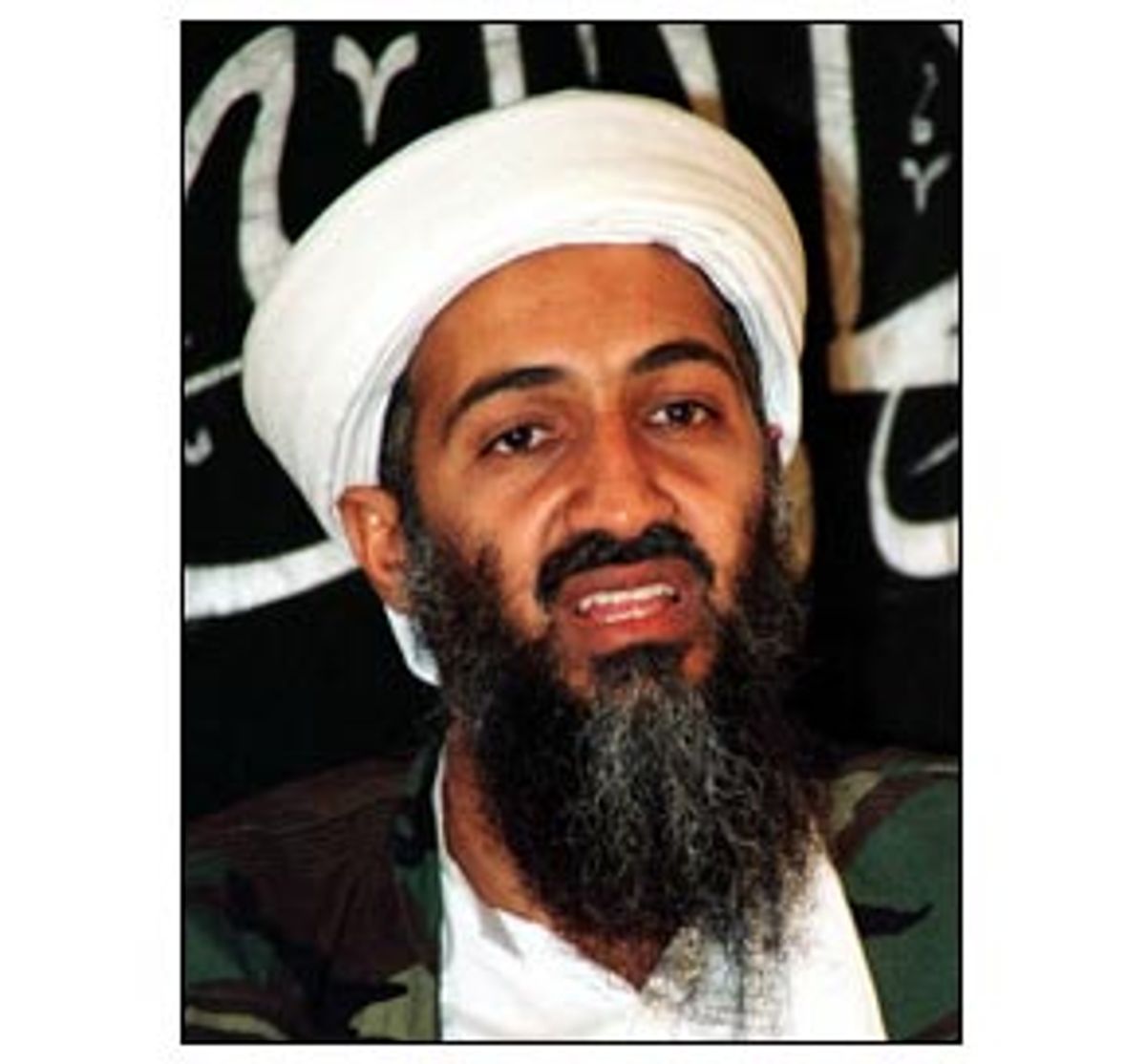

The White House now says that, in addition to everything else, Sept. 11 wrecked our economy. Bush may be the "no-jobs president," but Osama bin Laden is to blame. Let's look at the evidence.

The chart shows that "W" entered office on a rough note. Real GDP growth had already slumped in the summer and fall of 2000. It bounced on the edge of recession for several quarters and then fell into one in the third quarter. Much of that, no doubt, came in the three weeks following Sept. 11. (I've always said Bush should get a pass for his first year.)

In the fourth quarter beginning on Oct. 1, 2001, investment collapsed. But the overall economy did not. Instead, it rebounded. Why? Tax rebates went out, interest rates fell and automakers (among others) cut their prices. Auto and home sales soared. Federal government spending also surged -- on reconstruction, homeland security and the military. The stock market had recovered almost all its losses by year's end.

And we went to war. After our quick "victory" in Afghanistan investment surged, but only for one quarter. After that, growth fell off as household and government spending faded away. This was the second loop of the "W" slump. Indeed, we nearly slipped back into full recession at the end of 2002. That fact could have cost the Republicans at the polls in the midterm elections had the electorate been focused on it, but the voters were distracted. From September 2002 until its launch, we were engaged in the run-up to the war in Iraq.

