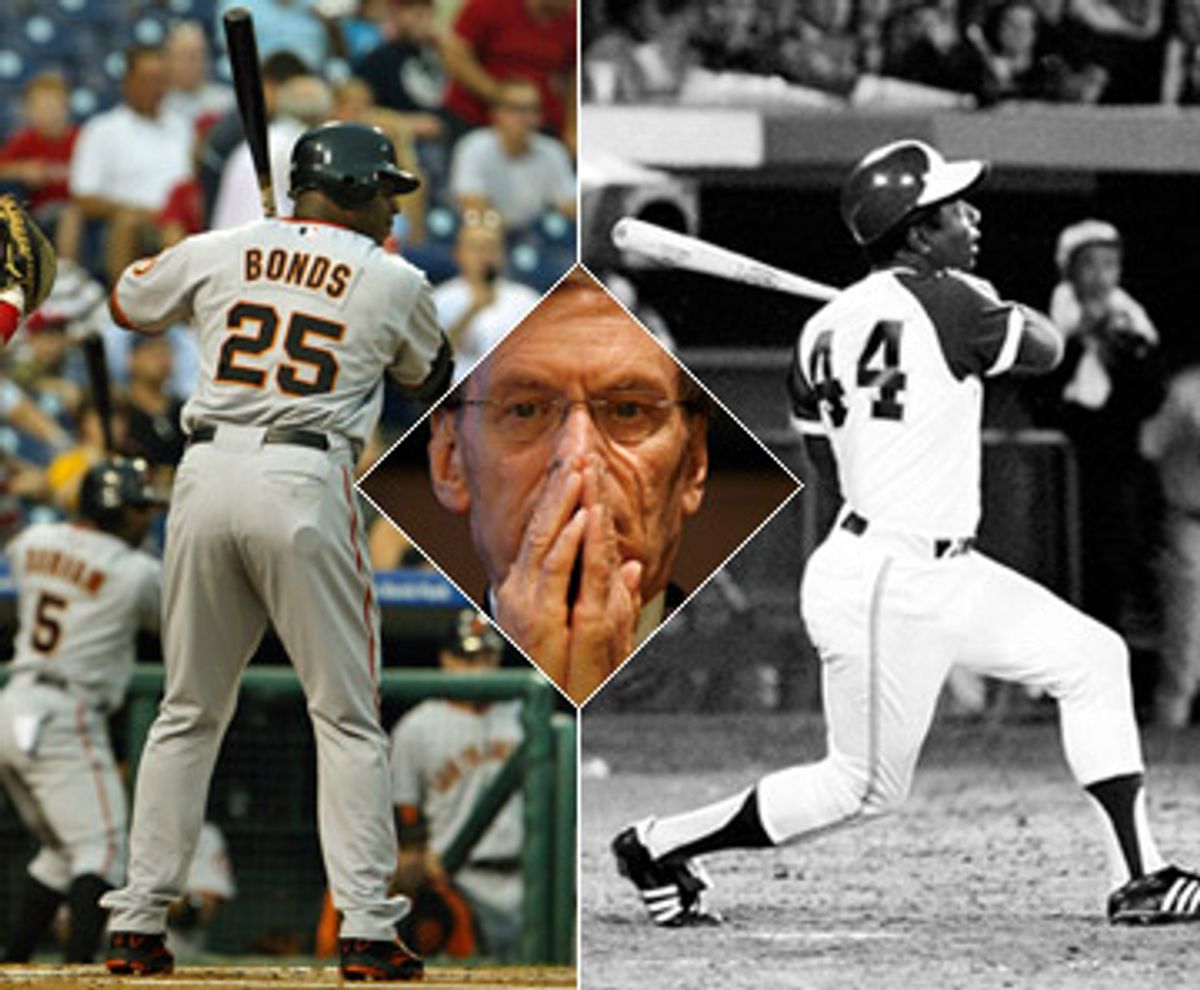

On April 8, 1974, when Hank Aaron broke Babe Ruth's all-time career home run record with his 715th homer, one important person was not in Atlanta's Fulton County Stadium: baseball commissioner Bowie Kuhn. Aaron had endured literally tons of hate mail and numerous death threats in gracefully ascending to the record of a white American icon. The commissioner had declined to witness the shattering of the greatest record in sports, in which a black American hero risked his life every time he came to bat, in favor of honoring a previous commitment to address the Wahoo Club, the Indians' fan club in Cleveland.

