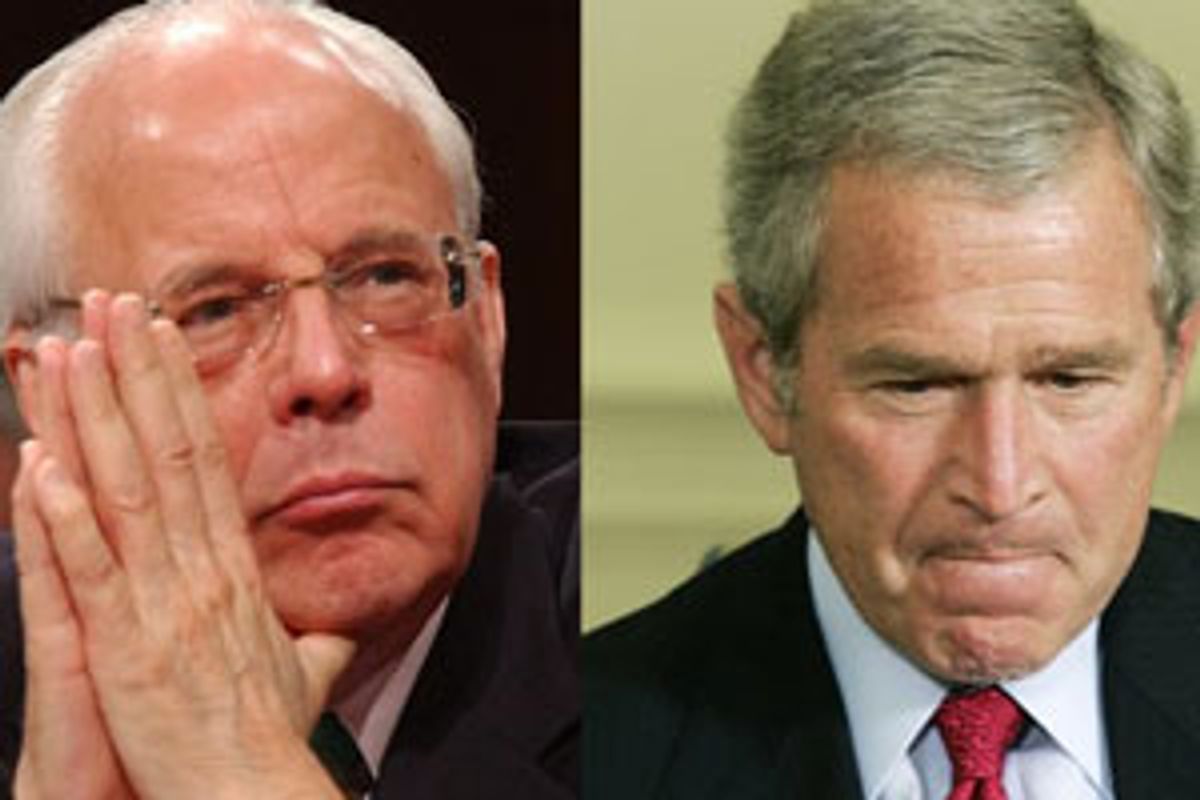

Bush's coverup, legitimate because he says it is, and Gonzales' defense, smug in his certitude, are only the latest wrinkles in his radical presidency. "The president and vice president, it appears," writes John W. Dean, the former counsel to President Nixon, in his new book, "Conservatives Without Conscience," "believe the lesson of Watergate was not to stay within the law, but rather not to get caught. And if you do get caught, claim that the president can do whatever he thinks necessary in the name of national security."

The metastasizing of conservatism under Bush is a problem that has naturally obsessed Dean. His part in the Watergate drama as the witness who stepped forward to describe a "cancer on the presidency" has given him an unparalleled insight into the roots of the current presidency's pathology. He recalls the words of Charles Colson, Nixon's counselor and overseer of dirty tricks: "I would do anything the president of the United States would ask me to do, period." This vow of unthinking obedience is a doctrinal forerunner of Bush's notion of presidential infallibility.

Dean, moreover, was close to Barry Goldwater, progenitor of the conservative movement and advocate of limited government. Dean was the high school roommate of Barry Goldwater Jr. and became close to his father. In his retirement, the senator from Arizona, who had been the Republican presidential nominee in 1964, had become increasingly upset at the direction of the Republican Party and the influence of the religious right. He and Dean talked about writing a book about the perverse evolution away from conservatism as he believed in it, but his illness and death prevented him from the task. Now, Dean has published "Conservatives Without Conscience," whose title is a riff on Goldwater's creedal "Conscience of a Conservative," and intended as an homage.

Conservatism, as Dean sees it, has been transformed into authoritarianism. In his book, he revives an analysis of the social psychology of the right that its ideologues spent decades trying to deflect and discourage. In 1950, Theodor Adorno and a team of social scientists published "The Authoritarian Personality," exploring the psychological underpinnings of those attracted to Nazi, fascist and right-wing movements. In the immediate aftermath of Sen. Joseph McCarthy's rise and fall, the leading American sociologists and historians of the time -- Daniel Bell, David Riesman, Nathan Glazer, Richard Hofstadter, Seymour Martin Lipset and others -- contributed in 1955 to "The New American Right," examining the status anxieties of reactionary populism. The 1964 Goldwater campaign provided grist for historian Hofstadter to offer his memorable description of the "paranoid style" of the "pseudo-conservative revolt."

While Dean honors Goldwater, he picks up where Hofstadter left off. "During the past half century," he writes, "our understanding of authoritarianism has been significantly refined and advanced." In particular, he cites the work of Bob Altemeyer, a social psychologist at the University of Manitoba, whose studies have plumbed the depths of those he calls "right-wing authoritarians." They are submissive toward authority, fundamentalist in orientation, dogmatic, socially isolated and insular, fearful of people different from themselves, hostile to minorities, uncritical toward dominating authority figures, prone to a constant sense of besiegement and panic, and punitive and self-righteous. Altemeyer estimates that between 20 and 25 percent of Americans might be categorized as right-wing authoritarians.

According to Dean's assessment, "Nixon, for all his faults, had more of a conscience than Bush and Cheney ... Our government has become largely authoritarian ... run by an array of authoritarian personalities," who flourish "because the growth of contemporary conservatism has generated countless millions of authoritarian followers, people who will not question such actions."

But it is Bush's own actions that have produced a political crisis for Republican one-party rule. In their campaign to retain Congress, Republicans are staking their chips on the fear generated by the war on terror and the culture war, doubling and tripling their bets on the paranoid style. To that end, House Republicans have unveiled what they call the "American Values Agenda." Despite the defeat of key parts of the program -- constitutional amendments against gay marriage and flag burning -- and the congressional approval of embryonic stem cell research, the Republicans hope that these expected setbacks will only inflame the conservative base. Their strategy is to remind their followers that enemies surround them and that the president is always right.

Shares