"We have accepted, so to speak, a second Bill of Rights under which a new basis of security and prosperity can be established for all -- regardless of station, race, or creed." -- Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Next month's Democratic Convention will be held at one of the most remarkable times in American history. After a burst of creativity during the Reagan era, the nation's conservatives are intellectually exhausted. Preoccupied by terrorism and obsessed by tax cuts, Republican leaders have resorted to self-congratulatory displays of patriotism and demonization of their political opponents. For their part, Democrats have an extraordinary opportunity to think ambitiously -- one that they would be wise to seize rather than squander.

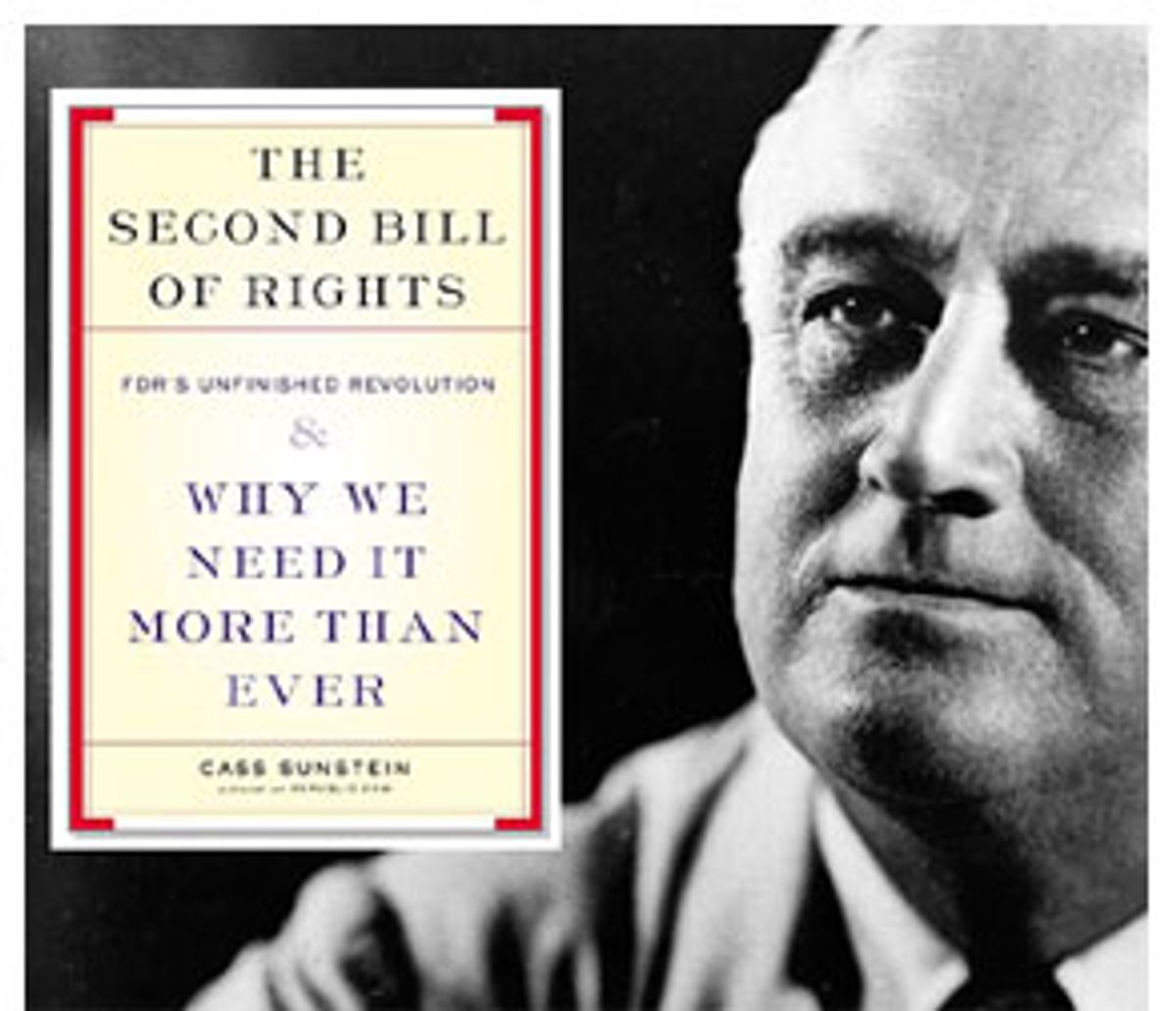

Where might they look? They could do no better than the nation's most important leader in both peace and war, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and, particularly, his most magnificent speech, in which he took threats to national security as the basis for proposing a second Bill of Rights. Roosevelt's proposal, long confined to the dustbin of history, was intended as a kind of 20th century analogue to the Declaration of Independence. The Democratic Party should reclaim it as such, and the convention in Boston would be a perfect time to do it.

(While the current White House seems oblivious to the issues that gave rise to FDR's second Bill of Rights, Iraqi government officials, surprisingly, have included parts of it in Iraq's interim Constitution.)

