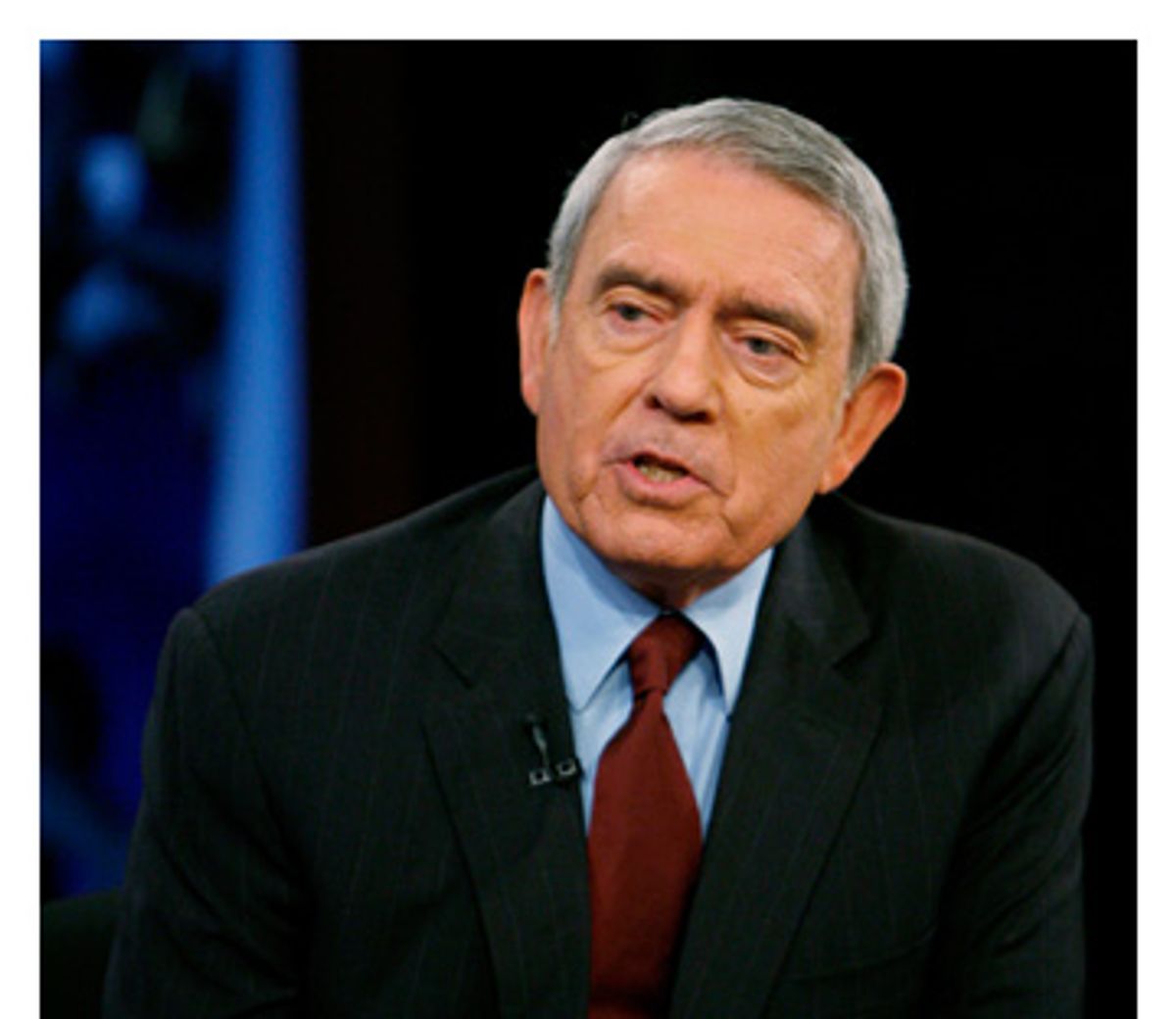

Dan Rather's complaint against CBS and Viacom, its parent company, filed in New York state court on Sept. 19 and seeking $70 million in damages for his wrongful dismissal as "CBS Evening News" anchor, has aroused hoots of derision from a host of commentators. They've said that the former anchor is "sad," "pathetic," "a loser," on an "ego" trip and engaged in a mad gesture "no sane person" would do, and that "no one in his right mind would keep insisting that those phony documents are real and that the Bush National Guard story is true."

