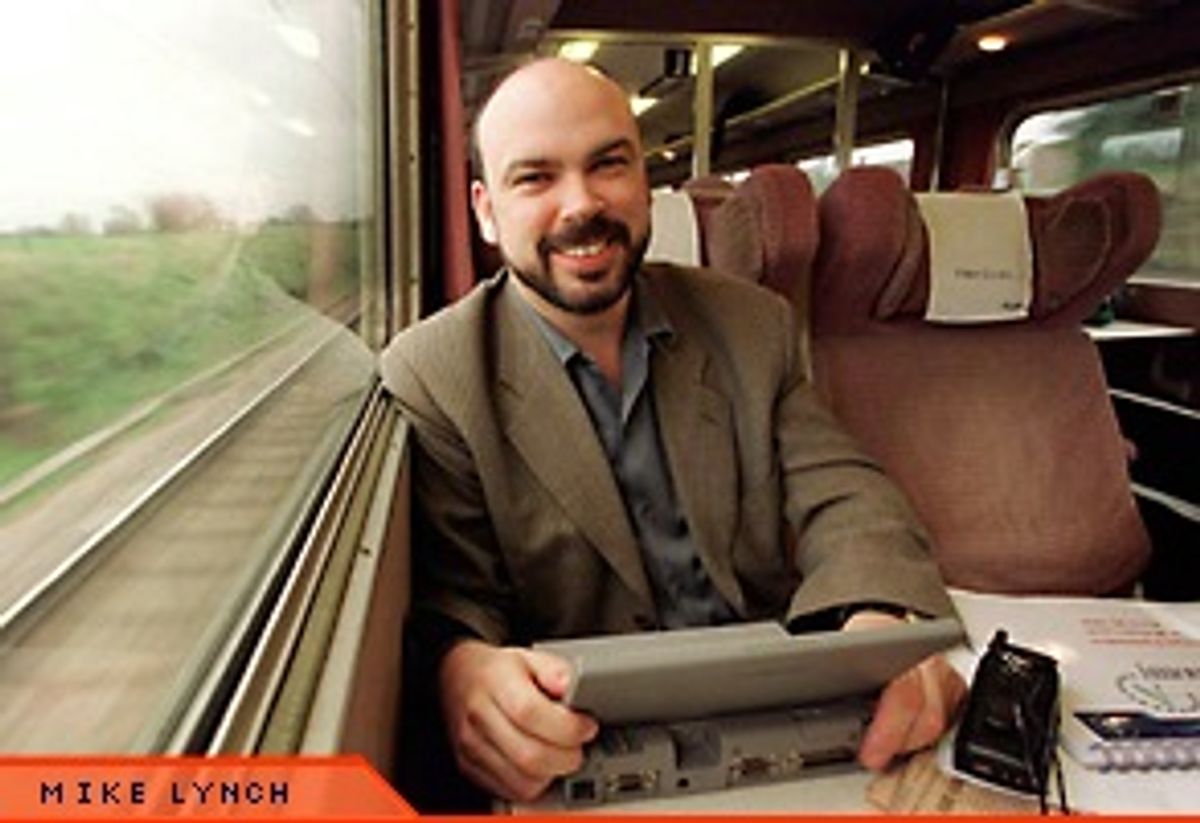

Mike Lynch is Britain's first software billionaire. After years of hype about "Silicon Fen," the high-tech concentration growing up in and around Cambridge, England, it finally happened: We got a multibillion-dollar company.

Lynch is founder and CEO of Autonomy, a maker of software that ties together all kinds of unstructured information -- what's now known as knowledge management. The term wasn't in heavy use back in 1991, when Lynch borrowed 2,000 pounds (about $3,000) from an English pop promoter in a pub to start his first company, Cambridge Neurodynamics, from which Autonomy spun off in 1996. Lynch still sits on Neurodynamics' board, but he believes there is more scope in Autonomy, whose software and techniques he expects to be everywhere in a couple of years.

In a corporate context, you might use Autonomy's software to display links to material in the corporate archives that's relevant to a memo you're writing. On the Web, it might display links to news stories related to the ones you're reading.

Both companies are built upon the statistical principles derived by Thomas Bayes, an 18th century Presbyterian minister and mathematician whose formulations underlie the pattern-recognition algorithms that help computers behave more like humans, enabling them to recognize context and understand connections. Bayes' ideas on statistical models might never have been heard of had he not left his papers and 100 pounds to his friend and fellow clergyman Richard Price. Price published his late friend's "An Essay Towards Solving a Problem in the Doctrine of Chance," and promoted it by saying it proved the existence of God. In a computer context, however, Bayes' theorem pulls many probabilities together, enabling the computer to pick an answer out of multiple, often conflicting, pieces of information.

I have to ask because every mathematician I knew when I was briefly a math major worshipped him -- were you a fan of Martin Gardner's mathematical games column in Scientific American?

To be honest, no. But I came from an engineering background to math, and so it was very much driven by "What do I need to solve the problem?" rather than by delight in pure mathematics. But then, I would say that the area that I work in is pure philosophy anyway, because my area of research -- though I don't get to do pure research anymore, only what I think of as applied research -- is perception. Perception is very interesting because if you understand Bayes, if you start to think about it, you can see why Bayes is taught in philosophy classes these days.

I thought you were going to say he was taught in business schools.

Well, he ought to be, yes -- but keep that a secret.

So: perception.

If you understand that the world exists only as you perceive it, that is actually only a cup in any sense because you perceive it as a cup. Otherwise, it's a set of light rays coming off an object, or it's a set of electrical impulses between synapses in the brain, or it's a set of spinning electrons. We've been very obsessed with what people call materialism.

