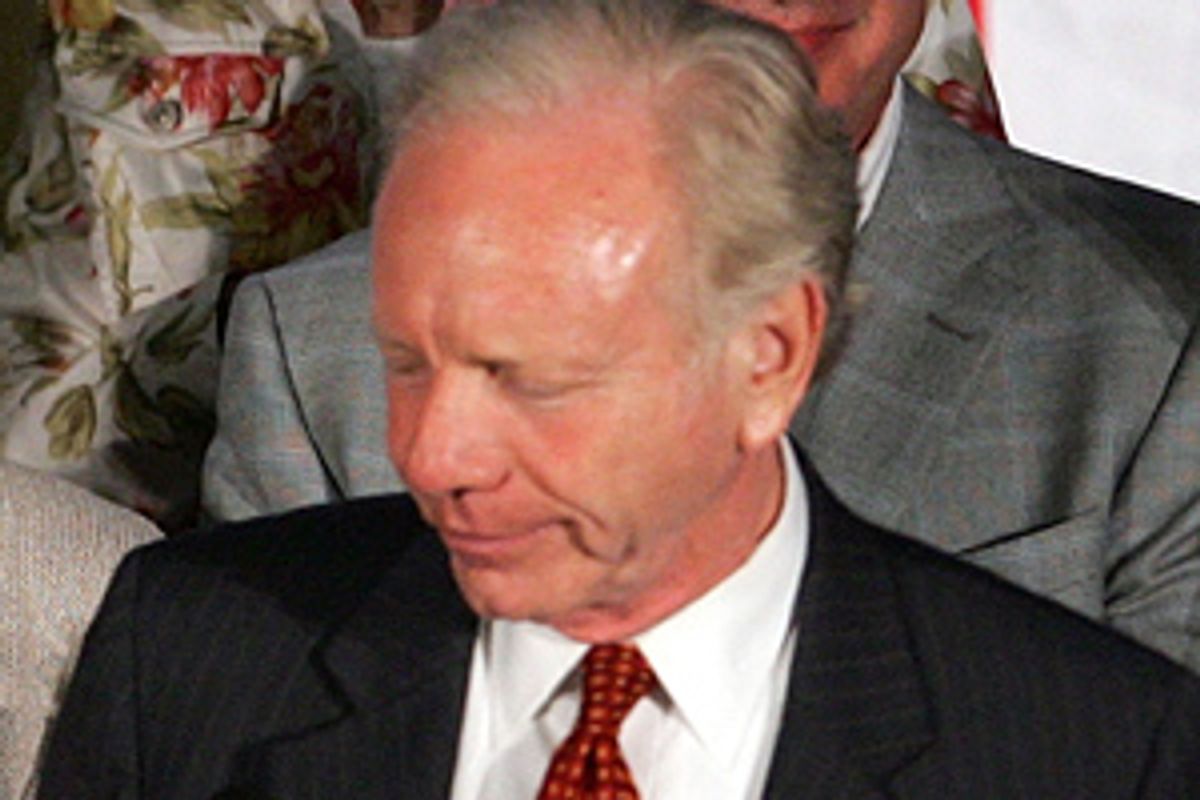

Joe Lieberman's fall from grace appears straightforward. In Connecticut, where George W. Bush and his war are intensely disliked, Lieberman stationed himself as the president's defender. But Lieberman's precipitous descent from nomination as vice president to rejection by his home state partisans is also something of a mystery.

Lieberman was once the most attractive and promising Democrat in his state, his grasp of political realities subtle and sinuous. But he became scornful of disagreement, parading himself as a moral paragon to whom voters should be privileged to pay deference. The elevation of his sanctimony was accompanied by the loss of his political sense.

When Lieberman ran his first primary campaign, for the state Senate, in 1970, against an entrenched Democratic machine politician, he was an insurgent reformer, relying on an army of young idealistic volunteers. (One of them was Yale law student Bill Clinton.) Lieberman was a star liberal on the Yale campus, editor of the Yale Daily News, a civil rights worker in the South, an activist against the Vietnam War, and yet adept at getting out the vote. His senior honors thesis was a study of the Democratic state boss, John Bailey, who forged competing ethnic groups into a winning coalition. The young Lieberman's victory seemed to herald a new day in Connecticut.

For decades, indeed for two centuries, Connecticut has been a caldron of peculiarly American culture wars. In the election of 1800, the president of Yale, speaking for the reigning puritan establishment, denounced the Democratic presidential candidate, Thomas Jefferson, as "immoral." Starting in the 1870s, Connecticut was straitjacketed by laws forbidding birth control. In 1926, Katharine Houghton Hepburn, the wife of a liberal Hartford doctor, formed the Connecticut Birth Control League to challenge the restriction. (Their daughter, actor Katharine Hepburn, continued their activism as the league grew into Planned Parenthood.)

In 1950, the state treasurer of Planned Parenthood, a liberal-minded Republican banker tainted by his association, was narrowly defeated in a race for the U.S. Senate. His name was Prescott Bush, father of George H.W. and grandfather of George W., and he won election two years later.

It was not until 1965 that the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Connecticut's birth control law was unconstitutional, violating the right to privacy, a decision that laid the groundwork for the legalization of abortion in 1973 and ignited new culture wars.

In 1988, conservatives in the state, led by right-wing writer William F. Buckley Jr., in their loathing for liberal Republican Sen. Lowell Weicker Jr., rallied behind his Democratic opponent, Joe Lieberman, who won a bare margin on the basis of their votes. Lieberman was liberal on abortion, but that didn't matter to the right, which was determined to purge the Republican Party.

Over time, Lieberman, an Orthodox Jew, became more observant and culturally conservative. His speech denouncing President Clinton as "immoral" during the impeachment spectacle was as unsurprising as it was unctuous. His links to neoconservatives and the religious right proliferated. He became close to Dick and Lynne Cheney and helped found a group with Lynne to criticize liberal professors. Last year, at the 50th anniversary dinner of Buckley's National Review, the leading conservative magazine, Lieberman sat at the head table.

Al Gore chose Lieberman as a symbol of his separation from Clinton, and it was symptomatic of the strategic misdirection that landed Gore in the Florida swamp. Lieberman's main contributions were an unusually gentle debate with Cheney and a unilateral concession to count illegal ballots in Florida that favored Bush.

In the rush to war in Iraq, Lieberman was in the forefront of cheerleading, and Bush took to citing him often. Entering the House chamber to deliver his 2005 State of the Union address, Bush famously kissed him, godfather-style. In November of last year, after a Potemkin village tour of Iraq, Lieberman wrote an Op-Ed in the Wall Street Journal hailing "the coming victory" and, a month later on the Senate floor, rebuked "Democrats who distrust President Bush" for failing to acknowledge "we undermine presidential credibility at our nation's peril."

Believing that he had turned into a sacrosanct institution beyond reproach, the acolyte of Democratic leader Bailey neglected political organization. Disdainful of New England Democrats for daring to criticize the Southern conservative president, Lieberman was stunned by the emergence of an intraparty opponent, Ned Lamont, a liberal patrician banker.

Lieberman finished his campaign on a desperate note, proclaiming his purity of heart as a Democrat and assailing Bush on Iraq blunders, even as he announced in losing that he would not abide by his party's verdict and instead run as an independent. The man of faith is now running on bad faith. Self-righteousness fostered self-delusion, leading to self-destruction. Lieberman's fall is a cautionary tale not limited to Connecticut.

Shares