On Jan. 11, 1944, the war against fascism was going well, and the real question was the nature of the peace. At noon, Roosevelt delivered his State of the Union address to Congress. The speech wasn't elegant. It was messy, sprawling, unruly, a bit of a pastiche and not at all literary. It was the opposite of President Lincoln's tight, poetic Gettysburg Address. But because of what it said, this forgotten address has a strong claim to being the most important speech of the 20th century -- and to defining the deepest aspirations of the Democratic Party.

Roosevelt began by pointedly emphasizing that the war was a shared endeavor in which the United States was simply one participant: "This Nation in the past two years has become an active partner in the world's greatest war against human slavery." And as a result of that partnership, the war was being won. He continued, "But I do not think that any of us Americans can be content with mere survival ... The one supreme objective for the future ... can be summed up in one word: Security." Roosevelt argued that security "means not only physical security which provides safety from attacks by aggressors" but "also economic security, social security, moral security." Roosevelt insisted that "essential to peace is a decent standard of living for all individual men and women and children in all nations. Freedom from fear is eternally linked with freedom from want."

Directly linking international concerns to domestic affairs, Roosevelt emphasized the need for a "realistic tax law -- which will tax all unreasonable profits, both individual and corporate, and reduce the ultimate cost of the war to our sons and daughters." He stressed that the nation "cannot be content, no matter how high the general standard of living may be, if some fraction of our people -- whether it be one-third or one-fifth or one-tenth -- is ill-fed, ill-clothed, ill-housed, and insecure."

At this point Roosevelt became stunningly bold and ambitious. He looked back, not entirely approvingly, to the framing of the U.S. Constitution. At its inception, he said, the nation had grown "under the protection of certain inalienable political rights -- among them the right of free speech, free press, free worship, trial by jury, freedom from unreasonable searches and seizures." But over time, these rights had proved inadequate: "We have come to a clear realization of the fact that true individual freedom cannot exist without economic security and independence ... In our day these economic truths have become accepted as self-evident. We have accepted, so to speak, a second Bill of Rights under which a new basis of security and prosperity can be established for all -- regardless of station, race, or creed."

Then he listed the bill's eight rights:

Roosevelt added that these "rights spell 'security'" -- the "one word" that captured the overriding objective for the future. Recognizing that the second Bill of Rights was continuous with the war effort, he said, "After this war is won, we must be prepared to move forward in the implementation of these rights ... America's own rightful place in the world depends in large part upon how fully these and similar rights have been carried into practice for our citizens. For unless there is security here at home there cannot be lasting peace in the world."

FDR emphasized "the great dangers of 'rightist reaction' in this Nation" and concluded that government should promote security instead of paying heed "to the whining demands of selfish pressure groups who seek to feather their nests while young Americans are dying."

What made it possible for Roosevelt to propose the second Bill of Rights? Part of the answer lies in the recent memory of the Great Depression; part of it lies in the effort to confront the dual threats of fascism and communism with a broader vision of a democratic society. But part of the answer lies in a simple idea, one now lost but pervasive in American culture in Roosevelt's time -- that markets and wealth depend on government intervention. Without government creating and protecting property rights, property itself cannot exist. Even the people who most loudly denounce government interference depend on it every day.

Political scientist Lester Ward vividly expressed the point in 1885: "Those who denounce state intervention are the ones who most frequently and successfully invoke it. The cry of laissez faire mainly goes up from the ones who, if really 'let alone,' would instantly lose their wealth-absorbing power." Think, for example, of the owner of a radio station, a house in the suburbs, an expensive automobile, or a large bank account. Each such owner depends on the protection provided by a coercive and well-funded state -- equipped with a police force, judges, prosecutors, and an extensive body of criminal and civil law.

From the beginning, Roosevelt's White House understood all this quite well. In accepting the Democratic nomination in 1932, Roosevelt insisted that we "must lay hold of the fact that economic laws are not made by nature. They are made by human beings." Or consider Roosevelt's address to the Commonwealth Club in the same year, where he emphasized "that the exercise of ... property rights might so interfere with the rights of the individual that the government, without whose assistance the property rights could not exist, must intervene, not to destroy individualism but to protect it."

Thus, against the backdrop of the Depression and the threats from fascism and communism, Roosevelt was entirely prepared to insist that government should protect individualism not only by protecting property rights but also by ensuring decent opportunities and minimal security for all. In fact, this was the defining theme of his presidency. When campaigning against Herbert Hoover in 1932, Roosevelt called for "the development of an economic declaration of rights, an economic constitutional order" that would recognize that every person has "a right to make a comfortable living."

Extending this theme to the international arena in his State of the Union address in 1941, Roosevelt endorsed the "four freedoms" -- freedom of speech, freedom of religion, freedom from want, and freedom from fear -- that, he said, must be enjoyed "everywhere in the world." As the Allied victory loomed on the horizon, Roosevelt offered details about "freedom from want" in his speech proposing a second Bill of Rights.

