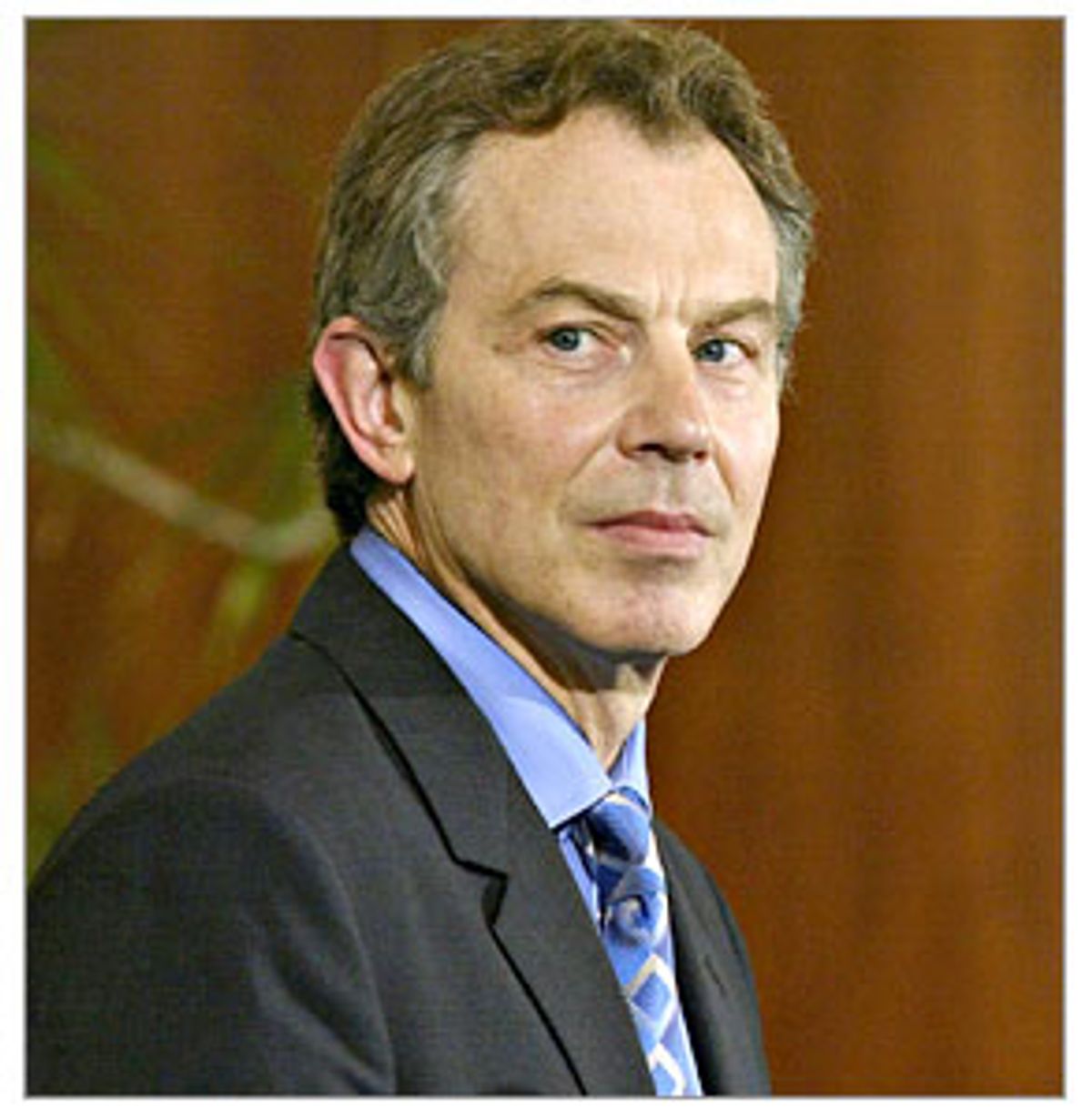

Tony Blair, about to welcome George W. Bush to London for a state visit on Nov. 18 with pomp and circumstance, has assumed the mantle of tutor to the unlearned American president -- a pedagogical role that defines the latest phase of the hallowed special relationship.

