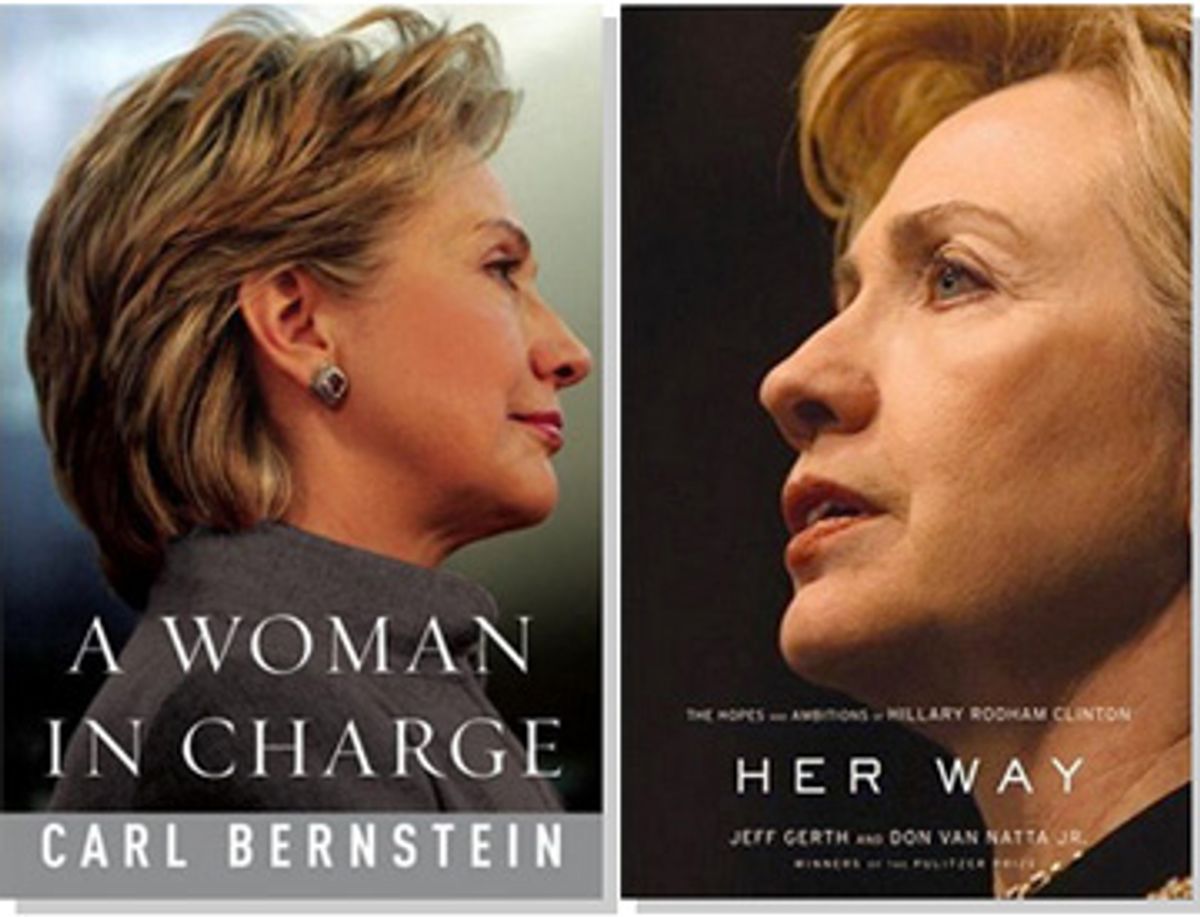

To read the latest biographies of Hillary Rodham Clinton is to marvel at how the leading aspirant to her party's presidential nomination could ever have gotten this far. She doesn't even know who she is, according to "Her Way," by Jeff Gerth and Don Van Natta Jr., and "A Woman in Charge," by Carl Bernstein, and neither do we.

Thankfully these authors assure us that they have discovered her true identity, which explains why we need still another book or two to supplement the heavily redundant library of screeds and memoirs about the Clintons, their marriage and their political quest. This most famous of women is an "enigma," whose true identity can only be discerned from the clues they provide.

