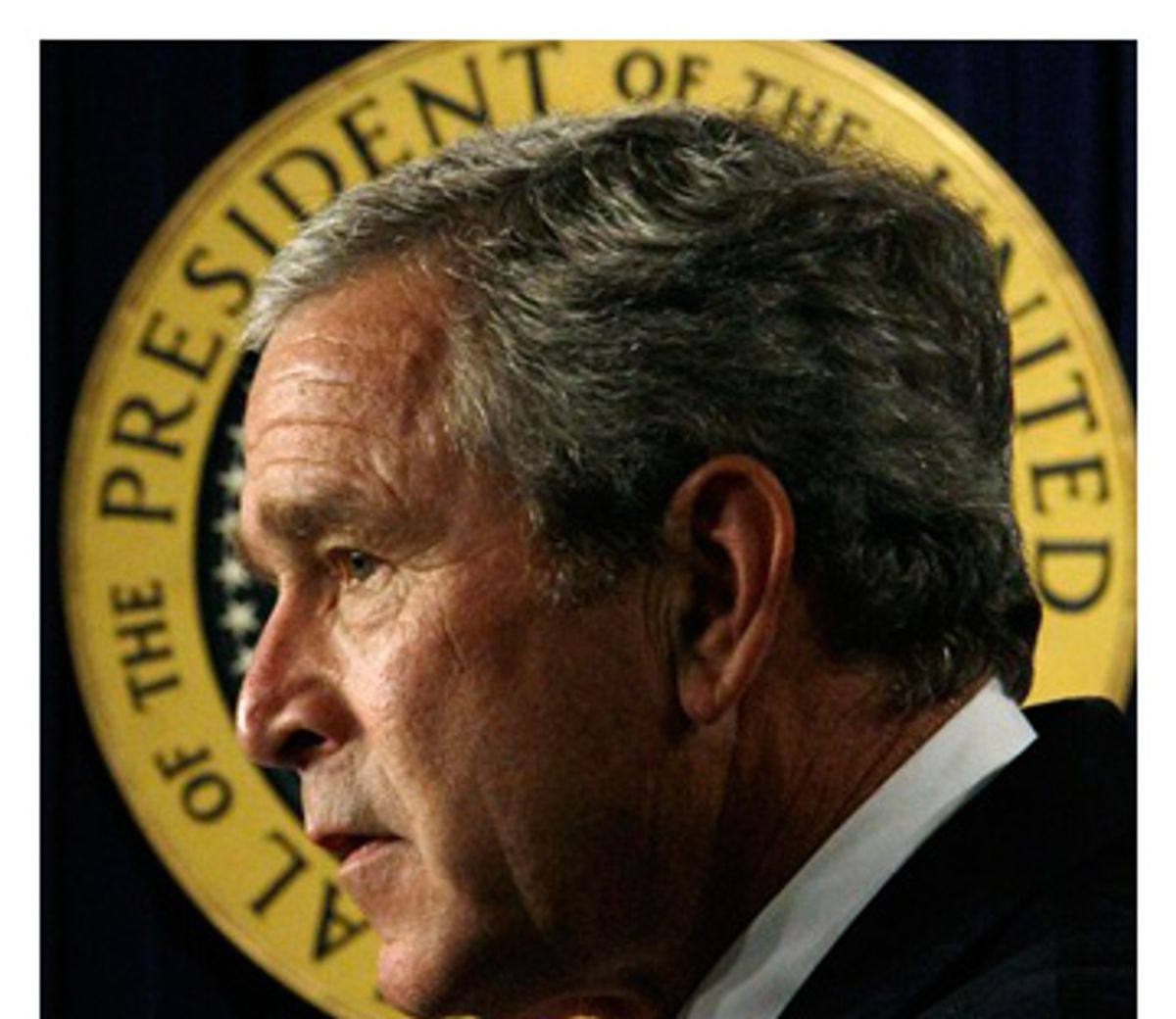

The Bush administration, already arguably the most aggressive advocate of unchecked executive power in the history of the American presidency, has done it again. President Bush has defied a congressional subpoena for testimony and documents related to his politically and legally suspect firing of a group of U.S. attorneys. Invoking "executive privilege," Bush directed two former White House employees -- Sara Taylor, who was his political director, and Harriet Miers, who was his White House counsel -- not to testify about any "White House consideration, deliberations or communications" on the matter. Taylor said little of substance before lawmakers on Wednesday, while Miers retreated from testifying at all. Bush has refused not only to turn over any documents, but even to delineate which documents he claims the privilege protects. Congress claims constitutional authority to demand the documents; the president claims a constitutional privilege to refuse that demand.

