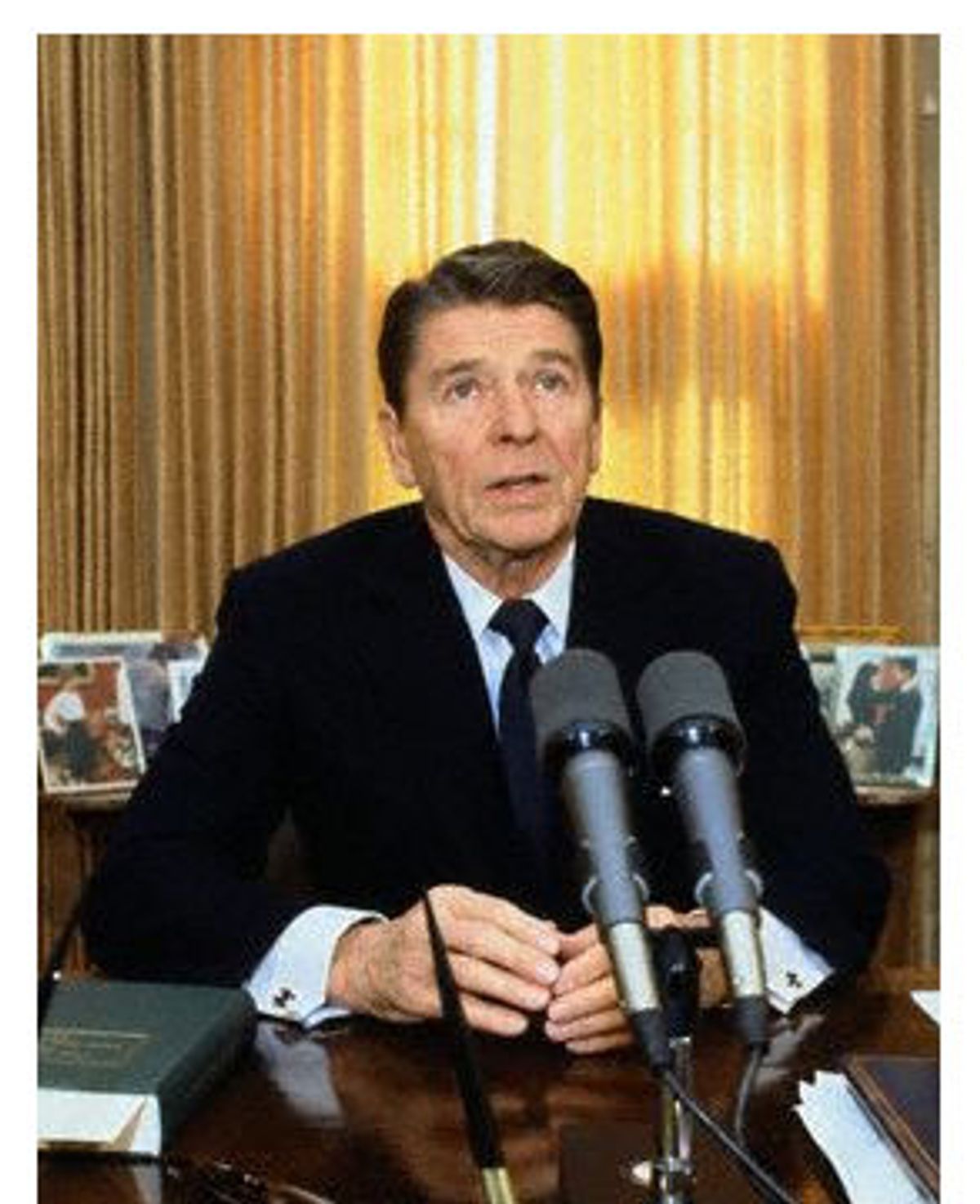

Michael Lind, Whitehead Senior Fellow at the New America Foundation, and the author of "Made in Texas: George W. Bush and the Southern Takeover of American Politics":

The presidency of Ronald Reagan was the Thermidor of the conservative movement that had crystallized around William F. Buckley Jr.'s National Review and found its first political champion in Barry Goldwater. The "movement conservatives" wanted to repeal the New Deal and to replace the Cold War liberal policy of containing the Soviet Union with a more aggressive strategy of "roll-back." On assuming office, Reagan quietly abandoned both goals. Reagan did not risk his popularity by attempting to repeal the major New Deal and Great Society entitlements for the middle class, and he adopted a strategy of containment that represented a continuation of the Truman-Kennedy-Johnson strategy, to which Eisenhower, Nixon and Carter in different ways had offered alternatives.

In vain the conservatives cried, "Let Reagan be Reagan!" But the Ronald Reagan who voted four times for Franklin D. Roosevelt and described FDR as his favorite president was the same man who left Roosevelt's domestic legacy untouched and brought the Cold War to a bloodless end by following Truman's containment policy.

