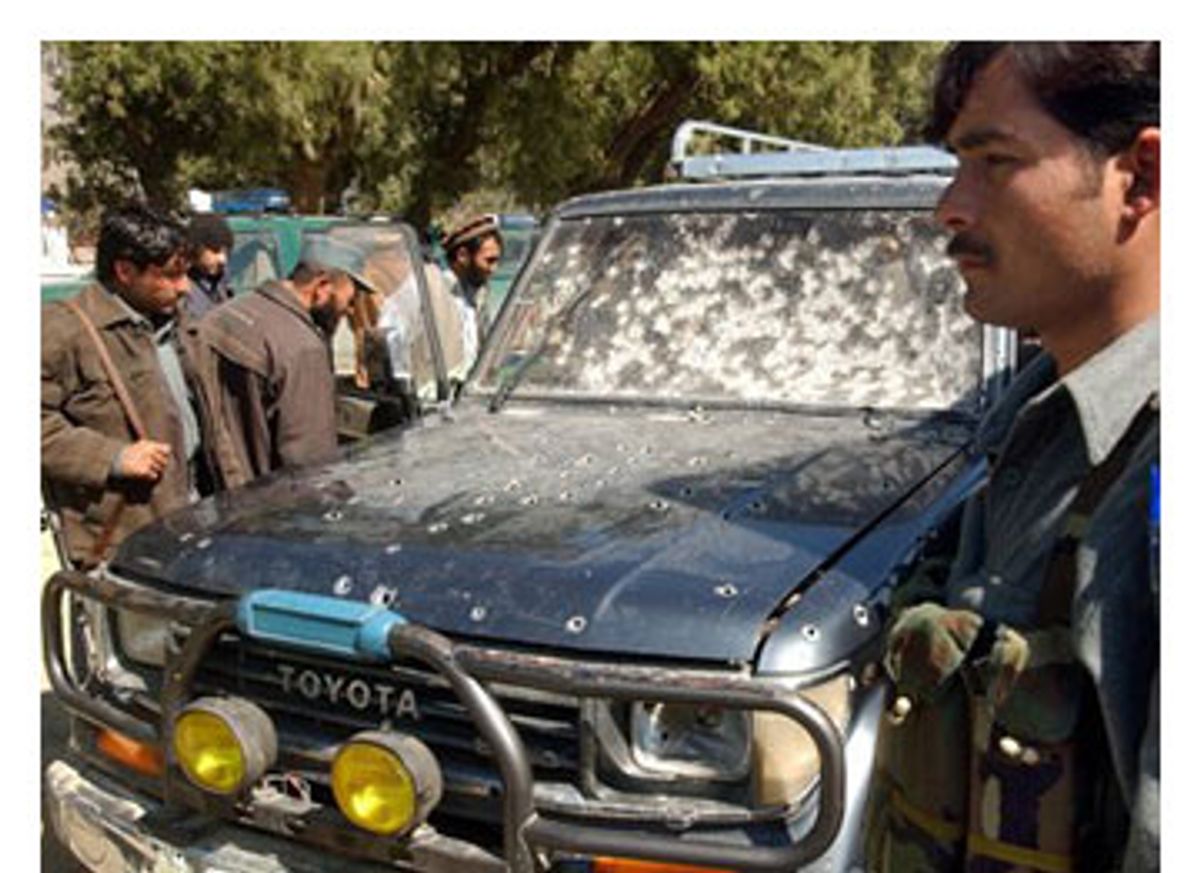

On March 4, a U.S. Marine convoy in the Nangarhar province of eastern Afghanistan was attacked by a suicide bomber driving a minibus, wounding one American. Exactly what happened next remains unclear. According to an investigation by an Afghan human rights group released on April 14, the Marines, who said they came under small-arms fire after the bombing, went on a rampage, shooting at vehicles and pedestrians along 10 miles of road. At least 12 civilians were killed and another 35 were injured, including one infant and three elderly men. A 16-year-old girl, newly married and carrying a bundle of grass to her family's farmhouse, was shot in the back. A 75-year-old man was shot so many times that his son had trouble recognizing him when he reached the scene.

