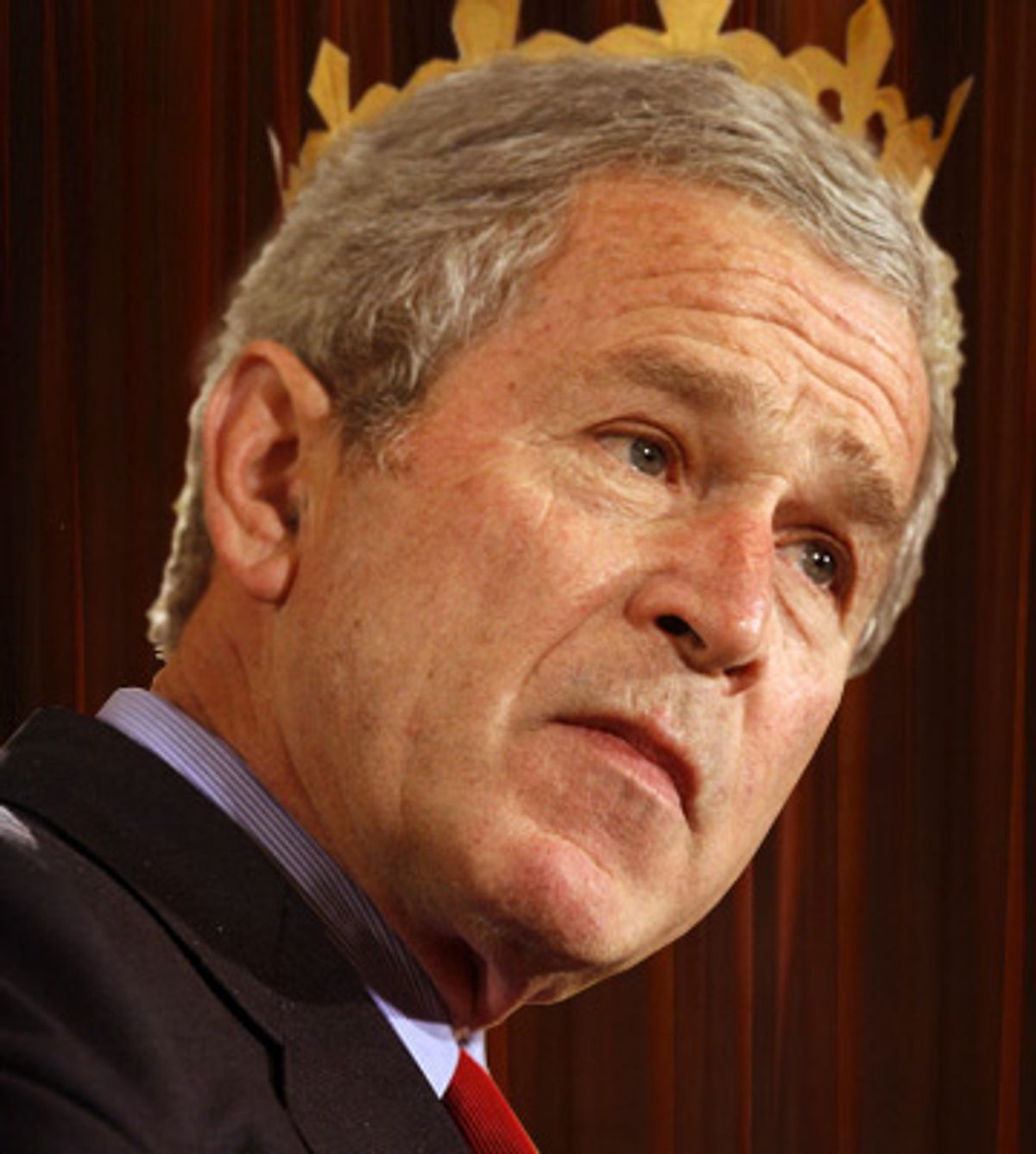

Loyalty has always been the alpha and omega of George W. Bush's presidency. But all the forms of allegiance that have bound together his administration -- political, ideological and personal -- are being shredded, leaving only blind loyalty. Bush has surrounded himself with loyalists, who fervently pledged their fealty, enforced the loyalty of others and sought to make loyal converts. Now Bush's long downfall is descending into a series of revenge tragedies in which the characters are helpless against the furies of their misplaced loyalties and betrayals. The stage is being strewn with hacked corpses -- on Monday, former Deputy Attorney General Paul McNulty; imminently, World Bank president Paul Wolfowitz; tomorrow, whoever remains trapped on the ghost ship of state. As the individual tragedies unfold, Bush's royal robes unravel.

Loyalty to Bush is the ultimate royal principle of the imperial presidency. The ruler must be unquestioned and those around him unquestioning. Allegiance to Bush's idea of himself as the "war president," "the decider" and "the commander guy" is paramount. But the notion that the ruler is loyal to those loyal to him is no longer necessarily true. While he must be beheld as the absolute incarnation of kingly virtue, his sense of obligation to those paying homage has become perilously relative.