And when that war came, the "Afghan" economic pattern repeated on a larger scale. Federal military spending added almost 1.5 points to growth in the second quarter of 2003, kicking an anemic growth rate above 4 percent for the first time under Bush's rule. Then, in the rush of the Baghdad "cakewalk," the economy finally fired on all cylinders at once. Consumption and investment both jumped, pushing the growth rate to 7.4 percent in the third quarter of 2003.

That was the peak, the top of the Bush economy. It has been downhill since then. In the second quarter of 2004, consumer spending contributed only 1.1 points to growth. The investment surge still had some spark to it, contributing 2.6 points. But every sign so far suggests that the third quarter of 2004 will be worse on both fronts. Meanwhile, the contribution of government spending to the growth rate has fallen to half a percent overall.

So what went wrong? Why did we lose so many jobs and never get them back? Yes, Bush inherited a weakening economy. Yes, jobs were lost after Sept. 11. But the key is that they didn't come back in spite of two bouts of supposedly good news: the aborted start of a recovery in 2002 and the now-fading start of a real recovery in mid-2003.

Jobs were lost, in the main, because of a deep slump in business investment, which fell almost 10 percent between 2000 and 2003. Some of that happened before 9/11. Much of it happened immediately afterward. And then we lumbered on for a year and a half during which investment contributed nothing to growth and in consequence nothing to jobs.

Was all of that due to 9/11? Did the bin Laden effect last for two years? If it did, one reason is that Bush failed to finish the Afghan war. Soon after bin Laden escaped at Tora Bora, the Special Forces were diverted to Iraq. But there is a larger issue. What could Bush have done to help the economy that he did not do?

First, he didn't change his tax program. Bush's focus remained on cutting taxes for the wealthy in the long term. Congress had added some "stimulus" measures in 2001 and again in 2003, which boosted consumption and total spending for short periods. But they didn't create jobs -- a lesson for future Keynesians seeking cheap solutions. The long-term tax cuts to which they were coupled also failed to ignite business investment and job creation.

The tax cuts meant that other vitally important things could not be done. In particular, states and cities, once a mainstay of growth (contributing an average of almost half a point to the GDP every quarter from 1997 through 1999), have since the end of 2001 contributed just a little more than a tenth of a point per quarter. Under Bush, states and localities have been strapped -- and the federal government hasn't helped them out.

And then we went to war, and found that war fever is not very good for jobs. The seemingly quick victory in Afghanistan led to an investment jump in the following quarter, but the effect was small and quickly evaporated.

The war in Iraq raised total government spending by much more. When it appeared to end in swift victory, the effect, at first, was galvanic. Investment surged (alongside consumption), adding three points to growth in the third quarter of 2003. Within a few months employment started to grow as well. In the year since, we have gained about a million jobs. That's about half of those lost, about a third of what the administration's economists thought they'd get -- and about a fifth of what would restore full employment.

But all that happened when people thought the war was over. Now it's clear that the war isn't over. It's clear that we didn't win it when Bush declared, "Mission accomplished." In fact, it's obvious that we aren't winning it now. And it looks like this phase of rising investment, too, is fading again.

What's the missing ingredient? Here's a wild guess: optimism. Vision. A sense of direction. Perhaps even leadership. A truly sustained investment boom requires optimism. It requires confidence, among other things, that peace, stability, growth, development and strong markets will be there in six months' or a year's time. To an extent few appreciate, our economy runs on imagination.

More than any other nation on earth, we have to create the future's business, and with it the jobs of the future. That means we have to think through what they are. As with the long buildup to the Internet boom, we must come to believe, as a community, that the future will take some particular shape. Only then will private investors put up the money. This is hard work, easy to get wrong. And a nasty war has gotten in the way. A war can have an insidious effect on the national ability to think. (It can also impair key calculations such as the future of oil prices.) Peace and prosperity are associated in economic history, for good reason.

So long as we're stuck in Iraq, bleeding harder every day (and building toward crises with Iran and North Korea), I bet against a strong and long revival of private business investment. That means I also bet against strong and sustained growth of decent jobs, and against a return to full employment. And I'd keep to that bet even in the face of new stimulus measures, such as new tax cuts or making the old ones permanent.

If I'm right, a long weakness in private investment could be the largest economic cost of the Iraq war. More important than what the war has taken from the budget is the confidence it may have ripped from the heart and soul of American business, from investors' willingness to gamble, big time, on our future at home.

It's a fair point that Osama bin Laden hit us hard. The war against him, in Afghanistan, was a necessary evil. Moreover, war helps the growth rate -- as Bush's wars have twice confirmed. But on a deeper level, war is bad for business. And it's terrible for jobs.

Unfortunately for Bush, the important war as it affects our economy isn't the one in Afghanistan. It's the one in Iraq. The economic issue isn't the wound inflicted by al-Qaida. Three years after 9/11, bin Laden isn't to blame for where we stand now. Bush is. "W," after all, stands for "wreckless."

Shares