A few hours after the shootings, the Marines returned to the primary site of the carnage, cordoned it off, and allegedly began removing evidence that it had occurred. Seven journalists representing multiple media outlets complained that the Marines confiscated their equipment and forcibly deleted photographs taken by Afghans working for the Associated Press. According to a protest letter later filed by the AP bureau chief for Pakistan and Afghanistan, one Marine raised his fist at the photographers, warning them that he did not want to see any photos of the scene published anywhere. One journalist said he was told, "Delete the photos or we'll delete you."

After conducting an initial inquiry into the matter, the American military command in Afghanistan found no evidence that the Marines had come under small-arms fire after the bombing and took the highly unusual step of expelling them from the country. "The unit responded to the ambush," according to a military spokesman, "and the local population perceptions of that response have damaged the relationship between the local population and the Marine special operations company."

We have seen a story like this unfold before in Haditha, Iraq, where Marines stand accused of killing 24 Iraqi civilians in 2005 after an improvised explosive device killed one Marine. While there is no direct connection between Haditha and Nangarhar, the incidents are troublingly similar: an insurgent attack followed by a gross overreaction by American forces (specifically Marine units), a bumbling coverup, and an eventual investigation by American military authorities -- one that seldom if ever holds anyone genuinely accountable above the level of foot soldier.

As with so many issues in war, the closer you look into a situation, the harder it can be to judge. As a former Marine officer, my first impulse is, somewhat predictably, to sympathize with the troops. Judgments come easy when you're sitting in the comfort of your living room, but when you are taking fire from seemingly every direction, the finely wrought laws of war start to seem like the dreams of a war college professor. I've interviewed hundreds of soldiers and Marines who have served in Iraq and Afghanistan and I'm repeatedly struck by the weighty, almost metaphysical, overtones of modern combat, in which soldiers have a half second to make the right decision and many years to live with the results of making the wrong one. (And those are only the scenarios, of course, in which the soldiers live to tell the tale.)

But one of the great tragedies of incidents like Haditha and Nangarhar is that no matter how they are adjudicated by the Pentagon, they are resounding defeats in a global conflict whose battlefield is ever media-oriented. They draw dark comparisons in the U.S. media with the My Lai massacre in Vietnam, provide fodder for anti-U.S. sympathizers elsewhere, and fit conveniently into the larger meta-narrative of quagmire and American perfidy overseas.

As Abu Ghraib demonstrated so starkly, American military atrocities are more than localized moral failures: They are events with deep and troubling strategic implications. They help perpetuate the image of the American war on terror as a genocidal crusade against Muslims, providing insurgent Web site operators with ammunition in the ongoing propaganda war against the United States and its allies. They undermine the international credibility of the U.S. military, making it that much harder to attract allies to work alongside American forces. And they destroy any hard-won trust of U.S. troops among civilian populations: More than the actual, complicated facts behind the killing of civilians, it is frequently the perception of the locals that matters most.

The similarity between the events in Nangarhar and Haditha underscores the fact that the war in Afghanistan has grown increasingly Iraq-like in terms of the overall fight between insurgents and American forces. Since 2005, Taliban attacks have grown more savage and suicidal, and they have targeted the civilian populace. The United States has responded by ratcheting up offensive operations, including those in the provinces bordering Pakistan where Osama bin Laden is rumored to be holed up. Every year since 2002 has been deadlier than the last in terms of conflict-related casualties. President Bush just pledged another $10 billion to stabilize and rebuild Afghanistan. But the Taliban has vowed a spring offensive, and as one recent Salon report showed, there is not enough military manpower to stabilize the country.

Some U.S. troops, including the Marine unit in question, may not be adequately prepared for the challenges of a counterinsurgency in Afghanistan, which depends on winning the trust and loyalty of the local populace. Part of the problem no doubt is the scarifying institutional experience of the Marine Corps, the military branch that prides itself on its singular ferocity in battle, and which of late has been almost exclusively focused on conducting high-intensity combat operations in the restive Anbar province of Iraq. (Over the course of the Iraq war, casualty rates in Marine units have run roughly twice that of comparable U.S. Army units.) In this respect, I found the general mindset telling when I embedded with Marines who were training Iraqi security forces in Anbar in 2006. "The reason I joined the Marine Corps was to get into gunfights," one Marine stationed near Fallujah told me. "I hate all this nation-building bullshit."

