There has never been a moment when we were not winning in Iraq. Victory has followed victory, from "Mission Accomplished" to the purple fingers of the Iraqi election to, most recently, President Bush's meeting at Camp Cupcake in Anbar province with Abdul-Sattar Abu Risha, the Sunni leader of the group Anbar Awakening (who was assassinated a week later). Turning point has followed turning point, from Bush's proclamation two years ago of his "National Strategy for Victory in Iraq" to his announcement last week of his "Return on Success." "We're kicking ass," he briefed the Australian deputy prime minister on Sept. 6 about his latest visit to Iraq. In his quasi-farewell address to the nation on Sept. 13, Bush assigned any possible shortcomings to Gen. David Petraeus and bequeathed his policy "beyond my presidency" to his successor.

After Bush pretended to deliberate over whether he would agree to his own policy as presented by his general in well-rehearsed performances before Congress -- "President Bush Accepts Recommendations" read a headline on the White House Web site -- he established an ideal division of responsibility. Bush could claim credit for the "Return on Success," whenever that might be, while Petraeus would be charged with whatever might go wrong.

One week after Petraeus flashed his metrics, a whole new set of facts on the ground suddenly emerged: an admission (previously denied) by Petraeus that the United States was arming the Sunnis, who might use those weapons in the next phase of Iraq's civil war; the release of a Pentagon report that there is "an increase in intra-Shi'a violence throughout the South" (a report conveniently withheld as Petraeus was testifying); the Iraqi government's expulsion of Blackwater, a private security firm with close ties to the administration, after a band of its guards gunned down Iraqi civilians; the restriction of all nonmilitary U.S. personnel in Iraq to the Green Zone; a report by the Iraqi Red Crescent that about 1 million people are internal refugees as a result of ethnic cleansing (apart from the more than 2 million refugees who have fled the country); and the announcement by the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform of an investigation into the State Department's inspector general for quashing scrutiny and embarrassing studies of fraud in the construction of the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad, among other projects.

As these events played out, Petraeus was detailed as Bush's Willy Loman to preside over the cooling of the special relationship with America's most important ally in the coalition of the willing. The general traveled to London to meet with Prime Minister Gordon Brown on the policy from which he is rapidly disengaging, already having withdrawn British forces in Basra to its airport before final evacuation. Such is the face of victory 10 days after Petraeus' march through Capitol Hill.

In his semiretirement, Bush engaged in appeals to history, which he now says on nearly every occasion will absolve him. Early on and riding high, he expressed contempt for history. "History, we'll all be dead," he sneered to Bob Woodward in an interview for "Bush at War," a panegyric to Bush the triumphant after the Afghanistan invasion and before Iraq. Now Bush cites history as justification for everything he does. "You can't possibly figure out the history of the Bush presidency -- until I'm dead," he told Robert Draper, his authorized biographer, in an interview for "Dead Certain." The use of the words "history" and "dead" between the Woodward and Draper interviews makes for a world of difference -- the difference between a president who couldn't care less and one who cares desperately but can't admit it.