If the court accepts his suit, however, launching the adjudication of legal issues such as breach of fiduciary duty and tortious interference with contract, it will set in motion an inexorable mechanism that will grind out answers to other questions as well. Then Rather's suit will become an extraordinary commission of inquiry into a major news organization's intimidation, complicity and corruption under the Bush administration. No congressional committee would be able to penetrate into the sanctum of any news organization to divulge its inner workings. But intent on vindicating his reputation, capable of financing an expensive legal challenge, and armed with the power of subpoena, Rather will charge his attorneys to interrogate news executives and perhaps administration officials under oath on a secret and sordid chapter of the Bush presidency.

In making his case, Rather will certainly establish beyond reasonable doubt that George W. Bush never completed his required service in the Texas Air National Guard. Moreover, Rather's suit will seek to demonstrate that the documents used in his "60 Minutes II" piece were not inauthentic and that he and his producers acted responsibly in presenting them and the information they contained -- and that that information is true. Indeed, no credible source has refuted the essential facts of the story.

Most cases of this sort are usually settled before discovery. But Rather has made plain that he is uninterested in a cash settlement. He has filed his suit precisely to be able to take depositions.

In his effort to demonstrate his mistreatment, Rather will detail how network executives curried favor with the administration, offering him up as a human sacrifice. The panel that CBS appointed and paid millions to in order to investigate Rather's journalism will be exposed as a shoddy kangaroo court.

Rather's complaint has already asserted a pattern of network submission to administration pressure, beginning with the Abu Ghraib story. In early 2004, Mary Mapes, a producer for "60 Minutes II" with more than two decades of experience, uncovered the torture at the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq. Her sources were sound and the evidence incontrovertible, but according to Rather's complaint, "CBS management attempted to bury" the story. In a highly unusual move, then CBS News president Andrew Heyward and then senior vice president Betsy West personally intervened to demand editing changes and ever more "substantiation."

Rather's suit states that "for weeks, they refused to grant permission to air the story" and "continued to 'raise the goalposts,' insisting on additional substantiation." Even after Mapes gained possession of some of the now-infamous photographs of the torture of prisoners at Abu Ghraib (a full set of which was later obtained and posted by Salon), the news executives suppressed the story, "in part," according to Rather's suit, "occasioned by acceding to pressures brought to bear by government officials."

Gen. Richard Myers, then chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, called Rather at his home, sources close to the case told me, telling him that broadcasting the story would endanger "national security." Myers explained to Rather that U.S. soldiers, just then poised for an assault on Fallujah, would be demoralized and suggested that Rather and CBS might threaten the outcome of the battle and the soldiers' safety.

Only when Seymour Hersh, investigative reporter for the New Yorker, relying on different sources from Mapes', unearthed the Abu Ghraib story and CBS executives learned that the magazine was about to scoop the network did they grudgingly permit it to be aired. "Even then," Rather's suit states, "CBS imposed the unusual restrictions that the story would be aired only once, that it would not be preceded by on-air promotion, and that it would not be referenced on the CBS Evening News." Feeling forced against their will to broadcast a story they knew was accurate, CBS's executives did everything within their power to ensure the public would pay as little attention to it as possible by prohibiting any mention of it. CBS's self-censorship set the stage for its reaction to the Bush National Guard story.

The widely accepted account that Mapes and Rather's original piece on Bush and the Guard was unproved and discredited has been based on the notion that the documents revealed were false. But three years after the heated controversy exploded, these premises appear very uncertain in the cold light of day.

Upon graduation from Yale in 1968, George W. Bush was accepted into the Texas Air National Guard, known as the "Champagne Unit" for serving as a haven for the privileged sons of the Texas elite seeking to escape duty in Vietnam. Through carefully placed calls made by Bush family friends, Bush was edged ahead of a 500-man waiting list. Then, after failing to complete his required hours of flight, he requested transfer to a unit in Montgomery, Ala. But there is no proof that he ever performed any of his service there; he refused to take a physical and was grounded. Ordered to return to his Houston base, he simply disappeared. Yet he was honorably discharged in 1973, though there is no proof that he had fulfilled his obligation.

