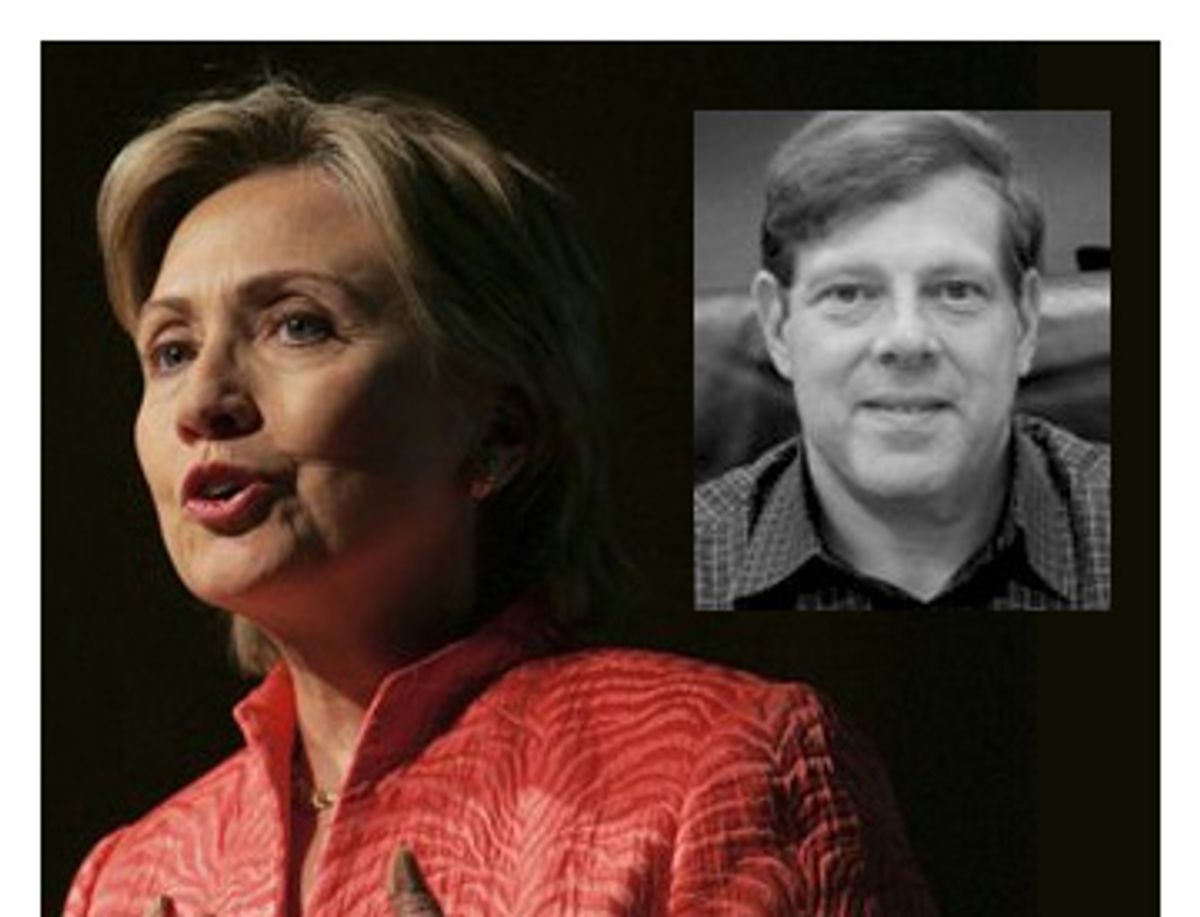

There must be moments when the leaders of America's labor movement mutter the dark lament of the late Rodney Dangerfield, because so often they "get no respect" from the same Democratic politicians who depend on union endorsements and funding. This week they could certainly feel that way, after voicing their "concern" over the actions of a huge union-busting public relations company headed by Sen. Hillary Clinton's top political strategist, Mark Penn -- and getting no satisfactory response.

The prodigious Penn, a pollster and counselor to the Clintons since 1995, has risen to the commanding heights of the public relations and research business over the three decades since he entered politics. Having started in a tiny, two-man polling operation in a New York City mayoral campaign, he is now the CEO of Burson-Marsteller Inc., one of the planet's largest P.R. shops, with corporate clients ranging from Microsoft to Shell Oil and Pfizer. For progressive voters, those connections should raise questions about Penn's dominant role in the Clinton campaign, especially because he has reportedly boasted about the business benefits of his political power.