Thirty-three years later, another commissioner faces a choice: to be a witness to history, when Barry Bonds breaks Aaron's record, or to stay away. Although Bonds' journey to the home run record can scarcely be compared with Aaron's, baseball commissioner Bud Selig should not make the same mistake as his predecessor. Selig should be in the house when Bonds clubs home run No. 756. Maybe Bonds will make it easy on you, commissioner: If he hits three homers this weekend, you can watch the record fall at home in Milwaukee.

Selig seems torn between his decades-long friendship with Aaron -- who has said he will not attend -- and his duties as a commissioner in 2007. Selig knows what Aaron endured, especially in 1972 and 1973, when he received 929,000 letters, mostly opposing his assault on Ruth's record, and many in the ugliest terms. "You can hit dem home runs over dem short fences," declared one of the milder screeds, "but you caint take that black off yo face. Rite on, rite on." Other letters threatened death if Aaron didn't retire. "Will I sneak a rifle into the upper deck or a .45 into the bleachers?" one anonymous writer mused. "I don't know yet." Aaron had a 24-hour bodyguard, slept in a separate hotel from his team, and his daughter, a victim of kidnapping threats, attended college under FBI protection. Aaron's quiet dignity in approaching 715 therefore became an extension of the civil rights movement, embraced at the time by Jesse Jackson, Andrew Young and other black leaders.

"That was a time when Martin Luther King was saying, if you haven't found something you're willing to die for, you probably aren't fit to live," Young told me in 1999, as I researched a book on Aaron. "I think Hank had decided that his life was vulnerable, and if it meant dying in the course of doing his best, I don't think he actually worried about it."

Against that legacy, Barry Bonds has virtually no claim. But then, neither does any ballplayer in the last three decades. If Aaron played in the era where African-Americans taught the whole country about grace and excellence in the face of adversity, Bonds plays in the equal opportunity era of cheating and steroids. But it is hardly fair to lay all the blame on Bonds, and that is why Bud Selig should come to the ballpark, unlike Kuhn and his bungling no-show in 1974. Indeed, a case can be made that Barry Bonds is being unfairly singled out.

Despite the apparent evidence of Bonds' cheating, the commissioner should consider: How many other players have taken steroids? Why did Major League Baseball, and the commissioner himself, do little during the decade of unscrutinized Paul Bunyan-size players and their towering homers? How many great pitchers who today throw hard past the age of 40 can themselves be beyond suspicion? And, if Bonds' accomplishments are in question, shouldn't we look at our attitude toward all potential records? If Selig won't go see Bonds break Aaron's record, then he shouldn't attend any games where the whiff of steroids is in the air.

Beyond steroids, there's something else that feeds the perceptions of Bonds. The slugger is portrayed as brooding and angry. "Anger from black men is one of the things white America fears," Dr. Alvin Poussaint, the Harvard psychiatrist, told me. He was talking about the 1998 race between Sammy Sosa and Mark McGwire for Roger Maris' single-season homer record, when Sosa was portrayed as the "best man" who "understood that if he was in any way threatening or boasting about how he was going to 'get' this guy, he would have been rejected by the American public." Sosa, smiling and blowing kisses, "played the American psyche so well."

Bonds, by contrast, doesn't play Sosa's game, and doesn't seem to care. So the guy's a jerk; who cares? Roger Clemens isn't cuddly, and if you want mean, how about Enos Slaughter going after Jackie Robinson? Ty Cobb, anyone? Bonds, like the others, deserves to be in the Hall of Fame. But his image as sullen and unfriendly helps generate a negative public attitude toward him; for those same traits, many white players would get a pass. It's uncomfortable, but it's true: Race issues may be more subtle now than they were in Aaron's day, but they have hardly disappeared, and they're playing now in the attitudes toward Bonds. In an ABC/ESPN survey, nearly twice as many blacks thought Bonds was being unfairly treated, compared to whites. A commissioner's refusal to witness home run history will only fuel that perception.

As Selig mulls his decision, I well imagine what he's thinking. On his mind is Henry Aaron, and a deeper record from a purer hero. "He was phenomenal," the commissioner told me. "He was magnificent. He was quiet. He was dignified. I never saw anything like it." I couldn't agree more, Mr. Commissioner. Like me, you long for a cleaner time, when heroes stood for something bigger. Bonds doesn't fit that picture. But he remains one of the greatest to ever put on a uniform. And like it or not, he is the product of our culture and our sport in the early 21st century.

Years ago Selig told me something else -- something he would do well to keep in mind: "Baseball is a mirror of society." So it is. We can't blame Barry Bonds for all that's changed in the last 33 years.

So go to the ballpark, Mr. Commissioner. Watch Hank's record fall. Witness the history, even though it won't be the same.

Shares