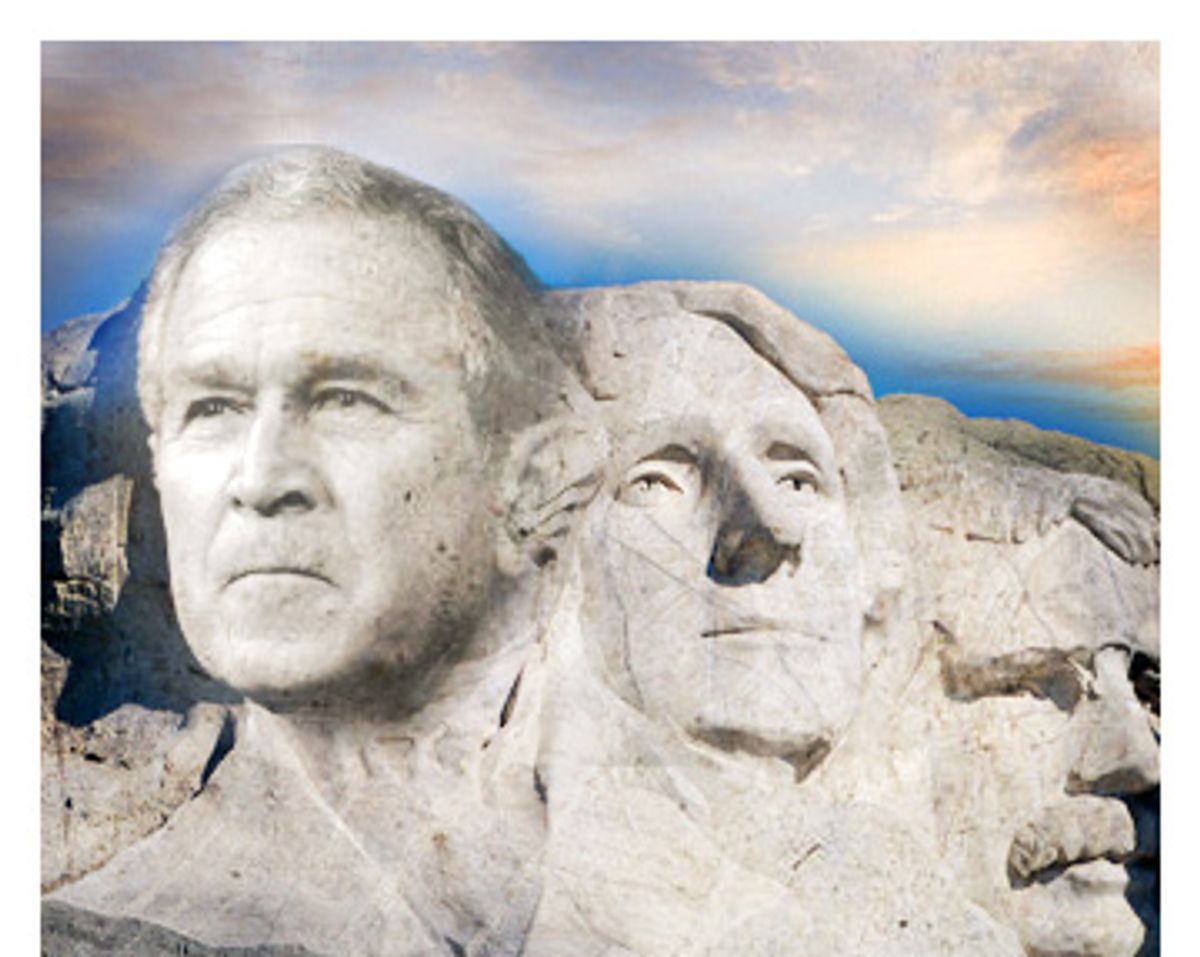

Bush incessantly invokes a host of presidents past -- Truman, Lincoln and Washington -- as appropriate comparisons, and also talks of Winston Churchill. Frederick Kagan, the neoconservative instigator of "the surge," refers to it as "Gettysburg," a leap of historical imagination that transforms Bush into the Great Emancipator. In his unstoppable commentary about himself, Bush has become as certain of his exalted place in history as he is of his policy's rightness. He projects his image into the future, willing his enshrinement as a great president. History has become a magical incantation for him, a kind of prayerful refuge where he is safe from having to think in the present. For Bush, history is supernatural, a deus ex machina, nothing less than a kind of divine intervention enabling him to enter presidential Valhalla. Through his fantasy about history as afterlife -- the stairway to paradise -- he rationalizes his current course.

Draper's biography has the feel of a lengthy feature magazine article wrapped in a dust jacket. It lacks any serious discussion of the influence of Dick Cheney, the rise of the neoconservatives, Karl Rove's attempt to create a one-party state, the government's torture policy, splits within the senior military, the scapegoating of the CIA, or the evisceration of federal departments and agencies. Nonetheless, Draper's unusual access enabled him to collect valuable anecdotes as well as to put a microphone in front of a president who, when interrupted by an aide, told him not to worry because the interview was "worthless." Letting down his guard, Bush does not understand what he reveals.