During the 2000 campaign, the Boston Globe reported a number of discrepancies in Bush's National Guard record. However, the rest of the national press corps virtually ignored the Globe's stories, instead preferring to swarm around fictions about Al Gore helpfully stoked by the Bush campaign. Bush refused to make public his military records, in contrast to his principal primary opponent, Sen. John McCain, who had released his. But the press collectively let the matter pass. Nonetheless, the gaps in Bush's service as reported by the Globe had not been answered and hung in the air, if anyone cared to pursue them.

After breaking the Abu Ghraib story, Mapes, who lived in Texas and had reported on Bush when he was governor, began looking into the National Guard episode. By then, Sen. John Kerry, a decorated Vietnam War hero who was awarded the Silver and Bronze stars, had emerged as the Democratic candidate. The Bush operation arranged for funding a front group called Swift Boat Veterans for Truth to mount a smear campaign that Kerry had been dissembling all these years about his medals. Kerry's campaign, like Gore's, chose not to dignify obvious lies by responding, and the press lagged behind the story as it gained traction. Discrediting Kerry's greatest biographical asset was calculated to compensate for Bush's hidden liability. In February 2004, the Washington Post followed on the Boston Globe articles of 2000, and its reporters were unable to find anyone that could corroborate Bush's claim that he had served at an Alabama air base in 1972. To an aggressive journalist like Mapes it seemed logical to examine Bush's National Guard story, which remained a mystery.

The opaque story was partly illuminated by a piece in Salon, written by Mary Jacoby, on Sept. 2, 2004. Offering extensive documentation, including photographs and letters, Linda Allison, who had housed Bush during his missing year, explained that his drunken misbehavior was creating havoc for his father's political aspirations and that the elder Bush asked his old friend Jimmy Allison, a political consultant from Midland, Texas, now living in Alabama, to handle the wastrel son. "The impression I had was that Georgie was raising a lot of hell in Houston, getting in trouble and embarrassing the family, and they just really wanted to get him out of Houston and under Jimmy's wing," Linda Allison told Salon. During the time the younger Bush was under the watchful eye of the Allisons, he never went to a National Guard base or wore a uniform. "Good lord, no. I had no idea that the National Guard was involved in his life in any way," said Allison. She did, however, remember him drinking, urinating on a car, screaming at police and trashing the apartment he had rented.

On Sept. 8, "60 Minutes II" broadcast its story. It featured former Texas Lt. Gov. Ben Barnes, a Democrat, who disclosed that just before George W. Bush would be eligible for the draft, a mutual friend of then Rep. George H.W. Bush asked him to help procure the younger Bush a spot in the "Champagne Unit." Barnes appeared on camera, saying: "It's been a long time ago, but he said basically would I help young George Bush get in the Air National Guard. I was a young, ambitious politician doing what I thought was acceptable. It was important to make friends. And I recommended a lot of people for the National Guard during the Vietnam era -- as speaker of the House and as lieutenant governor. I would describe it as preferential treatment."

Then Rather, acting as correspondent, introduced new material drawn from the files of Col. Jerry Killian, Bush's squadron commander: "'60 Minutes' has obtained a number of documents we are told were taken from Col. Killian's personal file. Among them, a never-before-seen memorandum from May 1972, where Killian writes that Lt. Bush called him to talk about 'how he can get out of coming to drill from now through November.' Lt. Bush tells his commander 'he is working on a campaign in Alabama ... and may not have time to take his physical.' Killian adds that he thinks Lt. Bush has gone over his head, and is 'talking to someone upstairs.'"

Another Killian memo contained the coup de grâce: "I ordered that 1st Lt. Bush be suspended not just for failing to take a physical ... but for failing to perform to U.S. Air Force/Texas Air National Guard standards. The officer [then Lt. Bush] has made no attempt to meet his training certification or flight physical."

Within minutes of the conclusion of the broadcast, conservative bloggers launched a counterattack. The chief of these critics was a Republican Party activist in Georgia. Almost certainly, these bloggers, who had been part of meetings or conference calls organized by Karl Rove's political operation, coordinated their actions with Rove's office.