Those who feel compelled to tell the truth rather than stick to the cover story are cast in the dust, like McNulty. Those Bush defends as an extension of his authority but who become too expensive become expendable, like Wolfowitz. And those who exist solely as Bush's creations and whose survival is crucial to his own are shielded, like Attorney General Alberto Gonzales.

On Tuesday, James Comey, the former deputy attorney general, disclosed a story that might have been written by Mario Puzo, and it explained the rise of Gonzales as attorney general. On March 10, 2004, Comey was serving as acting attorney general while John Ashcroft was in an intensive-care unit being treated for pancreatitis. After an "extensive review" by the Justice Department's Office of Legal Counsel, which concluded that Bush's warrantless domestic surveillance program was illegal, Comey refused to sign its reauthorization. An aide to Ashcroft tipped Comey off that White House legal counsel Gonzales and chief of staff Andrew Card were headed to Ashcroft's hospital to get him to sign it. Comey rushed to the darkened room, where he briefed the barely conscious Ashcroft. Gonzales and Card entered minutes later, demanding that Ashcroft comply. He refused, pointing to Comey, saying he was the attorney general. "I was angry. I had just witnessed an effort to take advantage of a very sick man," Comey testified.

Gonzales and Card then summoned Comey to the White House, where they attempted to intimidate him by telling him that Vice President Dick Cheney and his counsel, David Addington, were in favor of the reauthorization. Comey still refused. And the program went forward without the legal Justice Department approval. Comey and other high Justice Department officials prepared their resignation letters. The next day, having heard about the planned mass resignations, President Bush met alone with Comey, who briefed him on what needed to be done to bring the program under the law. Several weeks later Comey signed the authorization for a legal program. But during that period it was conducted outside the law.

Then, after Bush's reelection, Ashcroft was not reappointed. In his place Bush sent a new name to the Senate for confirmation -- Alberto Gonzales. Every position he had held was the result of his undying loyalty to Bush. The confrontation in Ashcroft's hospital room had been a turning point in his rise. Comey, who Bush privately derided as "Cuomo," quit. In his confirmation hearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee, Gonzales was asked about domestic surveillance, and he blithely misled the senators, acting as if he would always uphold the existing law, even though he had pressured Ashcroft and Comey to approve the illegal program. "The government cannot do that without first going to a judge," he said. "Government goes to the FISA [Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act] court and obtains a warrant to do that." Gonzales spoke those lines knowing he had done precisely the opposite. His lie demonstrated his higher loyalty to his patron.

At the moment that Comey was finishing his testimony about the drama at Ashcroft's sickbed, Gonzales was delivering a speech at the National Press Club blaming his former deputy for the political purge of eight U.S. Attorneys. "You have to remember," said Gonzales, "at the end of the day, the recommendations reflected the views of the deputy attorney general. The deputy attorney general would know best about the qualifications and the experiences of the United States attorneys community, and he signed off on the names." Gonzales had previously accepted generic "responsibility," claimed he didn't know anything about the dismissals and also blamed his former chief of staff, D. Kyle Sampson.

McNulty had, in fact, testified truthfully before the Senate, which reportedly infuriated Gonzales. Though ostensibly in charge of the U.S. attorneys, McNulty was kept out of the loop of the detailed planning for the purge, informed only in outline and briefed to give false testimony about the reasons for the firings by Sampson and others at his February appearance before the Senate Judiciary Committee. After McNulty conveyed his talking points about the U.S. attorneys being dismissed for "performance related" problems, he conceded under questioning that one had been replaced in order to fill his post with one of Karl Rove's protégés. That revelation blew up the scandal. McNulty's scapegoating and resignation were inevitable.

McNulty was tainted as a betrayer for telling the truth. He had been an operator for two decades within the Republican Party, but his loyal service could not protect him. A graduate of the Capital University Law School in Columbus, Ohio, he had striven upward as a faithful party man, making a career of political networking. His adherence to the principles of the Federalist Society lent him an imprimatur as a reliable conservative. He served as counsel to the House Judiciary Committee during the impeachment of President Clinton. His partisanship was considered so solid that he was named head of the Bush transition team for the Justice Department. He received the plum appointment as U.S. attorney for Northern Virginia, the so-called rocket docket, used for high-profile terrorism cases after 9/11, like that of John Walker Lindh. With Comey's departure, he rose to deputy attorney general.

In the end, McNulty suffered Comey's fate. His loyalty to party did not extend beyond the boundaries of the law. Thus he became a betrayer and a fall guy. His reputation was tarnished while Gonzales remained. Gonzales carried out his shameless finger-pointing at McNulty without the slightest hesitation. The destruction of trust within his department seemed to bother him not at all. His instinct for self-preservation easily triumphed over his desire for self-respect. Bush's loyalty to Gonzales is a monument to his vulnerability if he were to resign.