Bush originally came to Blair determined to go to war in Iraq, but without a strategy. Blair instructed him that the casus belli was Saddam Hussein's weapons of mass destruction, urged him to make the case before the United Nations, and when the effort to obtain a U.N. resolution failed, persuaded Bush to revive the Middle East peace process between Israel and Palestine that Bush had abandoned. The new "road map" for peace there was the principal concession that Blair wrested from Bush. Blair argued that renewing the negotiations was essential to the long-term credibility of the coalition goals in Iraq and the whole region. But within the councils of the Bush administration that initiative was systematically undermined. Now Blair welcomes a president who has taught him a lesson in statecraft he refuses to acknowledge.

Flynt Leverett, a former CIA analyst, revealed to me that the text of the road map was ready to be made public before the end of 2002: "We had made high-level commitments to key European and Arab allies. The White House lost its nerve. It took Blair to get Bush to put it out. But even then the administration wasn't really committed to it." Leverett is also a former senior director for Middle East affairs at the National Security Council, one of the authors of the road map, and now a fellow at the Saban Center for Middle East Policy at the Brookings Institution. "We needed to work this issue hard, but because we didn't want to make life difficult with Ariel Sharon, we undercut our credibility."

In the internal struggle over peace in the Middle East, the neoconservatives within the administration prevailed. Elliott Abrams, chief of Middle East affairs at the National Security Council, was their point man. During the Iran-contra scandal of the Reagan presidency, Abrams was a player in setting up a rogue foreign policy operation as the assistant secretary of state for Latin America. His solicitation of $10 million from the sultan of Brunei for the illegal enterprise turned farcical when he transposed numbers on a Swiss bank account and lost the money. He wound up pleading guilty to lying to the Congress and was eventually pardoned by former President Bush. He spent his purgatory as the director of a neoconservative think tank, denouncing the Oslo Accords and arguing that "tomorrow's lobby for Israel has got to be conservative Christians, because there aren't going to be enough Jews to do it." Abrams was rehabilitated when George W. Bush appointed him to the NSC in December 2002.

In his new position, Abrams immediately set to work trying to gut the text of the road map. He was suspicious of the Europeans and British, considering them to be anti-Israel if not inherently anti-Semitic, and spoke vituperatively against them to his colleagues. But working in league with his neoconservative allies in the vice president's office and at the Department of Defense, Abrams was unable to prevent Blair from persuading Bush to issue the road map at last.

The key to the road map's success was U.S. support for Palestinian Prime Minister Abu Mazen, indispensable as a partner for peace, but regarded as a threat by both Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon and Palestinian Authority President Yasser Arafat. At the summit on the road map at Aqaba, Jordan, in June, Bush told Abu Mazen: "God told me to strike at al-Qaida and I struck them, and then he instructed me to strike at Saddam, which I did, and now I am determined to solve the problem in the Middle East. If you help me I will act, and if not, the elections will come and I will have to focus on them." Abu Mazen was scheduled to come to Washington to meet with Bush a month later. For his political survival, he desperately required U.S. pressure on the Sharon government to make concessions on building settlements on the West Bank. Abu Mazen sent a secret emissary to the White House: Khalil Shakaki. He is the director of the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research, the only independent Palestinian institute of its kind, which was physically destroyed by Arafat's thugs in early July.

I met with Shakaki in Ramallah on the West Bank recently, where he revealed his account of his urgent trip to the White House. There he met with Elliott Abrams and laid out the conditions of Bush's support essential for Abu Mazen's continued existence. Abrams told him, he said, that Bush "couldn't agree to anything" and offered domestic political considerations: Bush's reliance on the religious right, his refusal to offend the American Israel Political Action Committee and the demands of the upcoming election. "Why are you inviting Abu Mazen here?" asked Shakaki. "We're not inviting him," Abrams replied. "He's just here." Shakaki pleaded that the Palestinian was "a window of opportunity" and "an experiment" who could not go on without U.S. help. "He has to show he's capable of doing it himself," Abrams answered dismissively.

Inside the NSC, those in favor of the road map, CIA analysts Flynt Leverett and Ben Miller, among others, were forced out.

On Sept. 6, Abu Mazen resigned, and the road map, for all intents and purposes, collapsed. "We are moving towards hell," Shakaki told me.

Tony Blair gave George W. Bush a reason for the war in Iraq and prompted him to offer a commitment to peace for the Middle East, preventing Bush from appearing as a reckless and isolated leader. In return for his good faith, the teacher's seminar on the Middle East has been dropped. "Just what is it that Blair has influenced?" wonders Leverett.

Harold Macmillan, the postwar prime minister, famously remarked that after empire the British would act toward the Americans as the Greeks to the Romans. Though the Greeks were often tutors to the Romans, Macmillan neglected to mention that the Greeks were slaves.

Shares