Yet the opposite assertion seems equally plausible -- that having collectively gorged ourselves on profiles, gossip, testimony and text for more than 15 years, we know Hillary Clinton more intimately than we know anyone else who has ever run for president. We know far more about her difficult marriage, for instance, than we do about the vexed domestic histories of Rudolph Giuliani, Newt Gingrich or John McCain. We know far more about her professional career as an attorney and her financial assets than we do about the Washington lobbying of Fred Thompson or the hard-edged business practices of Mitt Romney.

The problem is not that we lack information about the former first lady, but that so much of what we have been told about her has been false and misleading.

Neither Gerth and Van Natta nor Bernstein quite reproduces the nasty, demeaning portrait that became so familiar in right-wing propaganda and mainstream journalism during her husband's presidency. Striving for an impression of fairness, these authors nod to Clinton's strengths, including her prodigious capacity for work, her studious approach to public service, her surprising enthusiasm for reaching across the partisan aisle, and her determination to protect her family.

All too frequently, they hark back to the clichés, however. Page after page presents us with the scheming woman whose arrogance and ambition were exceeded only by her incompetence, and who barely evaded indictment because of her impulse to conceal the truth. Only her almost superhuman will to achieve power has allowed her and Bill to overcome the consequences of their character flaws and their troubled partnership -- or so we are urged to believe.

As with all books about Hillary, each of these boasts of the hundreds of interviews and thousands of documents that undergird their conclusions. Indeed, Bernstein's jacket copy goes so far as to claim that he "reexamined everything pertinent written about and by Hillary Clinton," which sounds like a literally impossible task. Both books feature the usual surfeit of mind-reading moments (such as "Hillary began contemplating" and "Hillary knew ... in her heart"), plus the usual anonymous quotes (from "a senior aide" or "a top presidential aide" or, somewhat less plausibly, "a Hillary friend" or "a Hillary confidant") putting her in her place.

This version of Hillary Clinton, broadcast relentlessly by the Republican right and eagerly amplified by the mainstream media, would probably sound at least vaguely familiar to every literate adult on the planet. Repeated in book after book, article after article, on radio and on television, it represents one of the most sustained campaigns to denigrate a political figure in the nation's history. But that is a familiar story by now as well.

What is remarkable, at this late date, is not how many Americans feel hostility toward Hillary, but that so many still admire her -- and that after all the shrill calumniation, she remains a highly credible candidate for president. Perhaps some people have noticed that the angriest critics often seemed to be projecting their own glaring shortcomings onto their quarry. Certainly that was true of Alfonse D'Amato, Newt Gingrich, Tom DeLay and Henry Hyde, who pursued both Clintons with so much zeal and so little introspection.

Yet by now everyone, and especially the Clintons, must be accustomed to such ironies in our political theater. It is no surprise then to find Bernstein muckraking the intimate problems of the Clinton marriage, despite the spectacularly embarrassing depiction of his own domestic troubles in a landmark novel by his former wife, Nora Ephron. Nor is it a surprise to read Gerth and Van Natta arraigning Hillary Clinton for her alleged deceptions and inaccuracies, even though their own journalism has required sharp correction by New York Times editors and a federal judge, respectively.

Neither book is committed completely to the negative caricature, but there is enough of that kind of material -- and enough poorly founded speculation -- to excite the likes of Dick Morris and Matt Drudge. None of the authors can quite resist the pull of the old fables, although they make gestures toward a more complete and humanized narrative.

It is a sign of changing times that these writers, permanent fixtures of the Beltway journalistic establishment, today feel obliged to acknowledge that the Clintons really did have enemies who were seeking to destroy them. Bernstein is considerably more forthright on that score, while Gerth and Van Natta continue to defend Kenneth Starr, whose independent counsel's office provided copious leaks to them during the Monica Lewinsky investigation. (Indeed, that tacit admission is among the most interesting new facts in their book.)

Unlike Gerth and Van Natta, who frequently assume that Hillary's motivations are self-serving or opportunistic, Bernstein seems to believe that both Clintons are decent people who mainly mean to do good. He credits Hillary not only with a sincere commitment to improving the world but a deep religious faith. (He confirmed the latter with her longtime prayer partners on Capitol Hill, most of whom are Republicans.) He seems to have had considerable access to people who know her well and paid careful attention to their views. His analysis of the failure of the Clinton healthcare initiative is accurate. He has an unfortunate tendency to parrot conventional wisdom on many aspects of the Clinton White House "scandals," but he conveys the essential emptiness of Whitewater and the political double standard that it symbolizes.

