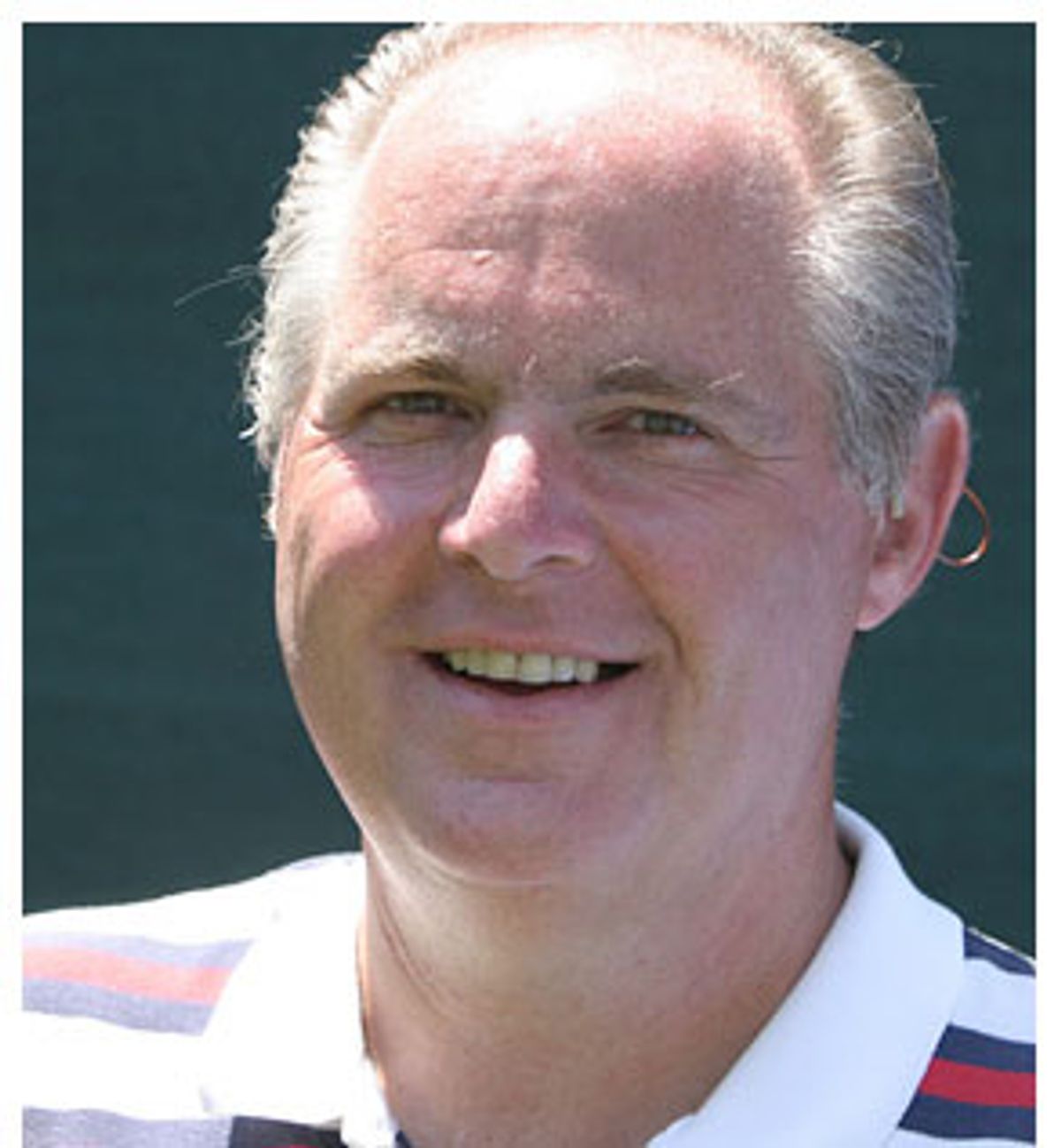

When I was 12 years old, I was Rush Limbaugh's biggest fan. Every day, my father and I listened to him for hours. "Mega-dittos" -- Limbaugh's catchphrase -- was part of my childhood vocabulary, and Limbaugh was the hero who fought for my father's values. Until recently, my dad was still an avid listener.