Physics was the great subject of the 20th century -- how the world is, out there. But many of the more interesting questions aren't about how the world is out there, or whether it is out there even, but how people perceive it, so you get the whole problem of pattern recognition or perception. Mental illness becomes fascinating from this viewpoint.

That's where you come down to consensus reality.

Yes, but the whole point about perception is that it's an artificial construction, because to the person who's part of an alternative reality, it's their reality; the fact that you're telling them you see something different is irrelevant. The other thing is -- take one of those computer screens. We could create random patterns on there, and of those a tiny, tiny subset would be perceived by us as representing something in the real world. So if you start looking at perception from a mathematical point of view, you have this massive dimensionality of possibilities, and the world we exist in is only a very small part of it.

Did you read much science fiction as a kid?

Relatively little, actually -- more literature. One of the wonderful things about the English school system is I ended up doing ancient Greek and things like that. You could have this same conversation in terms of the Greek philosophers as in terms of computer science and mathematics. They were rather forward looking. But coming back to the point, perception is a lot more powerful subject than people think, because you can argue that in terms of our view of the universe -- or my view of the universe -- perception can be more powerful than physics can be.

Does this mean you should start experimenting with different kinds of drugs?

That's a very interesting question -- which I'm not going to answer as the CEO of a public company! But you read fascinating accounts from people who [experimented with drugs] from a scientific point of view in the 1960s. They're especially interesting, as are dreams, if you know about the mathematics of pattern recognition. Another thing I find very interesting is near-death experiences, from a point of view of pattern recognition.

You're frequently quoted as saying you want Autonomy to become "the Oracle of unstructured data."

The problem we address is completely generic. People often just don't understand the ramifications of that. I don't think you're going to be able to sell software in two years' time that can't make sense of information, because the amount of unstructured information in business is doubling every three months at the moment.

Of course, Larry Ellison has Bill Gates to compete with, at least in his own mind. But you're in a class by yourself, aren't you? There isn't anybody else in Britain.

There's a different motivation for me, though I get very annoyed about people that make untrue comments about their technology vs. ours. That's the kind of thing that gets me, rather than some sort of scoreboard.

And you're not moving to a tax haven.

I like it too much here. In the country here, they don't have very many gadgets at all. They have clocks that go "tick."

It's a perspective thing. In the village where I live there's a tower that was built about 900, probably to look for the Vikings coming by sea. In the church there are big slabs commemorating people, and the church stonemason was a bit of a character, so he wrote these epigraphs with implications, like "having risked the marriage bed a second time," or "never one to be silent in his views," and you read them and think, "Yes, people lived here." And both their lives were different and their lives were the same.

I went to see Molihre for the first time a year ago, and I was stunned; the intrigue, backbiting and politics could have been straight out of today.

Like Bayes, Austen, Shakespeare ... these greats who are all having an impact now. I always think it's sad that people don't get to find out what impact they had on the world. You sort of wish you could wake Bayes up for five minutes and say, "You won't believe this, but ..."

He's actually buried not far from William Blake. They could have a pretty interesting discussion if they woke up for five minutes.

But it sort of underlines an insidious arrogance about our age, that we know more and are more intelligent than our predecessors. If you talk to my 25-year-olds down there, they've grown up with this endemic idea that we are somehow brighter than our forefathers were. I actually got knocked out of that by a very strange example, a model steam engine, of all things.

When people were apprentices they used to have to build a masterwork replica of a full-size steam locomotive. To make one of these things you have to find out how a steam engine works. And the problem is, there is high pressure in the boiler, and you're heating water and turning it into steam, and very quickly you run out of water. So you have to get the water back in against the highest pressure in the system. There's a thing called a steam injector, which is a system where you blow steam into a specially shaped cavity, and it creates a thermodynamic shock wave, which instantaneously creates a pressure rise, which will push some water into the boiler. And then you think, this was invented in the 1860s?

What's your favorite gadget?

My new Philips MP3 player. I'm getting into the whole Napster thing at the moment. And I really love my little Toshiba Libretto.

Why is it that math and music so often go together? You play saxophone.

Contrary to the nerd image, good mathematicians are often good musicians, whereas literature students know nothing about science. Math at a pure research level is like playing jazz.

When I first saw Autonomy's software in 1996, it was designed to run on individual PCs; it had these cartoon dogs I hated that ran endlessly while it searched for sites relevant to your query. It was unbelievably slow and, after hours of waiting, didn't come up with sites I didn't know about.

People either loved or hated the dogs. Those were the early days, when we were taking a client approach. Moving it to the server was when the business took off -- the market caught up with us and people started setting up these big news sites. In 1996, it wasn't clear that the client wouldn't be where these things would be done. Then the market settled down, and now it's moving the other way because people are beginning to question why they have to know what a directory or a file is. It should be the computer's job to remember where I put something, not mine. Less than 5 percent of our business is search. Most of what we do is categorizing and linking. That's much more interesting, because the more information you give it the more accurate it becomes.

A fair bit of your work is done for the police. In the context of the current debates about the British Regulation of Investigatory Powers bill, do you worry about the privacy consequences of the kind of profiling and traffic analysis your products enable?

It's a debate that's sadly a bit sound-bite based at the moment. One of the things we started with at Cambridge Neurodynamics is technology that searches fingerprints. That system has put a series of rapists and serial murderers away, and I don't lose any sleep at all about that. Technology-based evidence actually makes it very hard to convict someone falsely. As long as a test is done correctly, it's incredibly powerful.

I'm actually very sympathetic to the other point of view, but the issue is not the technology but the kind of society you want to live in. Having a basically honest government is the issue, not the technology.

Shares