Under crisis conditions of an extraordinary magnitude political leadership of the highest level will be required in the next presidency. The damage is broad, deep and spreading, apparent not only in international disorder and violence, the unprecedented decline of U.S. prestige, and the flouting of our security and economic interests but also in the hollowing out of the federal government's departments and agencies, and their growing incapacity to fulfill their functions, from FEMA to the Department of Justice.

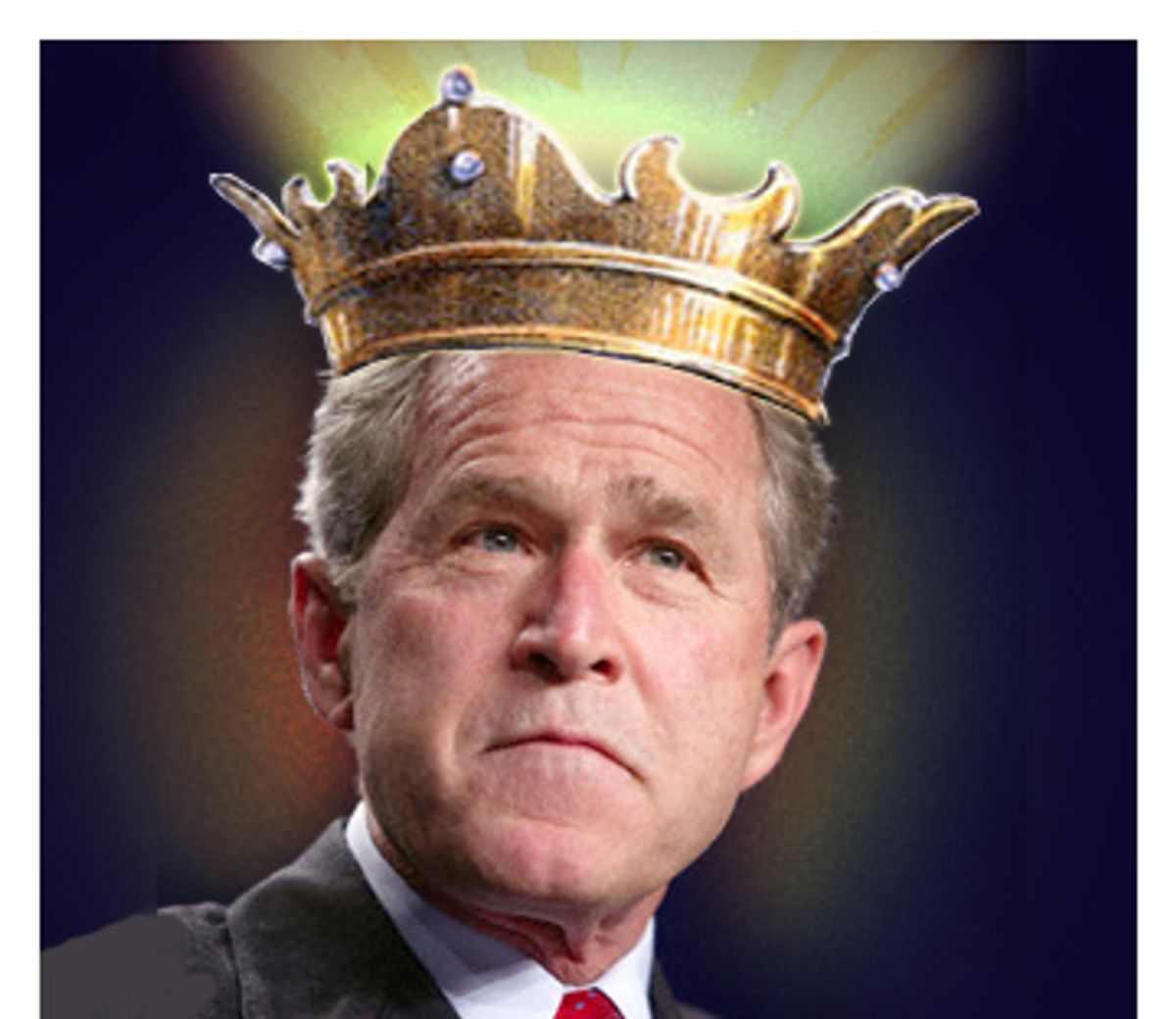

The more rigid the current president is in responding to the chaos he has fostered, the more the Republicans still supporting him rally around him as a pillar of strength. His flat learning curve, refusal to admit error and redoubling of mistakes are regarded as tests of his strong character. Whatever his low poll ratings of the moment, his stubborn adherence to failure is admired as evidence of his potency.

The patently perverse notion that weakness is strength is the basis of Bush's remaining credibility within his party. His abuse of presidential power is seen as his great asset rather than understood as his enduring weakness. But when the president assumes all the responsibility, he also receives all the blame, which becomes unitary and unilateral. Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson stated the constitutional principle in the 1952 Youngstown Steel case: "When the President takes measures incompatible with the expressed or implied will of Congress, his power is at its lowest ebb. Presidential claim to a power at once so conclusive and preclusive must be scrutinized with caution, for what is at stake is the equilibrium established by our constitutional system."