If history is any guide, the resolution to this constitutional clash is likely to be political, not legal. Ordinarily, that would be good news for the president, because when claims of executive privilege and immunity have reached the Supreme Court, the results have not always been to the president's liking. In 1974, the Supreme Court ruled that President Nixon had to turn over tapes related to the Watergate burglaries, and Nixon resigned in disgrace shortly thereafter. In 1997, the court rejected President Clinton's claim of executive immunity from a sexual harassment suit by Paula Jones -- and we all remember where that led. Given that record, the Bush administration might prefer the political forum.

But it has precious little political capital, and not only because Bush is a lame duck, and responsible for an unnecessary, unpopular and disastrous war. This administration has played so fast and loose with claims of confidentiality and privilege over the last six years that it has lost all credibility. And in the political arena -- particularly where the public by definition cannot know what the White House is trying to hide -- credibility is everything.

Start with the headlines. Would you believe an administration that so confidently told us that Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction? Or a president who proclaimed the "mission accomplished" in Iraq in May 2003? Or who broke from his own tradition of denying all requests for commutations or pardons except where there was evidence of actual innocence to commute the sentence of the vice president's chief of staff, who was convicted of lying to cover up the apparent wrongdoing of his boss?

But the credibility gap is even deeper on the specific issue of confidentiality. Most recently, Vice President Cheney made the remarkable assertion that he is not a part of the executive branch when it comes to complying with rules and regulations regarding the maintenance of executive office records -- despite successfully invoking his executive status previously when seeking to keep secret the identities of industry officials with whom he met to discuss energy policy. The only thing consistent about his claims was a desire to use confidentiality to trump accountability.

The Bush administration has routinely invoked secrecy to bar efforts to hold it accountable for its failed initiatives in the war on terror. In the first several weeks after 9/11, it rounded up hundreds of foreign nationals in secret and held them in preventive detention. To this day, the detainees' names remain secret, even though the FBI eventually cleared them all of any connection to terrorism. Hundreds were tried in secret immigration proceedings, closed to the public, the press, human rights observers and even members of Congress, even though, again, none were accused, let alone found guilty of any charge of terrorism.

The administration has also shrouded its controversial interrogation practices in secrecy. It has refused to disclose what tactics it authorized the CIA to employ in secret prisons, or "black sites," despite widespread reports that these tactics have included simulated drowning and other brutal treatment. It has recently issued transcripts of hearings at Guantánamo involving black site detainees, but has redacted all complaints by the detainees regarding how they were treated. And it has refused to let attorneys for those former detainees even meet with their clients, arguing that the detainees might tell the attorneys what happened to them while in the black sites and could reveal classified information. In short, the administration has invoked secrecy to obscure its involvement in torture.

Meanwhile, the administration has fought off lawsuits challenging other policies -- its secret handing over of terrorist suspects to foreign interrogators (known as "extraordinary rendition") and warrantless wiretapping of Americans' telecommunications -- by invoking a "state secrets" privilege, whereby it claims that even if the administration acted unconstitutionally and illegally, there is nothing the courts can do about it because its legal violations were themselves a secret. From this point of view, secrecy overrides all other constitutional values, including the right of a human being not to be sent to another country to be tortured.

All the while, the administration has selectively disclosed secret information when it has served its political purpose. The outing of CIA agent Valerie Plame in retaliation for her husband's temerity in challenging the asserted evidentiary basis for the war against Iraq is only the most infamous example. John Ashcroft, when he was attorney general, was particularly fond of this tactic. In the midst of the Patriot Act debates, he selectively declassified the fact that one Patriot Act provision objected to by librarians had never been used against a library. Not until years later did we learn that another Patriot Act provision, relating to national security letters, had been widely abused, including against a consortium of libraries. And when Ashcroft testified before the 9/11 Commission, he selectively declassified a memo for the sole purpose of insinuating -- falsely -- that the Clinton administration was at fault for the barriers between law enforcement and intelligence officers, which were cited as part of the failure to stop the terrorist attacks. (In fact, those barriers long predated the Clinton administration, and had been endorsed by Ashcroft's own deputy, Larry Thompson, before 9/11.)

Last fall I attended a talk in London by a former counterterrorism official in Tony Blair's government. He noted that in the struggle against terrorism, it is often necessary for the government to take measures that are ultimately justified by evidence that it cannot share with the public. At the same time, if those measures are to be successful, they need the public's full support. As the official put it, this dilemma puts a premium on trust. It is especially important that the government act above reproach in times of crisis, he said, in order to maintain the public's confidence.

The Bush administration has lost the confidence of the American public, nowhere more so than on claims of unchecked executive power and privilege. Its chief proponent of executive supremacy, Vice President Cheney, now has an approval rating of 13 percent, the lowest of any vice president in the nation's history.

With these circumstances, the Bush administration may ultimately prefer a resolution through the courts. At least it has a majority there.

Shares