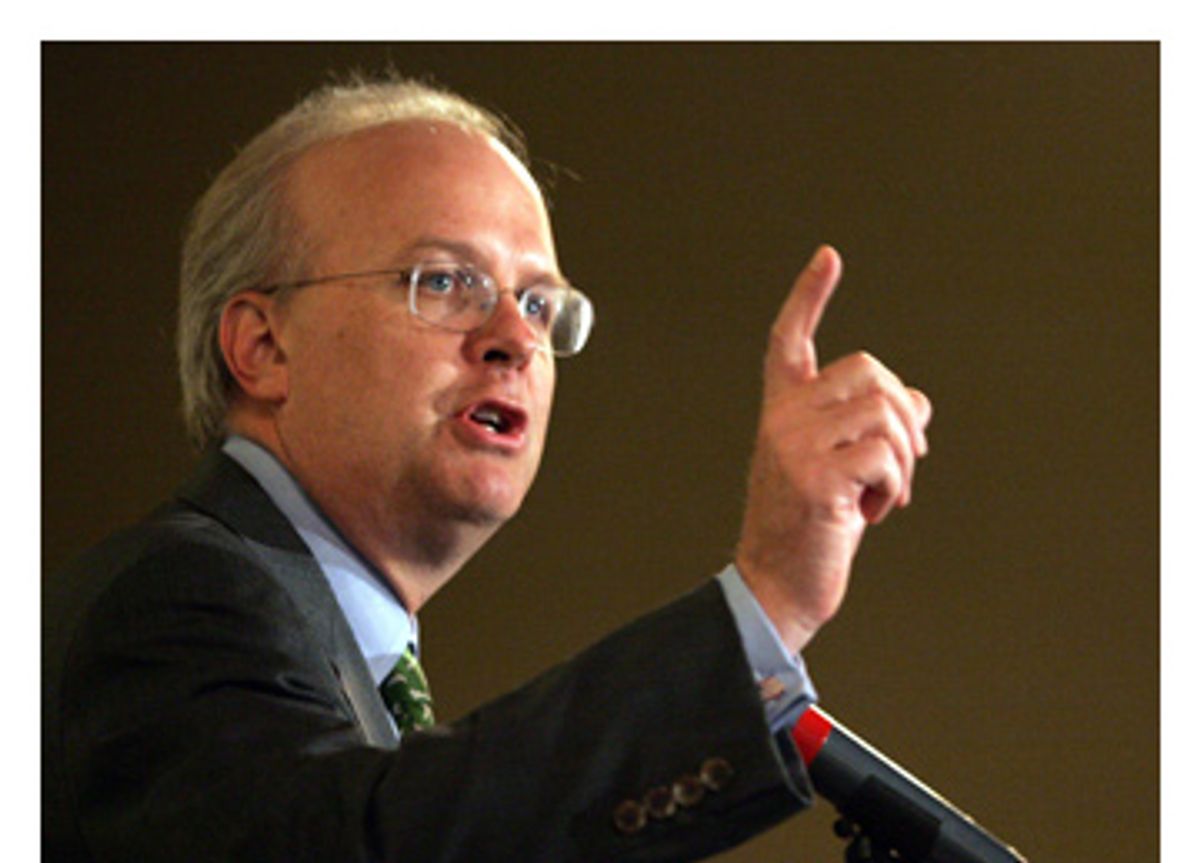

Karl Rove remains supremely confident, assuring fretful party leaders that Congress will continue to be under their control despite the stream of new polls revealing previously impregnable Republican incumbents suddenly vulnerable. "I believe Karl Rove," President Bush's chief of staff, Joshua Bolten, proclaimed in a faith-based confessional. While hardly any Republican candidates are running on the Bush record, many are airing TV commercials separating themselves from Bush, and few will even appear on a public platform with him, Republicans cling to Rove's Svengali-like reputation like a life raft. Only Rove stands between the president and the deep blue sea.

Now, however, it is apparent that Rove's short-term ploys have undermined long-term Republican possibilities. His tactical successes have laid the groundwork for strategic failure. His polarizing and paranoid politics have been an intrinsic aspect of Bush's consistently radical presidency, which may be checked and balanced for the first time with the election of the 110th Congress. Rove's legacy may be to leave Republicans with a regional Southern party whose constrictive conservatism fosters a solid Democratic North.

Rove's dismissal of the very notion of a political center was enabled by Sept. 11, which provided him with dramatic material to stigmatize the opposition as dangerously soft and to turbo-charge inflammatory social issues such as gay marriage. By defending hearth and home from enemies at the door and behind closed doors, Rove maximized turnout of the galvanized hardcore.

Yet Rove did not achieve his ambition of a grand realignment of American politics. In Bush's second term, Rove attempted to force privatization of Social Security, but Bush's plan never received even a single committee hearing in Congress. Hurricane Katrina exposed the corrupt political swamp of his government. And Iraq corroded the thin mandate Bush had left.

After having set the theme of the midterm elections campaign as "staying the course" in Iraq, Bush declared a week ago that he had never uttered the phrase he had used dozens of times. Nonetheless, on the stump, he follows the Rove script of politicizing terror, claiming that the opposition is unwilling to defend the country and is un-American. Speaking in the heavily Republican small towns where he is welcome to campaign, Bush turns torture and warrantless domestic surveillance into rhetorical points proving the Democrats' betrayal, whipping up crowds to shout, "Just say no." Bush: "When it comes to questioning terrorists, what's the Democrat answer?" "Just say no!" Bush: "Their approach comes down to this: The terrorists win and America loses!"

Though Bush has abandoned his "staying the course" slogan, Rove explains that the administration's Iraq war policy is clear and simple: "The real plan is this: Fight, beat 'em, win." His formulation, in the spirit of the cheerleading squad at the University of Utah, which he attended, is aimed less at the Shiite-dominated government of Iraq, recalcitrant about disbanding murderous militias, than at the disillusioned Republican base, especially white evangelicals, whose support in recent polls has fallen one-third from what it was in 2004.

Frantic Republicans are reduced to raising the specters of racial and sexual panic. In Tennessee, where Harold Ford Jr., an African-American, is running even with the Republican candidate, a Republican National Committee TV ad produced by a Rove protégé features a blonde vixen beckoning in a sultry voice, "Call me, Harold." In Virginia, former Reagan Secretary of the Navy turned Democratic candidate James Webb, who is also an acclaimed novelist, is being attacked for sexually explicit passages in his books written decades ago based on his experiences as a soldier in Vietnam. On these time-honored tactics in the South that inevitably alienate the North, the balance of power in the Senate rests.

It is conjectural but conceivable that had Bush governed after Sept. 11 as he had campaigned in 2000, as a "uniter, not a divider," he might have been able to forge a durable center-right consensus. That would have required appointing prominent Democrats to his Cabinet, reining in his power-mad vice president and secretary of defense, making moderate court nominations, and listening to the voices of skeptical realism on invading Iraq. Imagining this parallel universe underscores how Rove's victories helped pave the way to losing the potential for a lasting majority.

Few people foresaw the consequences of Bush's radicalism, perhaps least of all Bush himself. Last week, I was in Austin for the Texas Book Festival, where I met a woman who had encountered then Gov. Bush immediately after the Supreme Court handed down its decision in Bush v. Gore. "Can you believe I'm going to be the fucking president?" he said.

Shares