In his waning year, Bush is pointedly indifferent to the predictable consequences of his collapse. According to those who have met with him recently, he envisions himself as a noble idealist having made moral decisions that will vindicate him generations from now.

Despite the obvious shortcomings of his policies, he has startlingly succeeded in reshaping the executive into an unaccountable imperial presidency. And Bush's presidency is now accepted as the only acceptable version for major Republican candidates who aspire to succeed him. All of them have pledged to extend its arbitrary powers. Their embrace of the imperial presidency makes the 2008 election a turning point in constitutional government.

This campaign pits two parties running on diametrically opposite ideas of the presidency and the Constitution. There has not been such a sharp divergence on the foundation of the federal system since perhaps the election of 1860.

Two models of the presidency are at odds, one whose founding father was George Washington, the other whose founding father was Richard Nixon. Under the aegis of Dick Cheney, who considered the scandal in Watergate to be a political trick to topple Nixon, the original vision has been entrenched and extended. Cheney is the pluperfect staff man, beginning as Donald Rumsfeld's assistant in the Nixon White House, and was aptly code-named "Backseat" by the Secret Service when he pulled the strings in the Ford White House as chief of staff. For Cheney and the president under his tutelage, eagerly acting as "The Decider" on decision memos carefully packaged by "Backseat," the Constitution is a defective instrument remedied by unlimited executive power.

Like Nixon, Bush and Cheney act on the idea that the more they operate outside the constitutional system, the stronger they are. But, unlike Nixon, they are willfully contemptuous of facts and evidence, believing that unfettered power gives them the authority to create or impose their own. Bush and Cheney have refined and simplified Nixon's concept, purging it of his realism and flexibility. There will be no opening to Iran as there was an opening to China. In Bush's imperial presidency, neoconservatism meets Nixonianism, the ideology providing the high concept of low politics.

In ways that Nixon did not achieve, Bush has reduced the entire presidency and its functions to the commander in chief in wartime. And in order to sustain this role he has projected a never-ending war against a distant, faceless foe, ubiquitous and lethal. Fear and panic became the chief motifs substituting for democratic persuasion to engineer the consent of the governed, as Jack Goldsmith, Bush's former director of the Office of Legal Counsel in the Justice Department, explains in "The Terror Presidency." He writes, "Why did the administration so often assert presidential power in ways that seemed unnecessary and politically self-defeating? The answer, I believe, is that the administration's conception of presidential power had a kind of theological significance that often trumped political consequences."

The imperial president must by definition be an infallible leader. Only he can determine what is a mistake because he is infallible. Stephen Bradbury, the acting director of OLC in the Justice Department who wrote secret memos justifying the torture policy in 2005, defined this Bush doctrine in congressional testimony in 2006: "The president is always right." Placing his statement in context, Bradbury explained that he was referring to "the war paradigm," the neoconservative idea of the Bush presidency, "the law of war," wherein the president is a law unto himself. This notion seems medieval, but it is central to the new radical Republican notion of the presidency. When Bradbury uttered his extraordinary remark, he did not think he was saying anything unusual. His statement, after all, was only a corollary of Nixon's infamous one made in his post-resignation interview with David Frost, "When the president does it, that means it's not illegal." Bush exceeds Nixon in his claim of divine inspiration from the Higher Father.

Every executive policy does not exist on its own merit but as part of an overarching plan to establish an executive who rules by fiat. Enforcing these policies is intended to break down resistance to aggrandizing unaccountable power for the presidency. Warrantless domestic surveillance is a case in point.

Torture is the linchpin of the new Republican argument on presidential power. Abuse of detainees is the metaphor for beguiling the public into supporting abuse of the presidency. The sadomasochistic ecstasy of torture and the thrill of vengeance are the ultimate appeal of the party of torture. Projecting violence against accused terrorists in an endless war is a deep political strategy to forge and fortify a new regime. This novel form of government, never before installed in the U.S., despite precursors from Nixon's planned seizure of powers, is being cemented into place so that its penetrability and removal will become extraordinarily difficult. Those who undertake the task of rebuilding the structure will be vulnerable to harsh political attacks as unpatriotic and subversive. Thus restoring American constitutional government after Bush demands the most strategic political and bureaucratic genius.

So vital is torture to the imperial presidency that Bush staked the nomination of his new attorney general, Michael Mukasey, on his refusal to oppose a ritual designed during the Spanish Inquisition to purge sinful heresy: waterboarding. Were Mukasey to have called waterboarding torture, as it surely is, he would have been obligated to prosecute those responsible for war crimes.