In my view, it was no coincidence that many of the Marines implicated in the Haditha atrocity had fought in the battle of Fallujah in November 2004. As another Marine, stationed near Ramadi in 2006, said to me scornfully, "The last time we were here, we were shooting everyone in every building we entered. And now they want us to pass out candy and soccer balls?"

While it is not known how many of the Marines implicated in the Nangarhar incident had served in Iraq, the unit was an elite special operations platoon that accepted only highly experienced Marines, so it's likely that many if not most of its members had done multiple tours in Iraq. This seems to point to a potential problem as the wars in both places drag on: Can a veteran of intense combat forget everything he has learned and participate in operations requiring "softer" tactics and a lower threshold of violence?

The Army, by contrast, has been dealing with a larger spectrum of operational environments and has had the luxury of developing what is, in many cases, a more nuanced counterinsurgency approach than the Marine Corps. The softer Army approach is best exemplified by the rise in Baghdad of the so-called Petraeus boys (in reference to the current U.S. general in Iraq, David Petraeus), including military commanders David Kilkullen, H.R. McMaster and John Nagl, who speak of counterinsurgency as "a thinking man's game" and focus on efforts to secure the safety and support of the local population. In 2006, I saw the disparity and resentment between the Army and Marines on display in Ramadi, a town overseen by an Army command, but under which many Marine units serve. One particularly outspoken Army captain declared his open distrust of Marines, calling them "the butchers of Haditha."

The Army-dominated Special Operations Command is known for its secrecy and lack of media transparency, so the publicity around the Marine unit's removal after Nangarhar was striking. Some observers have speculated that the unit was expelled from Afghanistan and its departure announced to the international media as a kind of gesture of goodwill to the people of Nangarhar -- an attempt to repair the political damage done. The move might also have been an attempt to forestall revenge attacks against the Marine unit.

Obviously, the innocent victims of these sorts of atrocities deserve our best sympathies, but whenever I speak with Americans about Iraq and Afghanistan, and everything we're doing wrong there, I also feel compelled to remind them that our troops are among the most disciplined and restrained that the world has ever seen. The American occupations in those countries are regularly compared to the French counterinsurgent campaign in Algeria from 1954 to 1962. It is worth remembering that France -- a country that never went through a period of self-examination as the United States did after Vietnam -- operated concentration camps for the most of the conflict, torturing and summarily executing hundreds of Algerian citizens that it found undesirable. American troops have committed some exceedingly bad errors of judgment in both Iraq and Afghanistan, but none of them approach what can be considered the historical norm for counterinsurgent wars.

It is also worth remembering that nearly 700 civilians were killed by the Taliban last year. According to the New York-based Human Rights Watch, the civilian death toll caused by militant Islamist groups is more than three times the total caused by U.S. and NATO forces in Afghanistan. According to Joanne Mariner, the group's director on terrorism and counterterrorism, "The insurgents are increasingly committing war crimes, often by directly targeting civilians."

But an incident like Nangarhar causes outsized collateral damage, allowing for emphasis on the theme of American military power misapplied. On the whole, our sins in Iraq and Afghanistan have mostly been sins of ignorance and negligence rather than malice. The difference is that today's media-saturated world makes it nearly impossible to hide incidents in which the troops screw up badly.

Among many troops I have spoken to about U.S. atrocities, there is a sense of rank unfairness about the military justice system. With few notable exceptions, it is always lower-ranking enlisted men and most often infantrymen who stand accused. Pilots, artillerymen and officers above the rank of captain are almost never charged with war crimes -- never mind civilian leaders at the Pentagon, elected officials or members of the foreign policy establishment who advocated the wars in the first place. "Shit runs downhill," the saying goes, and as a rule in the military, it's true. To be sure, the commander and senior enlisted man of the Marine unit at Nangarhar were relieved of their command positions, but, as of yet, no charges have been filed against them. This repeats the same general pattern of prosecution at Haditha and at Abu Ghraib.

Our troops in the field have to be held to a standard of conduct, even if the enemy is not, and even if the military justice system has historically been stacked against them. Just because they might feel under siege does not relieve them of the responsibility to act morally and follow the rules of engagement. Nor are their leaders relieved of command responsibility if their troops in the field fail to do so. Failure at either level is not only immoral but counterproductive, and with enough repetition, could ultimately help lose the wars.

Shares