Questioned for the "60 Minutes" story, White House communications director Dan Bartlett had not denied the story but simply characterized it as "dirty." The right-wing bloggers raised questions about the authenticity of the Killian documents, arguing that typewriters of the time lacked the specific superscript in the documents, that the proportional spacing was wrong and the font anachronistic, and that therefore they were likely fabricated on a computer. Various handwriting and typewriter experts weighed in, some challenging the documents' authenticity. The press almost uniformly took the absence of a universal opinion of experts as proof of the documents' falsity. Because they could not be proved with complete certainty to be authentic, they must be counterfeit.

While the battle over the authenticity experts and assorted inconclusive sources continued, CBS interviewed Marian Carr Knox, who had been Col. Killian's assistant when the memos were allegedly produced. She didn't recall typing them and didn't believe Killian had written them (though various handwriting experts had verified his signature), but she also asserted, "The information in here is correct."

Under fire, CBS executives reeled backward. On Sept. 20, Heyward issued an apology: "Based on what we now know, CBS News cannot prove that the documents are authentic, which is the only acceptable journalistic standard to justify using them in the report. We should not have used them. That was a mistake, which we deeply regret." And Rather chimed in: "If I knew then what I know now -- I would not have gone ahead with the story as it was aired, and I certainly would not have used the documents in question." With these self-abasing mea culpas (Rather claims in his complaint that his statement was "coerced"), the veracity of the story about Bush's past seemed to be settled in his favor. But the underlying facts of the story were not discredited; nor was the authenticity of the documents resolved.

The day after these apologies CBS announced the creation of a review panel to determine "what errors occurred." Two Bush family loyalists, Richard Thornburgh, former attorney general in the elder Bush's administration, and Louis Boccardi, former executive editor and CEO of the Associated Press, were chosen to head the internal investigation. Thornburgh had been the subject of critical Rather reports, while Boccardi felt close and indebted to the elder Bush for being helpful as vice president in gaining the release of AP reporter Terry Anderson, held hostage for six years in Lebanon. Lawyers in Thornburgh's firm with no background in journalism and media performed the real work of the panel and wrote its final report.

As the panel called witnesses, Sumner Redstone, CEO of Viacom (CBS's owner), declared his interest in the 2004 election. "I look at the election from what's good for Viacom. I vote for what's good for Viacom. I vote, today, Viacom," he said. In fact, Viacom had a number of crucial issues before the Federal Communications Commission, including loosening media ownership rules. "I don't want to denigrate Kerry," said Redstone, "but from a Viacom standpoint, the election of a Republican administration is a better deal. Because the Republican administration has stood for many things we believe in, deregulation and so on. The Democrats are not bad people ... But from a Viacom standpoint, we believe the election of a Republican administration is better for our company."

Rather believed that the panel would conduct a fair-minded inquiry. But he learned that neither he nor Mapes would be allowed to cross-examine witnesses. They heard from some researchers on the "60 Minutes II" staff that before they had been questioned, a CBS executive had told them that they should feel free to pin all blame on Rather and Mapes. CBS had told Rather to cease investigating the story and had even hired a private investigator of its own, Erik Rigler. Rather and Mapes discovered that Rigler's investigation had uncovered corroboration for their story. Rather's complaint states that "after following all the leads given to him by Ms. Mapes, he [Rigler] was of the opinion that the Killian Documents were most likely authentic, and that the underlying story was certainly accurate." But rather than probing Rigler on his findings, the panel, to the extent its lawyers questioned him in a single telephone call, "appeared more interested whether Mr. Rigler had uncovered derogatory information concerning Mr. Rather or Ms. Mapes, as to which he had no information," according to the Rather complaint. Rigler's report was suppressed, never presented to the panel, and remains suppressed by CBS. Nor did the panel fully question James Pierce, the handwriting expert consulted by "60 Minutes" who insisted that the signature on the documents was surely Killian's.

When Mapes appeared before the panel, she was harshly questioned at length about her use of the word "horseshit." On the issue of the special privileges granted to those sons of wealth in the "Champagne Unit," Thornburgh asked her, "Mary, don't you think it's possible that all these fine young men got in on their own merits?"

When it came to the merits of the facts the panel elided them. It never addressed the facts at all. Instead it criticized the "60 Minutes" team for failing to "obtain clear authentication" of the Killian documents, among other "errors," though it admitted it could not prove one way or another whether they were inauthentic. Mapes and three other producers were dismissed. "60 Minutes II" was abolished. And on the day after Bush's reelection, Rather was unceremoniously fired. His contract had called for him to continue as anchor for an additional year and then to serve as a correspondent for "60 Minutes" and "60 Minutes II," but that promise was not honored. CBS believed that by severing its link with Rather it could put the whole incident behind it and begin a new happy relationship with the ascendant Republicans.