In his interviews with Draper, he is constantly worried about weakness and passivity. "If you're weak internally? This job will run you all over town." He fears being controlled and talks about it relentlessly, feeling he's being watched. "And part of being a leader is: people watch you." He casts his anxiety as a matter of self-discipline. "I don't think I'd be sitting here if not for the discipline ... And they look at me -- they want to know whether I've got the resolution necessary to see this through. And I do. I believe -- I know we'll succeed." He is sensitive about asserting his supremacy over others, but especially his father. "He knows as an ex-president, he doesn't have nearly the amount of knowledge I've got on current things," he told Draper.

Bush is a classic insecure authoritarian who imposes humiliating tests of obedience on others in order to prove his superiority and their inferiority. In 1999, according to Draper, at a meeting of economic experts at the Texas governor's mansion, Bush interrupted Rove when he joined in the discussion, saying, "Karl, hang up my jacket." In front of other aides, Bush joked repeatedly that he would fire Rove. (Laura Bush's attitude toward Rove was pointedly disdainful. She nicknamed him "Pigpen," for wallowing in dirty politics. He was staff, not family -- certainly not people like them.)

Bush's deployed his fetish for punctuality as a punitive weapon. When Colin Powell was several minutes late to a Cabinet meeting, Bush ordered that the door to the Cabinet Room be locked. Aides have been fearful of raising problems with him. In his 2004 debates with Sen. John Kerry, no one felt comfortable or confident enough to discuss with Bush the importance of his personal demeanor. Doing poorly in his first debate, he turned his anger on his communications director, Dan Bartlett, for showing him a tape afterward. When his trusted old public relations handler, Karen Hughes, tried gently to tell him, "You looked mad," he shot back, "I wasn't mad! Tell them that!"

At a political strategy meeting in May 2004, when Matthew Dowd and Rove explained to him that he was not likely to win in a Reagan-like landslide, as Bush had imagined, he lashed out at Rove: "KARL!" Rove, according to Draper, was Bush's "favorite punching bag," and the president often threw futile and meaningless questions at him, and shouted, "You don't know what the hell you're talking about."

Those around him have learned how to manipulate him through the art of flattery. Former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld played Bush like a Stradivarius, exploiting his grandiosity. "Rumsfeld would later tell his lieutenants that if you wanted the president's support for an initiative, it was always best to frame it as a 'Big New Thing.'" Other aides played on Bush's self-conception as "the Decider." "To sell him on an idea," writes Draper, "aides were now learning, the best approach was to tell the president, This is going to be a really tough decision." But flattery always requires deference. Every morning, Josh Bolten, the chief of staff, greets Bush with the same words: "Thank you for the privilege of serving today."

Draper reports a telling exchange between Bush and James Baker, one of his father's closest associates, the elder Bush's former secretary of state and the one the family called on to take command of the campaign for the 2000 Florida contest when everything hung in the balance. Baker's ruthless field marshaling safely brought the younger Bush into the White House. Counseling him in the aftermath, Baker warned him about Rumsfeld. "All I'm going to say to you is, you know what he did to your daddy," he said.

Indeed, Rumsfeld and the elder Bush were bitter rivals. Rumsfeld had scorn for him, and tried to sideline and eliminate him during the Ford administration because he wanted to become president himself. If George W. Bush didn't know about it before, he knew about it then from Baker, and soon thereafter he appointed Rumsfeld secretary of defense. Draper does not reflect on this revelation, but it is highly suggestive.

Quoted in an Aug. 9 article in the New York Times on the lachrymose father, Andrew Card, aide to both men, lately as White House chief of staff, and a family loyalist, spoke out of school. "It was relatively easy for me to read the sitting president's body language after he had talked to his mother or father," Card said. "Sometimes he'd ask me a probing question. And I'd think, Hmm, I don't think that question came from him."

The elder Bush assumed that the Bush family trust and its trustees -- James Baker, Brent Scowcroft and Prince Bandar -- would take the erstwhile wastrel and guide him on the path of wisdom. In this conception, the country was not entrusted to the younger Bush's care so much as Bush was entrusted to the care of the trustees. He was the beneficiary of the trust. But to the surprise of those trustees, he slipped the bonds of the trust and cut off the family trustees. They knew he was ill-prepared and ignorant, but they never expected him to be assertive. They wrongly assumed that Cheney would act for them as a trustee.