Monica Goodling, the former No. 3 ranking Justice Department official, presents another version of loyalty, that of the religious fanatic. Her refusal to testify before the Senate, invoking the Fifth Amendment, was brushed aside last week by a federal court that granted her limited immunity. Her equation of loyalty is to faith, a complete commitment in which her political agenda is part of a destined plan for salvation. Goodling sees Bush as the crusader king and herself as loyal vassal. Within this administration, she is not deluded, and her rise without visible credentials was proof that she was well prepared by Pat Robertson's Regent University to serve Bush as the Lord Ruler.

As Gonzales maintained his grip on his office while his deputy and aides were tossed into the inferno, the Wolfowitz drama inexorably moved to its final act. Wolfowitz, intellectual architect of the Iraq war as deputy secretary of defense, and even before, had had a long career before receiving Bush's patronage. Bush, indeed, is not his patron, but Cheney, for whom Wolfowitz was an aide when Cheney was secretary of defense in the elder Bush's administration, is. Wolfowitz's career precedes that period, too, as one of the most fully formed neoconservatives in Washington. Unlike Gonzales, he is not Bush's creature. But Bush's policy is his. In being loyal to Wolfowitz, Bush is tacitly acknowledging his debt, not his majesty. He should feel compelled to defend Wolfowitz not because he is his appointee as president of the World Bank, but because Wolfowitz formulated the central purpose of the Bush presidency in the invasion of Iraq.

In his loyalty to his own ideas, Wolfowitz exhibits his loyalty to the man of ideas -- himself. From abstraction to abstraction, he has bullied his cause and career forward. His loyalty to Bush is contingent on Bush's embrace of Wolfowitz's schemes. Wolfowitz has never shown allegiance to the institutions where he served: not to the Defense Department, which was an instrument for his notions, nor to the World Bank. He surrounded himself with ill-qualified ideological aides, whose loyalty was above all to him and through him to his ideas. The professional staffs at both the Pentagon and the World Bank seethed at Wolfowitz's highhanded managerial style, a combination of arrogance and incompetence.

At the World Bank, he entangled himself in a scandal involving his girlfriend, Shaha Riza, personally arranging for the bank to pay her a large salary increase to move her to a State Department foundation, then blaming the bank's staff for having approved the decision. According to the World Bank report issued this week, Wolfowitz muttered a malediction to the head of the bank's human resources department: "If they fuck with me or Shaha, I have enough on them to fuck them too." Thus Wolfowitz posed as Tony Soprano and depicted the World Bank as the Bada Bing. Loyalty would be forthcoming, or else.

The report described Wolfowitz as a person of "questionable judgment and a preoccupation with self-interest" who "saw himself as the outsider to whom the established rules and standards did not apply." His insistence that he had been requested by the bank to arrange Riza's job "simply turns logic on its head."

On Tuesday, Wolfowitz defended himself by blaming his girlfriend, saying of the bank staff, "Its members did not want to deal with a very angry Ms. Riza." He added that her "intractable position" forced him to give her a large salary increase. With that, the honorable gentleman attributed his rule breaking to his emotionally volatile girlfriend. In short, the bitch set him up.

In a final letter of defense, Wolfowitz pleaded that he was the victim of "unfair" treatment, that he was maligned as being described as a "boyfriend" and that Riza was also denigrated as a "girlfriend." He reminded the bank board of his dear children.

Meanwhile, Cheney, demonstrating his loyalty, called Wolfowitz "a very good president of the World Bank," adding, "I hope he will be able to continue." As part of the salvage effort, Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson, the former chief of Goldman Sachs, was enlisted to telephone finance ministers to urge them to support keeping Wolfowitz. A recent appointee, with no history of involvement with Wolfowitz, Paulson lent his reputation to the scandal-ridden neocon as an act of loyalty to the administration as though it were just a business matter. He simply nicked him as part of the damage. Paulson, too, was left out to dry when White House press secretary Tony Snow announced that insofar as Wolfowitz's future was concerned "all options are open," a formula applied also to Iran.

The root of "loyal" is loi, or French for law. Under Bush, loyalty has become a law unto itself. Bush is loyal to those who break the rules but adhere to him. Avowing loyalty for the administration becomes a substitute for making difficult ethical and moral decisions. Yet the less Bush and his loyalists are willing to engage the harsh realities they have created, the more comfort they draw from loyalty. Once loyalty is no longer reciprocal, as in the McNulty case, the leader becomes more isolated as those beneath him become increasingly insecure and paranoid about their status. Demonstrations of loyalty cease being effective as displays of power and greatness. Instead, they are seen as stonewalling or sandbagging, more like the levees of New Orleans that will be inevitably breached. Loyalty to Bush has become loyalty to his self-image and, in the case of Gonzales, loyalty above the law, betraying the meaning of the word itself.

Shares