An article by James Goodale, former vice chairman and general counsel of the New York Times, in the New York Review of Books on April 7, 2005, and his subsequent exchange with Thornburgh and Boccardi, went little noticed. Goodale found the panel's report filled with flaws, lacking a factual basis, revealing an absence of due diligence and due process, and substituting empty legal concepts and language for any understanding of the actual gritty practice of journalism. Goodale determined that the "underlying facts of Rather's '60 Minutes' report are substantially true." He observed, "Since the broadcast, no one has come forward to say the program was untruthful."

Goodale's summation rejected the report and left its credibility in tatters: "The rest of the report, which is directed to the newsgathering process of CBS, is flawed. The panel was unable to decide whether the documents were authentic or not. It didn't hire its own experts. It didn't interview the principal expert for CBS. It all but ignored an important argument for authenticating the documents -- 'meshing.' It did not allow cross-examination. It introduced a standard for document authentication very difficult for news organizations to meet -- 'chain of custody' -- and, lastly, it characterized parts of the broadcast as false, misleading, or both, in a way that is close to nonsensical. One is tempted to say that the report has as many flaws as the flaws it believes it has found in Dan Rather's CBS broadcast."

But Goodale's magisterial and experienced voice seemed to be a faint cry in the wilderness. Who, after all, cared anymore?

In November 2005, Mapes published a memoir, "Truth and Duty," containing her memo to Thornburgh and Boccardi that they had failed to include in the appendix of the panel's report, although they reproduced many other memos and documents. Mapes' argument was that the Killian documents "meshed" with the facts in precise and nuanced ways. "The Killian memos, when married to the official documents, fit like a glove," she wrote. "There is not a date, or a name, or an action out of place. Nor does the content of the Killian memos differ in any way from the information that has come out after our story ... In order to conclude that the documents are forged or utterly unreliable, two questions must be answered: 1) how could anyone have forged such pristinely accurate information; and 2) why would anyone have taken such great pains to forge the truth?" But Mapes' book, like Goodale's article, was all but ignored.

Rather has always been an uncomfortable figure, sometimes abrasive, sometimes strangely inappropriate or baffling, given to rustic rhetoric at odd moments, and sometimes and suddenly lapsing into teary sentimentality or bursts of patriotic doggerel. Since his confrontations as the correspondent covering the Nixon White House, conservatives have targeted him as a symbol of the despised "liberal media." However idiosyncratic, Rather stood for the remnants of CBS's tradition of speaking truth to power, as Edward R. Murrow did finally about Sen. Joseph McCarthy and Walter Cronkite did finally about the Vietnam War and Watergate. The corporate unease with Murrow's outspokenness, leading to the cancellation of his weekly program, "See It Now" (depicted in the recent film "Good Night, and Good Luck"), was little different from the unease with Rather a half-century later. At last, the corporation's necessity for demonizing Rather coincided with the long-standing conservative demonizing.

When CBS replaced the edgy Rather with the sugary Katie Couric as anchor of the "Evening News," it imagined it had solved its problem, its "errors." The news would get softer, the Republicans in control of the White House and Congress would be nicer, Viacom would grab more media, and ratings would climb. Thus, dismissing Rather would yield untold dividends. Unfortunately for CBS's visionaries, none of that has worked out as planned. Couric simply lacks basic journalistic instincts and skills, and the "CBS Evening News" is at rock bottom in ratings and sinking farther.

Rather could have simply allowed the statute of limitations to run out, lived off his millions, and faded away. But the incident ate at him. On one level, the Bush National Guard story is about Bush and the National Guard. On another, of course, it is about Rather's reputation. But on yet another it is about CBS's overwhelming desire to please the Bush White House and censor itself. The White House campaign against Rather has been so successful that many in the national press corps behave as though in mouthing its talking points they are demonstrating their own independent thought.

On Sept. 20, the day after he filed his suit, Rather said, "The story was true." Rather's suit may turn into one of the most sustained and informative acts of investigative journalism in his long career. He is not going gentle into that good night.

Shares