Smart, skillful and tenacious, Penn is also the ultimate expression of a long-standing trend among political consultants -- that is, claiming to serve the public interest during election years while selling their connections and knowledge to special interests every year. For him and many of his colleagues, the affluence that accrues to influence shapes their attitudes (and their advice to candidates). They tend to reject populism and almost any position that might lead to conflict with their corporate benefactors.

The problem with Penn came to a head over the past few weeks when reporter Ari Berman explored his career and the unsavory history of Burson-Marsteller in the pages of the Nation, including themes that had previously been raised by Mark Schmitt in the American Prospect. (Here I should disclose that I am the director of the Nation Institute Investigative Fund, which provided research support for Berman's article.)

Among the most controversial aspects of Penn's firm's business, from the liberal perspective at least, come under the category of "labor relations," a traditional euphemism for suppressing workers and thwarting their right to organize. Before Penn scrubbed his firm's Web site, it advertised this specialty and noted the firm's capacity to confront "Organized Labor's coordinated campaigns whether they are in conjunction with organizing or contract negotiating." Not the most graceful wording, but the idea is clear enough.

And in practice, as Berman reported, Burson executives have used these skills against two major unions seeking to organize workers at Cintas, the nationwide uniform-supply company, which may be the single most ambitious union drive in North America today.

So here was a conflict of interest that seemed both direct and salient. Sen. Clinton is a declared supporter of labor rights who often tells workers that she is on their side. Besides, she badly wants the support of the Teamsters and UNITE HERE, the unions seeking to organize the Cintas employees, not to mention all the other labor organizations that might help her win the nomination and the presidency. But on the issue of workers rights, her top advisor has been on the other side.

Or has he? Penn said that he had nothing to do with the Cintas account, even though he is Burson's CEO. Moreover, he took offense at the implication that he might be anti-union. He recalled that his father had helped to organize the poultry workers union in Queens, N.Y., where he grew up. Unsurprisingly, his indignation and sentimentality did little to persuade union officials of his sincerity. They know very well that Penn is among the leading figures in the Democratic Leadership Council, whose budget is underwritten by major corporations and whose policies favor business over labor. Even the lunchboxes at DLC conferences display corporate logos.

On June 6, in response to Berman's story, Teamster president James Hoffa and UNITE HERE president Bruce Raynor sent a letter to Clinton about Penn, expressing their "distress" over his firm's role in "the effort to undermine workers right to organize at Cintas, a campaign our unions are involved in, [which] is particularly disheartening." Their letter went on to say that they "do not want to see you or the Democratic Party embarrassed. We look forward to hearing back from you on this matter." Other labor leaders, such as AFL-CIO president John Sweeney and Service Employees International Union president Andrew Stern, have privately told the Clinton campaign of their misgivings about Penn.

Whatever Hoffa, Raynor and their colleagues may have wanted to hear, it is hard to imagine they were satisfied with the Clinton campaign's response via Penn. Essentially, he replied that he hadn't done anything against labor. He didn't step down from his executive position at Burson (as even Karl Rove did in 1999 when he sold his consulting firm to work for George W. Bush's presidential campaign), not even temporarily. He certainly didn't order Burson to cease all union-busting activities. He merely "recused" himself from work on the Cintas account, which he insisted he had never worked on anyway, citing a convenient "conscience clause" available to all Burson executives who might find a particular account morally repugnant. (It isn't clear whether activating the conscience clause means giving up a share of revenues derived from the repulsive activities, or merely bestowing a patina of moral hygiene on the dirty money.)

In fairness to Penn, his friends say that he was "hurt" by the stories linking him to his company's anti-union consulting; and he says that he feels "strong personal sympathy" toward labor. How he squares that with serving as CEO of a union-busting P.R. firm only he can explain.

Meanwhile, the labor leaders have done little to register their outrage at this brushoff. The UNITE HERE and Teamsters Web sites feature heart-rending stories about the abusive and dangerous working conditions at Cintas, where a Tulsa, Okla., laundry worker was killed horribly last March when a conveyor belt dragged him into a superheated dryer. But neither site includes a word about the Penn controversy or the union presidents' letter to Clinton. Evidently the labor leaders don't think their members need to know about this issue (unless they happen to read the New York Times, which covered the matter in its June 5 edition).

Obviously Penn and Clinton felt no fear in blowing them off, assuming that they would retreat without demanding satisfaction. Unless and until labor worries more about demanding loyalty from its supposed friends -- and less about embarrassing sometime political allies -- both its leaders and its members, and those it seeks to represent, will keep getting the Dangerfield treatment.

Shares