Cheney had worked with and for them for decades and seemed to agree with them, if not on every detail then on the more important matter of attitude, particularly the question of who should govern. The elder Bush had helped arrange for Cheney to become the CEO of Halliburton, making him a very rich man at last. But Bush, Baker, Scowcroft et al. didn't realize that Cheney's apparent concurrence was to advance himself and his views, which were not theirs. When absolute power was conferred on him, the habits of deference lapsed, no longer necessary. ("Thank you for the privilege of serving today.") Cheney was always more Rumsfeld oriented than Bush oriented. The elder Bush knew that Rumsfeld despised him and that Cheney was close to Rumsfeld, just as he knew his son's grievous limitations. But the obvious didn't occur to him -- that Cheney would seize control of the lax son for his own purposes. The elder Bush committed a monumental error, empowering a regent to the prince who would betray the father. The myopia of the old WASP aristocracy allowed him to see Cheney as a member of his club. Cheney, for his part, was extremely convincing in playing possum. The elder Bush has many reasons for self-reproach, but perhaps none greater than being outsmarted by a courtier he thought was his trustee.

Through his interposition of Petraeus, Bush has bound his party to his fate. Of the Republicans, only Newt Gingrich, former speaker of the House, leader of the 1994 self-styled radical "revolution" that captured Congress, is willing to speak publicly about the danger Bush poses to the future of the party. "I believe for any Republican to win in 2008, they have to have a clean break and offer a dramatic, bold change," he told a group of reporters on Sept. 14. "If we nominate somebody who has not done that ... they're very, very unlikely to win it."

But repudiating Bush would also mean repudiating Gingrich's legacy, too. Draper reports that Bush loves claiming Ronald Reagan, not his father, as his role model. But Gingrich, more than Reagan, is Bush's forerunner. It was Gingrich who heightened the politics of polarization to a level of personal attack and unscrupulousness unlike any seen since the underside of Richard Nixon's operations was exposed in the Watergate scandal. Reagan was free of such dishonest and vicious politics. Bush, Cheney and Rove ("Pigpen") picked up where Gingrich left off. Republicans can no more return to the halcyon days of Reagan than magic carpets can be used in Iraq. For the Republicans to recover, they would have to extirpate their entire recent history, root and branch.

"History would acquit him, too. Bush was confident of that, and of something else as well," writes Draper. "Though it was not the sort of thing one could say publicly anymore, the president still believed that Saddam had possessed weapons of mass destruction. He repeated this conviction to Andy Card all the way up until Card's departure in April 2006, almost exactly three years after the Coalition had begun its fruitless search for WMDs."

Bush grasps at the straws of his own disinformation as he casts himself deeper into the abyss. The more profound and compounded his blunders, and the more he redoubles his certainty in ultimate victory, the greater his indifference to failure. He has entered a phase of decadent perversity, where he accelerates his errors to vindicate his folly. As the sands of time run down, he has decided that no matter what he does, history will finally judge him as heroic.

The greater the chaos, the more he reinforces and rigidifies his views. The more havoc he wreaks, the more he insists he is succeeding. His intensified struggle for self-control is matched by his increased denial of responsibility. Hence Petraeus.

Bush's unyielding personality would have been best suited to the endless trench warfare of World War I, as a true compatriot of the disastrous British Gen. Douglas Haig. His mind is geared toward a static battlefield. For low-intensity warfare, such as in Iraq, "an authoritarian cast of mind would be a crippling disability," wrote British expert Norman F. Dixon in his classic work, "On the Psychology of Military Incompetence." "For such 'warfare,' tact, flexibility, imagination and 'open minds,' the very antithesis of authoritarian traits, would seem to be necessary if not sufficient."

Bush's ever-inflating self-confidence hides his gaping fear of failure. His obsession with deference demands exercises of humiliation that never satisfy him. His unwavering resolve is maintained by his adamant refusal to wade into the waters of ambiguity. "You can't talk me out of thinking freedom's a good thing!" he protests to his biographer. For Bush, even when he is long out of office, presiding at his planned library's Freedom Institute -- "I would like to build a Hoover Institute" -- victory will always be just around the corner.

Shares