In politics, too, Reagan represented an end, not a beginning. His political base consisted of transplanted Midwesterners like him in California, and he rode to power on the backlash against the Civil Rights Revolution and the counterculture by the white working class and middle class, many of them, like him, former Roosevelt Democrats.

Today's right is profoundly different from Goldwater-Reagan conservatism, though they share a common tactic: Unable to repeal popular liberal programs directly, each has cut taxes to create deficits that might inspire major spending cuts in the future. In this respect, George W. Bush is the heir of Ronald Reagan.

Martin Andersen, President Reagan's domestic and economic policy advisor, 1981-1982:

I think the way to look at Reagan's legacy is to make believe you are a historian 100 years from now, and look back at what happened in the 1980s, when the political dust has settled -- unlike the last 48 hours, when everybody is being nice to everybody. I can't be sure, but I think there will be three things in Reagan's legacy.

First, historians will look at the sweep of history when communism started, spread, and see that it ended on Reagan's watch. He didn't do it himself, but he was the political leader of the free world, and deserves a certain amount of credit.

Second, the threat of an all-out nuclear war between the Soviet Union and the United States went away, an extraordinary thing. Again, he was president of the United States, when the threat ended, the Berlin Wall came down, and he and Gorbachev became buddies, and Gorbachev is coming to the funeral now.

And third, he was president during a period of prosperity that began in 1982. There are a lot of reasons the economy kicked up then; one was tax cuts, and another was the threat of all-out nuclear war fading away. And the early 1980s was the beginning of the computer revolution, which has been an exploding galaxy. These are the three main things.

Things like Iran-Contra might not even be a footnote. All the complaints, they might not be big enough to be part of the Reagan legacy.

John Judis, senior editor for the New Republic:

I lived through Ronald Reagan's two terms as governor of California and his two terms as president, and was forever bewildered by his political success.

Reagan was committed to a very simple-minded and apocalyptic worldview, but he could articulate it in terms (like the vision of America as a "city on a hill" and the Soviet Union as "the evil empire") that resonated with Americans. At the same time, he was a former labor negotiator who loved the give and take of politics and was always willing to compromise when he faced an unyielding majority. He was ideologically dogmatic, but politically flexible and astute.

He entered politics after Goldwater's crushing defeat, but he showed in his 1966 gubernatorial election that conservatives could win voters outside the local chamber of commerce or John Birch Society chapter by appealing to growing social concerns among white working-class Democrats about civil rights and about cultural and political radicalism.

He turned a narrow intellectual movement into a political majority. This new majority was founded in part on hatred and resentment, but Reagan's methods were so subtle that he didn't leave a personal legacy of hatred behind him.

As president, Reagan's record is decidedly mixed.

But Reagan deserves lasting credit for helping to end the Cold War. How much Reagan's aggressive policies and military buildup during his first term contributed to this result remains to be seen; but in 1985, Reagan recognized that the new Soviet Premier Mikhail Gorbachev wanted to take the Soviet Union out of the Cold War.

They also were beginning to wind down the disastrous war in Nicaragua. In Washington in 1988, conservatives were sporting buttons reading, "Support the Contras, Impeach Reagan."

By the time he left office, Reagan's foreign policy enjoyed more support from Democrats than from conservative Republicans. It's well to keep that in mind as George W. Bush and his minions seek to summon Reagan's memory to justify their disastrous policies in Iraq.

Frank Mankiewicz, former president of National Public Radio and press secretary to Sen. Robert Kennedy:

The legacy of Ronald Reagan?

We've been reading these last few days that it was dedication, decency and honesty -- the Wall Street Journal, in a full-page editorial, virtually proposed him for sainthood, or at least that his face appear on every coin and paper currency. But the verdict, of course, will be mixed. Taxes went down and then came back up. Foreign policy included triumphs at the Berlin Wall as well as failures in Afghanistan, and particularly Iran-Contra.

But it seems to me we all have left out an evaluation of the main influence on any legacy Reagan leaves us -- the influence of Hollywood. It was there he not only learned his lines but his characters. Hollywood had mastered, in that Golden Age of the '30s, what Americans want to be told about what kind of people they are as well as what they expect of their heroes, and Ronald Reagan mastered all that, and mastered it well -- the optimism, the candor, the will to win; he was a true role model. In addition, he learned more of Hollywood's values; for example, he and Nancy had many gay friends and never thought about it, and he forever told fanciful stories, and made them seem true, about how racial prejudice had long been banished. I think his legacy, and it is one Americans should think about this week and in the future, is that you could learn more about America on the sets of Warner Bros. than at any state house or in the halls of Congress.

