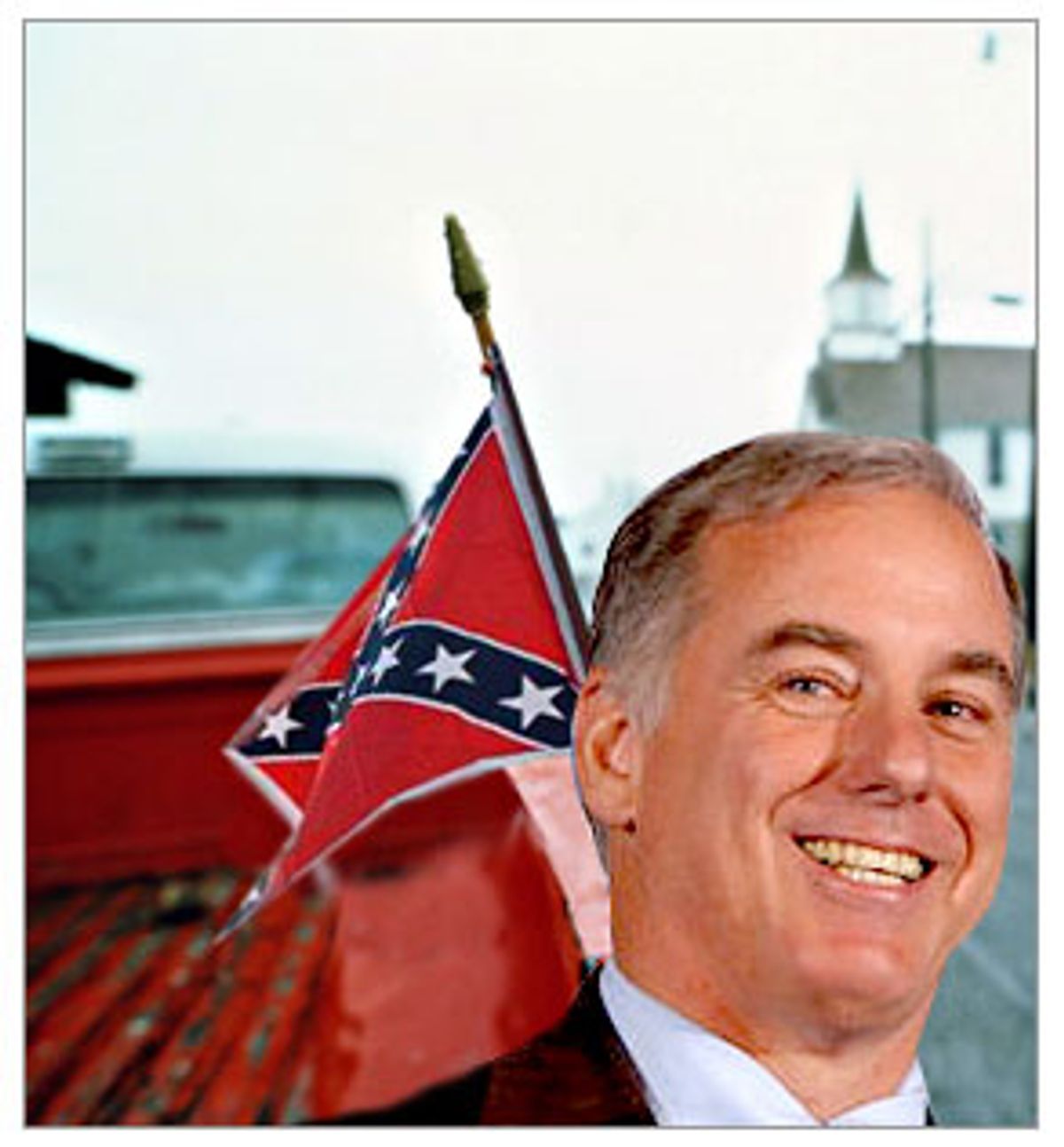

The contest for the Democratic presidential nomination was consumed last week in a storm over a symbol of the past, when Howard Dean told reporters that he wanted "to be the candidate for guys with Confederate flags in their pickup trucks." As with many so-called gaffes, his comment pointed to a larger and obvious political truth. It is that the Democratic and Republican parties have traded places after decades of struggle over civil rights. The solid South of the old Confederacy that once voted uniformly for the Democrats is now the bastion of the Republicans.

From the beginning of the Democratic Party, through the Civil War and even through the New Deal, the South was the foundation stone of the party's national strength. With the coming of the civil rights revolution, Democratic presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson deployed the federal government to support social equality. In reaction, Republicans -- from Barry Goldwater to Richard Nixon to Ronald Reagan -- developed a Southern strategy to win over white voters in the region who felt betrayed. That strategy involved using widely understood code words going back to the Civil War like "states' rights," an updating of the well-worn strategy of Southern reactionaries to demagogue on race in order to keep poor and working-class whites divided from blacks on issues of common interest. Thus the party of Lincoln became the party of Reagan.

Dean, the former Vermont governor, raised in New York City, is the most distinctly old-line Yankee to emerge to prominence within the Democratic Party in living memory. His frontrunner status presents a potential challenge to the first conservative Southern president in modern American history. Despite his New England pedigree, George W. Bush is a man of the Republican South. The possible confrontation reflects deeper polarizations of race, class and society that are driving the country apart.