Mukasey's testimony was symptomatic of the new constitutional order forged by Bush. Even more insidious, the secretive process to which the administration subjected Mukasey to get him to toe the line underlines that the radical changes Bush has made in the presidency are not merely for one administration, but intended for all that follow.

On Oct. 25, Sen. Dick Durbin of Illinois received written responses from Mukasey to questions he had submitted. In one question, Durbin asked about a report that Mukasey had met with unnamed conservative figures to discuss his legal views and allay any misgivings they might have.

The list of names extracted from Mukasey by Durbin passed by unnoticed in the controversy. Mukasey revealed that on order of "officials within the White House" he sat down with six prominent right-wing leaders, whose gathering constituted a de facto subcommittee of the "Inner Party" of the conservative movement. Those present were Reagan's attorney general, Edwin Meese III; former Reagan and Bush I legal officials Lee Casey and David Rivkin; the executive vice president of the Federalist Society, Leonard Leo; the president of the Ethics and Public Policy Center, Edward Whelan; and the chief counsel for the American Center for Law and Justice (founded by Pat Robertson), Jay Sekulow.

Mukasey's meeting with this group at the insistence of the White House amounted to a supra-official confirmation hearing. The incident demonstrates that the Bush imperial presidency is a central tenet of the permanent elite of the party extending beyond his administration. Politicizing paranoia, subsuming intelligence by ideology, purging and deputizing prosecutors, dismissing law by fiat (signing statements) and holding in contempt checks and balances are not temporary measures. It is no accident, as the Marxists (or neoconservatives) say, that President Bush will address the 25th anniversary gala of the Federalist Society on Thursday.

All major Republican candidates for president have embraced Bush's imperial presidency, but none has surpassed in his fervor Rudy Giuliani. The possibility of holding unaccountable power and conducting a presidency on the footing of what one of his closest advisors, the literary critic as foreign policy expert manqué Norman Podhoretz, has called "World War IV" has wildly excited him. Giuliani time, indeed.

Whether Giuliani becomes the nominee or not, he has defined more clearly than the others the coming themes of the Republican campaign for 2008. His political premise in running for mayor of New York was that the city was under siege, overrun by crime and chaos. His answer to crime was his new police commissioner: Bernard Kerik, the lawless lawman.

Giuliani's image of New York then is transformed now into an image of the country besieged from within and without. As mayor he stoked inflammatory racial confrontation and basked in demagogy. His heated and cynical paranoid style has gone international. (For cynicism, few episodes exceed his showdown in 2000 with the Brooklyn Museum over an African artist's painting of a portrait of Jesus using elephant dung as a material when Giuliani was slipping in the polls against his prospective opponent for the U.S. Senate, Hillary Clinton. When the chips are down, Giuliani always looks for the elephant chip.) Whether he becomes the Republican candidate or not, he has helped consolidate Bush's authoritarian model as the only acceptable one for Republicans.

Now, on a personal note, I have reached the end of my critique of the Bush administration, having elaborated it for years. (In fact, my book on "The Strange Death of Republican America" will be published in April 2008.) As events continue to unfold there will undoubtedly be many more things to say about Bush, Cheney, their administration and the Republican field. But given the momentous stakes, I have decided that nothing is more important than committing myself wholly to the outcome. Therefore, beginning here, the tone changes.

Readers know of my background in the Clinton White House. (See "The Clinton Wars.") They are familiar with my long friendship with Sen. Hillary Clinton. When she recently asked me to join her campaign as senior advisor I felt I must accept, though not out of obligation but, rather, wholeheartedly. There will be other times and places for me to explain how I have seen her grow into the person I now feel is best qualified and suited to restore the presidency, an office I observed and participated in for four years and about whose nature, I know from working closely with her, she has a deep grasp.

I believe that the reason the Republicans have promoted the talking point that Hillary is unelectable is that they fear that more than any other candidate she can create a majority coalition, win and govern. They fear more than loss in one election; they fear the end of the Republican era beginning with Nixon. They know that she has the knowledge, skill and ability to govern. They know that she has already taken everything they can throw against her and is still standing.

Just as the disintegration of the Democrats brought about the rise of the Republicans, the collapse of the Republicans has created an opening for the Democrats. But the Democrats have been victims of their own false euphoria, sanctimony and illusions before. Now, only the Democrats can revive the Republicans. Nixon, Reagan and Bush were all beneficiaries of Democratic disarray and strategic incompetence. The Democrats have snatched defeat from the jaws of victory before and it can happen again, even under these circumstances, when history is turning the Democrats' way.

The Democrats at key junctures have been seduced by the illusion of anti-politics to their own detriment. Anti-politics upholds a self-righteous ideal of purity that somehow political conflict can be transcended on angels' wings. The consequences on the right of an assumption of moral superiority and hubris are apparent. Their plight stands as a cautionary tale, but not only as an object lesson for them. Still, the Republican will to power remains ferocious. The hard struggle will require the most capable political leadership, willing to undertake the most difficult tasks, and grace under pressure.

Shares