Andrew Cockburn, co-author of "Out of the Ashes: The Resurrection of Saddam Hussein":

Somewhere out there, in one of America's secret jails, a prisoner is mourning the passing of an old friend.

Saddam Hussein may have had his differences with some of our recent chief executives, but when the going got tough, Ronald Reagan was always there for the Iraqi dictator.

The liaison can be dated from the summer of 1982, two years into the bloody Iran-Iraq war. Iraq was losing, with Iranian forces advancing deep into Iraqi territory. Saddam was desperate for help, and he found it at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, where Ronald Reagan decided that Iraq must not be defeated. Almost immediately, despite the fact that Iraq was then on the official list of terrorist nations, U.S. support began flowing to Baghdad, including precursor chemicals for chemical weapons.

The friendship was not without occasional disputes. In 1986, it emerged that Reagan, while aiding Saddam, was also providing assistance to the Iranians. In fact, during a bloody battle on the Fao Peninsula in January that year, both sides were operating with U.S.-supplied intelligence data. Reagan had to apologize to Saddam for two-timing him, make up for it by stepping up assistance to the Iraqi dictator.

There was one last favor for Reagan to bestow on his Baghdad pen pal. After an Iraqi chemical attack slaughtered some 5,000 Kurds in the city of Halabja in March 1988, there were moves both internationally and in Congress to issue protests and sanctions. The Reagan administration quietly stymied all such efforts. That's what friends are for.

In the light of their friendship, it would be only fitting if Saddam, wherever he is, were allowed to join with other world leaders, past and present, in expressing his condolences at the passing of a faithful ally.

Larry Birns, director of the Council on Hemispheric Affairs. COHA research fellow Jessica Leight contributed to his response:

As journalists and Sunday talk show hosts struggle to surpass each other in coining panegyrics for the late President Ronald Reagan, they have hardly touched the Iran-Contra scandal, one of the most significant foreign policy debacles in recent U.S. diplomatic history.

Dismissed by many as a relic of the Cold War era, the Iran-Contra affair in fact represents a crucial -- if at the time almost unnoticed -- portent of foreign policy explosions that would unfold under the tenure of Reagan's ideological heir and reverent protégé George W. Bush. What was later to become reckless aggression in Iraq began under Reagan as the Central American wars of the 1980s, marked by a driven ideology, a contempt for both international organizations and the pesky mechanisms of congressional intent and oversight, and the utter subversion of democratic processes.

The remarkable continuity between the Contra war and Iraq is not merely a coincidence, but rather reflects the return of a host of key players in the Iran-Contra affair, all of whom were discredited in the subsequent investigation by independent counsel Lawrence Walsh.

Elliott Abrams, John Negroponte and Otto Reich, who under the Bush administration have been major figures in the invasion and occupation of Iraq, were key players in sending arms and weapons to the Contras and Central American death squads.

As the funeral procedures continue, analysts and policymakers alike might do well to recall this enormous blemish on Reagan's supposedly "Teflon" record -- and more importantly, with this occasion to take note of the increasing evidence that equally egregious policy lapses in this hemisphere are being implemented by the current administration. The Iran-Contra affair may be in the past, but the dangerous brand of quasi-legal and ideologically driven foreign policy it represents is alive and flourishing.

Steven Hayward, a fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, and the author of "The Age of Reagan: The Fall of the Old Liberal Order, 1964-1980":

Agree or disagree with him, Reagan deserves to be considered alongside Franklin Roosevelt as the most consequential president of the 20th century. Like FDR, Reagan has become the central figure of an era of American life. Just as FDR remade his party and cast a long shadow over the next generation of American political life, Reagan transformed the GOP, and his shadow over our subsequent political course is proving to be similarly long, and may still be lengthening.

He did not achieve all his main objects such as shrinking government. Yet it is a melancholy reflection on the limits of politics that even the greatest and most successful politicians often end their careers with a large note of failure hanging over their head. Lincoln died with the question mark of reconciliation and reconstruction; Woodrow Wilson left office amid the failure of the League of Nations treaty; FDR died, and Churchill left office, with World War II won, but with the seeds of the Cold War clearly germinating. Reagan left office with the Cold War still going, and with astronomical budget deficits that threatened the nation's well-being for as far as the eye could see -- a seemingly long-term legacy of failure.

Yet within a breathtakingly short time, the Cold War was over and the nation's biggest fiscal problem, prior to Sept. 11, was what to do with its budget surpluses. Both events lent a large measure of vindication to Reagan's designs. His huge budget deficits, Lou Cannon has remarked, now look like the wartime deficits of the final campaign of the old war, and therefore as a bargain. Although other leaders at home and abroad deserve their share of the credit for these happy events, it is hard to conceive of their advent without Reagan.

Shares