Dean's error was to evoke the divisive Confederate symbol, hated by blacks as standing for slavery and still upheld by many Southern conservatives as representing their "heritage," but without explaining his reasoning. Shorthand is a common vice of candidates. In March, Dean described his thinking more fully: "I think the Republicans, ever since 1968, with Richard Nixon's Southern strategy, have divided us on race issues. Look, when I go to the South, I talk about race deliberately ... If we're going to have elections about race, we might as well talk about it openly. I want white males, particularly in the South, to come back to the Democratic Party. And the case that FDR made was, look, when was the last time you all got a raise? When was the last time your kids got decent health insurance? What kind of schools do your kids go to if you can't afford a private academy?"

This time Dean left off the filigree of Nixon and Roosevelt. And precisely because Dean is now the frontrunner, the other Democratic primary candidates leaped to create a controversy out of his truncated version, implying that he is racist. The immediate subtext was to stop Dean's momentum.

For days after his gaffe Dean engaged in the etiquette of fulsome apologies. He began by condemning the Confederate flag as "a painful symbol," then asked for forgiveness from "any people in the South who thought they were being stereotyped." A day later he calling his language "clumsy," and added, "I deeply regret the pain that I may have caused." He concluded by portraying the gaffe as a personality flaw: "Now, unfortunately, we all know that nobody's personality is perfect. So the things that make me a strong candidate are also my Achilles' heel." An overdue discussion of the Republicans' Southern strategy was replaced by bowing and scraping.

Dean's Confederate flag problem arose at the same moment as CBS's crisis over broadcasting its highly publicized miniseries titled "The Reagans." The intersection was less odd than it might seem at first; they were both episodes that involved the political volatility of what Bush has called "revisionist history." Ronald Reagan and the Confederate flag, after all, have long been for the Southern Republican Party the equivalent of apple pie and motherhood.

"The Reagans" is the latest in a long line of cheesy TV productions mangling the lives of the presidents, especially the Kennedys, though no one has chosen to politicize these tabloid productions until now. Partly because James Brolin, the husband of Barbra Streisand, a liberal hate figure for the right, was cast as Reagan, the Republican National Committee was aroused. The TV series became an easy target of opportunity to strike against the "Hollywood elite" as unpatriotic in its depiction of the beloved, stricken conservative icon.

Once a Republican mole filched a copy of the script, the Republican Party chairman, Ed Gillespie (former chief lobbyist for Enron), assumed the disinterested pose of historian. The owl of Minerva perched on his shoulder, he called on CBS to yank the series or put a warning on the screen that would flash every 10 minutes that it was make-believe. (The script put words into the mouth of Reagan/Brolin about AIDS sufferers: "They that live in sin shall die in sin." In fact, Reagan said, "Maybe the Lord brought down this plague," because "illicit sex is against the Ten Commandments.") CBS promptly crumpled before the pressure campaign, pulling the show from the network schedule and assigning it to Viacom's cable channel Showtime. Leslie Moonves, the CBS president, abased himself with ritual abject apologies. In the battle for control of imagery, CBS was no match for the RNC. The Republicans know far better than a network the ruthless business of going negative.

"The Reagans," from leaked excerpts of the script, features a distracted Ronnie and harridan Nancy, a melding of 1950s situation comedy, starring the hapless but lovable dad, and the campy 1970s Grand Guignol of "Mommy Dearest." Policy and politics are not its centerpieces.

Certain crucial events in the rise of Ronald Reagan are noticeably missing. His actual words on race and civil rights, essential to his political success, are absent, though the RNC chairman has not complained about that.

Consider just a few true-life scenes that never made "The Reagans": Reagan opposed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, opposed the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (calling it "humiliating to the South"), and ran for governor of California in 1966 promising to wipe the Fair Housing Act off the books. "If an individual wants to discriminate against Negroes or others in selling or renting his house," Reagan said, "he has a right to do so."

After the Republican Convention in 1980, Reagan traveled to the county fair in Neshoba, Miss., where, in 1964, three Freedom Riders had been slain by the Ku Klux Klan. His appearance there was urged and planned by a young congressman named Trent Lott, who had switched from the Democratic to the Republican Party. Before an all-white crowd of tens of thousands, Reagan declared, "I believe in states' rights" -- the code words that were used in the Civil War to justify slavery and the secession of the Southern states from the Union. These words are at the center of the bloody conflict through American history over the essential idea of the United States.

As president, Reagan put his Justice Department on the side of segregation, supporting the fundamentalist Bob Jones University in its case seeking federal funds for institutions that discriminate on the basis of race. In 1983, when the Supreme Court decided against Bob Jones, Reagan, under fire from his right in the aftermath, gutted the Civil Rights Commission.

Reagan consolidated the Southern strategy that Richard Nixon formulated in response to the civil rights movement. This Republican Party has created the radically conservative Southern presidency of George W. Bush. Another scene: When Bush's candidacy was threatened in the Republican primaries of 2000, he rescued himself by appearing at Bob Jones University and wrapping himself in support of the preservation of the Confederate emblem on the South Carolina state flag.

Dean's remarks were awkward, but his challenge to the Republican Party's basic character and the need for a strategy for defeating it will inevitably be revisited by whoever becomes the Democratic nominee, if that nominee cares about winning.

Consider yet another scene: On the day before Dean's last apology, Haley Barbour, the former chairman of the Republican National Committee and the third biggest lobbyist in Washington, was elected governor of Mississippi. He had campaigned at an event sponsored by the Council of Conservative Citizens, an overtly racist group and successor organization to the White Citizens' Council that led opposition to civil rights in the 1960s. In his lapel Barbour wore a pin of the Mississippi state flag, a matter of controversy because of its incorporation of the Confederate flag. On election night, even before he was announced as the winner, Barbour received a congratulatory telephone call from George W. Bush. Look away, Dixieland.

As the great novelist William Faulkner, of Mississippi, wrote: "The past is not dead. In fact, it's not even past."

Shares