In mid-May, I played an Iraqi prisoner in the opening night of the play "Abu Ghraib," an original student production at Harvard University, where I am a master's candidate in ethics. My father called to wish me luck. Imagine his disappointment when I told him what Limbaugh had said about me in his radio program that day:

"Here you have these dunces ... at Harvard now doing a playing on the travesties of Abu Ghraib, and you know this is going to get back to the people in Baghdad, the insurgents and this sort of thing. It's just typical. These people hate the country, folks. I'm telling you: There's an anti-American bias in the American left."

My dad, who has voted Republican all his life, was shocked. "But this is beyond partisan politics!" he said. "Has he seen the play?"

No, and Limbaugh still has not seen the show. Neither, for that matter, have the dozens of others who have sent those of us involved in the play hate mail. Nor has Bill O'Reilly, who lambasted the play on his television program -- for both its subject matter and because the university did not permit his film crew to tape the show. He attacked the play as "creepy" and called us stupid, anti-American college kids who have something to hide. He conveniently failed to mention that we couldn't allow an outside organization to tape the show because of standard university policy. O'Reilly has used this supposed injustice against him to focus media attention on him and his false claims and away from the real injustices presented in the play.

So they have all missed the point: The play is an attempt to humanize every prisoner and soldier at Abu Ghraib, and to speak to the tragedy that occurred there. It is in no way about anti-Americanism or Republicans vs. Democrats. It's about a problem that concerns all of us. The play's director and producer turned down an invitation to appear on O'Reilly's show for just that reason -- this is not a partisan issue.

"Abu Ghraib," written and directed by Harvard sophomore Currun Singh and performed by 15 students, opened to four sold-out audiences on May 12. The 90-minute play examines prisoner abuse through testimony, drama, modern dance and film. The stories it tells are factual accounts -- of a soldier whose friends were killed in war, of an insurgent filled with hatred for Americans, of the sergeant who turned in the incriminating photographs from Abu Ghraib.

My character is based on a real Iraqi prisoner, Huda Alazawi, arrested by American soldiers in December 2003 after she inquired after her missing brother. They detained her at Abu Ghraib overnight, and in the morning they threw his dead body at her feet.

In the play, Alazawi finds in herself a rage that reveals her own capacity to torture others, in the same way her abusers directed their rage at her. I am not an actor, and I do not claim to have any privileged understanding of what Alazawi went through. But like many of us, I felt distress after an encounter with cruelty, and the experience inspired me to take part in the Harvard show.

At the Republican National Convention last fall, I was part of a crowd arrested by New York Police Department officers without warning. When the plastic handcuffs sliced deep into my wrists, I asked a lieutenant to loosen them. He looked straight into my eyes, grabbed my wrists and hands, and twisted them hard. I fell into sobs as he walked away. Through 16 hours of detention, the police berated us, whistled circus tunes at us, and denied us legal counsel. Several months later, my charge of disorderly conduct was dismissed.

What happened to Alazawi and what happened to me are profoundly different. But some crucial elements, in the broadest terms, are the same: the uniformed man, the woman in handcuffs, and the body that is violated. Both prisoner and officer are human beings placed in tragic circumstances, often outside their control; they're caught in a cycle of violence and hatred that must stop.

If I care about our soldiers, what they are called to do, and the pressures that are breaking them -- if I recognize the injustice that has taken place and call it for what it is -- does that really mean I "hate the country"? If news about this play gets "back to the people in Baghdad," will it cause more violence? Or will our recognition of American wrongdoing suggest the possibility of reconciliation?

On the other hand, Limbaugh has called the torture at Abu Ghraib no different from what happens at a college initiation. He has compared it to a Britney Spears concert. And he has defended it by saying that the soldiers involved needed emotional release.

If he stepped off his conservative platform for a moment, perhaps Limbaugh would see that Americans cannot simply shrug off Abu Ghraib. And to respond to the tragedy, we must first recognize the stories of the victims and perpetrators, some of which are told in the play. We must accept that state-sponsored abuse can happen to anyone, anywhere, not just to prisoners in Iraq.

My father has stopped trusting Limbaugh because he knows his daughter does not hate America. But I don't want to give up on Rush. The cast of "Abu Ghraib" is happy to extend an invitation to him and Bill O'Reilly to a special performance. Come see our play. There is too much at stake to ignore its message.

Shares