Roosevelt died within 15 months of delivering this great speech, and he was unable to take serious steps toward implementing the second bill. But his proposal, despite being mostly unknown in the United States, has had an extraordinary influence internationally. It played a major role in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, finalized in 1948 under the leadership of Eleanor Roosevelt and publicly endorsed by the leaders of many nations, including the United States, at the time. The declaration proclaims that everyone has a "right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control." The declaration also proclaims a right to education.

By virtue of its effect on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the second Bill of Rights has been a leading American export -- influencing the constitutions of dozens of nations. The most stunning example is the interim Iraqi Constitution, written with American help and celebrated by the Bush administration. In Article XIV, it proclaims: "The individual has the right to security, education, health care, and social security," adding that the nation and its government "shall strive to provide prosperity and employment opportunities to the people."

In the 1950s and 1960s, the Supreme Court embarked on a path of giving constitutional recognition to some of the rights that Roosevelt listed. In Rooseveltian fashion, the court suggested that there might be some kind of right to an education; it ruled that people could not be deprived of welfare benefits without a hearing; it said that citizens from one state could not be subject to "waiting periods" that deprived them of financial and medical help in another state. And in its most dramatic statement, the court said: "Welfare, by meeting the basic demands of subsistence, can help bring within the reach of the poor the same opportunities that are available to others to participate meaningfully in the life of the community. [Public] assistance, then, is not mere charity, but a means to 'promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity.'"

By the late 1960s, respected constitutional experts thought the court might be on the verge of recognizing a right to be free from desperate conditions -- a right that captures many of the rights that Roosevelt attempted to implement. But all this was undone as a result of the election of Richard Nixon as president. Nixon promptly appointed four Supreme Court justices -- Warren Burger, William Rehnquist, Lewis Powell and Harry Blackmun -- who showed no interest in the second Bill of Rights. In a series of decisions, the new justices, joined by one or two others, rejected the claim that the Constitution protected the rights that Roosevelt listed (a vivid reminder of how much the interpretation of the Constitution depends on the outcome of presidential elections).

Roosevelt himself did not argue for constitutional change. He wanted the second bill to be part of the nation's deepest commitments, to be recognized and vindicated by the public, not by federal judges, whom he distrusted. He thought it should be seen in the same way as the Declaration of Independence -- as a statement of America's most fundamental aspirations.

The United States continues to live, at least some of the time, according Roosevelt's vision. A national consensus exists in favor of the right to education, the right to social security, the right to be free from monopoly, possibly even the right to a job. But under the influence of powerful private groups -- the "rightist reaction" against which Roosevelt specifically warned -- many of Roosevelt's hopes remain unfulfilled. In recent years, many Americans have embraced a confused and pernicious form of individualism that endorses rights of private property and freedom of contract, and respects political liberty, but distrusts government intervention and believes that people must largely fend for themselves.

Democrats so far have not adequately responded to this approach through words or deeds. They have failed to show, as Roosevelt did, that this form of so-called individualism is incoherent. As Roosevelt well knew, no one is really against government intervention, whatever they say. The wealthy, at least as much as the poor, receive help from government and from the benefits that it bestows.

It is especially unfortunate that Democrats have failed to respond to the rebirth of this confusion under the current administration. While proposing a sensible system of federal tax credits to increase health insurance coverage, for example, Bush found it necessary to make the senseless suggestion that what he had proposed was "not a government program." Time and again, conservatives claim that American culture is antagonistic to "positive rights," even though property rights themselves require "positive" action.

The result? Both at home and abroad, we have seen the rise of a false and utterly ahistorical picture of American culture and history. That picture is far from innocuous. America's self-image -- our sense of ourselves -- has a significant impact on what we actually do. We should not look at ourselves through a distorted mirror, lest we remold ourselves in its image.

Amid the war on terrorism, the problem goes even deeper. The nation could have taken the attacks of 9/11 as the basis for a new recognition of human vulnerability and of collective responsibilities to those who need help. It was the threat from abroad, after all, that led Roosevelt to a renewed emphasis on the importance of security -- with the understanding that this term included not merely protection against bullets and bombs but also against hunger, disease, illiteracy and desperate poverty. Hence Roosevelt supported a strongly progressive income tax aimed at "unreasonable profits" and offering help for those at the bottom. President Bush, on the other hand, has supported tax cuts that give disproportionate help to those at the top. Most important, Roosevelt saw the external threats as a reason to broaden the class of rights enjoyed by those at home. Bush, to say the least, has failed to do the same.

President Bush, like America as a whole, has been celebrating what is called the "Greatest Generation," the victors in World War II. But that celebration has been far too sentimental; it has betrayed the pragmatic and forward-looking character of that generation. Meeting in Boston, the birthplace of the American Revolution, the Democratic Party has a unique opportunity to reclaim Roosevelt's legacy -- to remind itself, and the nation, that the leader of the Greatest Generation had a project, one he believed to be radically incomplete. Affirming the second Bill of Rights would be an excellent place to start.

Shares