As often as Bernstein extends sympathy to Clinton or her husband, however, he withdraws it on the next page. He criticizes Hillary sharply for her willingness to fight for her and her husband's political lives, then admits that she had no other choice, then lambastes her for her excesses in battle. Ultimately, he concurs with Gerth and Van Natta in affixing the burden of blame to the Clintons rather than their enemies or the press that sided so blatantly with those foes. She might reply, in a truly candid moment, that the proof is in the results. Bill Clinton survived impeachment and she went on to win her Senate seat in a landslide the following year.

Gerth and Van Natta's "Her Way" begins and concludes with a literary conceit that tells us more about the authors than about their subject, quoting a 1934 radio interview with Eleanor Roosevelt on the future prospect of a female president, who must be a person of "integrity and ability." There is irony here too, as well as a measure of how far the authors have waded beyond their historical depth. Recalling the Roosevelts is apt enough, although not in the way that Gerth and Van Natta seem to think. Like Bill and Hillary, Franklin and Eleanor confronted adversaries in the Republican right and the Hearst-dominated press who were just as bitterly determined to ruin them.

Did Gerth and Van Natta not try to imagine, when they unearthed that radio transcript, what would have happened to FDR's presidency if he and his wife had suffered the sort of scrutiny applied to the Clintons? No doubt America would have read daily gossip about the "enigma" of the Roosevelt marriage, the close relationship between the first lady and her female companion, the very close relationship between the president and a female aide, the "cover-up" of the president's crippling illness, and so on.

Between the allusions to Eleanor, they don't break much new ground. Like Bernstein, they obsess at length over the lost-and-found billing records of the Rose Law Firm, without solving the supposed mystery of their reappearance early in 1996 -- which they say aroused the suspicions of their friend Starr and his staff. They seem to assume that Hillary hid them out of embarrassment over inflated billing hours and concede that the records showed no proof of criminal activity. For some reason, it never occurred to Starr, or most of the journalists covering him, to wonder why Hillary Clinton didn't simply destroy those records if she were so inclined. Or why, even more mysteriously, she would have chosen to produce them at such an inconvenient moment for her husband's reelection campaign. Evidently they couldn't accept the simple and obvious answer: She was telling the truth.

If "Her Way" has any virtue, it can be found in the authors' effort to assess Clinton's Senate career, which Bernstein scarcely discusses at all. Assuming that Gerth and Van Natta did their best to uncover the worst, she must be quite clean. Their most troubling discovery is that her office failed to file the proper paperwork concerning a dozen "fellows" from places such as Cornell University who served on her staff. To them this is fresh proof of her penchant for secrecy and her disregard for ethical rules; to most sane people it will seem even more trivial than Gerth's original Whitewater exposé.

Decidedly not trivial, however, is their coverage of Hillary's October 2002 vote to support the Iraq war resolution and her changing positions since then. They point out that, like most of her colleagues, she neglected to read the classified (and more skeptical) version of the National Intelligence Estimate on Iraq's weapons of mass destruction before casting her vote. They note, too, that while she has often and rightly denounced President Bush for deceiving the world when he vowed that war would be a "last resort," she voted against Sen. Carl Levin's amendment to enforce that promise. They charge her with credulity in accepting White House assertions about WMD and Saddam Hussein's connections with al-Qaida -- a fair assessment that nevertheless sounds odd coming from former colleagues of Judith Miller.

What is missing from both of these books is a sufficient appreciation for the political context of Bill and Hillary Clinton's first appearance on the national stage. Rising from obscurity and entering the White House in an era of conservative domination, they were forced to wage guerrilla warfare: sometimes losing, sometimes winning and, despite all their mistakes, notching achievements that look better and better in contrast to the disasters of the Bush years.

But that time is past, and we can hope that the elections of 2006 and 2008 will someday be seen as the transition to a very different and better future. The test for Hillary Clinton is whether she possesses the principle and vision to lead America there.

Shares