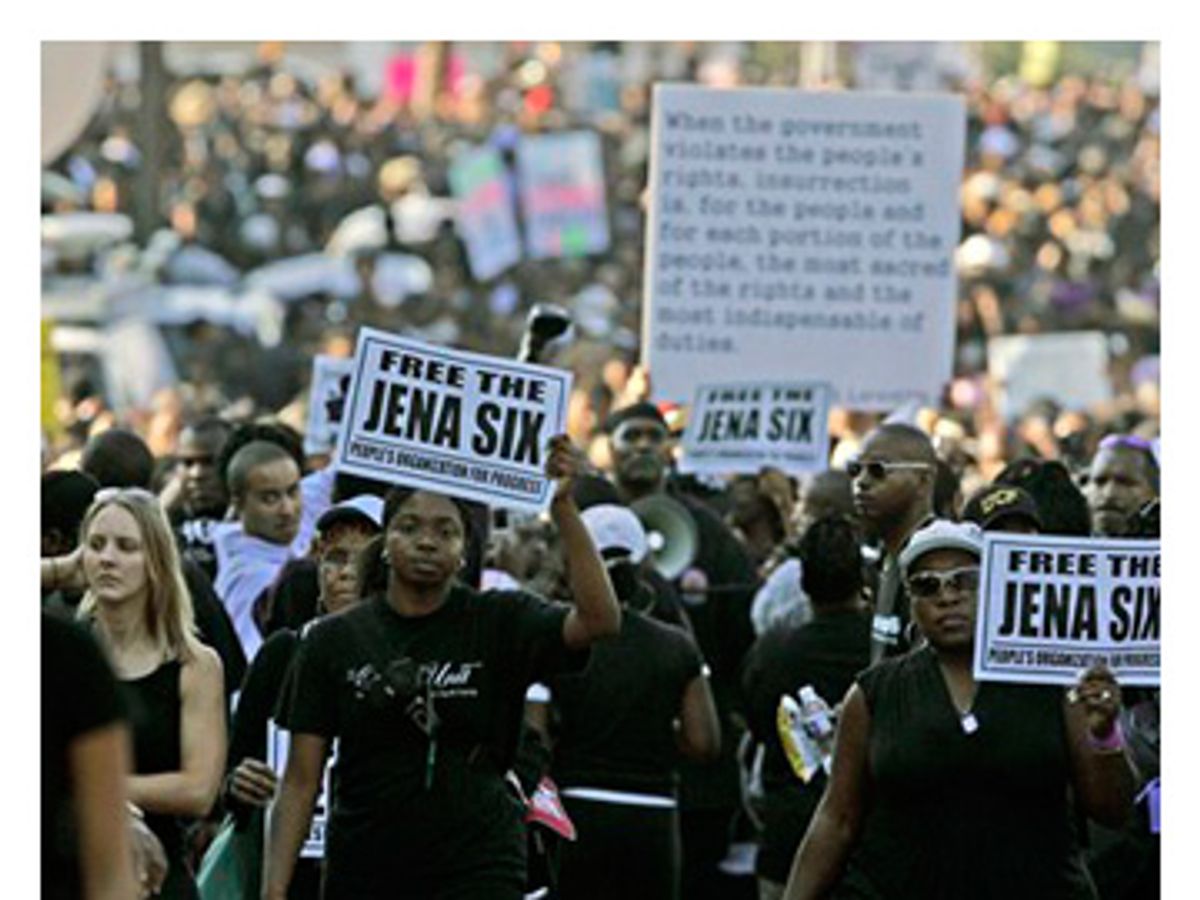

Last week, my brother Ahromuz went to Jena, La., and came back a changed man. He took a bus that left Los Angeles and didn't stop until it had reached the tiny Louisiana backwoods town. The march and rally in Jena last Thursday were the culmination of a year of protests over the felony charges against six black Jena teenagers who had allegedly beat a white student at a high school beset with racial tension. One of the many things Ahromuz found unexpectedly transforming was the presence of so many very different black people -- doctors, lawyers, rappers, black nationalist types -- who had gathered from many points around the country for a single purpose. "It was understood that we were all there for the same reason," he said. "Jena -- it was all that people talked about. There was no disagreement. It was incredible."

Me, I'm ambivalent. Not about the cause of the Jena Six. I support it. Even without the back story, a saga that began in September 2006 with white students hanging nooses from a favored tree on campus as a warning to blacks who dared to gather there, the attempted-murder charges (later reduced to battery) against the black students, and the conviction of one juvenile defendant who had been tried as an adult were, to put it mildly, over the top. I applauded the swift and effective response to the situation, the groundswell of alarm and anger among black people that led to the march on Sept. 20, the day the convicted juvenile, Mychal Bell, had been scheduled to be sentenced; thanks in part to public pressure, the conviction was partially vacated by the trial judge at the 11th hour. The pressure continues with Jesse Jackson and others now calling for a federal investigation into the possible civil rights violations of the Jena Six.

All well and good. And yet the response I found so encouraging and that my brother found nearly magical I also find disheartening, because what has happened around Jena happens much too rarely. Black people burned up the Internet for a year spreading their indignation about the Jena Six. That's appropriate. But where is that indignation for all the other injustices that are killing black people daily, like crappy schools, underemployment, predatory lending, unequal sentencing in drug convictions?

Of course the Jena Six campaign hooked neatly into broader complaints against the racial inequalities of the whole criminal justice system, which is a biggie -- it imprisons young black males at an astronomically disproportionate rate -- and Jena provided a good moment to express that. But agitation and organization shouldn't wait for a moment. That would be like waiting for the entire Ross Ice Shelf to melt into the sea to sound the alarm about global warming. It's a good photo op, but it probably comes too late.

This is not just a black thing. We've all been conditioned to agitate selectively, especially in matters of race. Americans of all colors have come to think of news as only moments -- a plane crash, an election, a lofty acceptance speech. With race, the "moment" is almost always violent or criminal, like the beating of the white student in Jena. Yet here's the irony: The worst things happening to black people are not only not moments but are things not happening at all -- not getting a good enough education, not getting enough jobs, not getting equal treatment. It's a public relations quandary that nobody's been able to fix since the '60s, when we had plenty of visuals -- that is, moments -- to illustrate complicated historical grievances that were finally making it to television. Demonstrations, riots, flag burnings, resistance to arrests, concerts, ceremonial signings of landmark legislation -- these all fed a narrative that the public understood, whether they agreed with the particulars or not.

There is no such narrative now. In this age of deconstruction, what's missing in the Jena case is a cumulative understanding and connecting of dots on racial issues, something that would prevent every American from asking stupid questions like, Are nooses hanging from trees really that bad? (Another version of the wearisome question: Is "nigger" really such a negative word?) We've detached racially charged incidents from a racial context, which sounds liberating but actually skews the racial balance of power even further: Without context, blacks always seem reactive and overreaching, while whites seem calm and fairly neutral. So in Jena, the black citizens say the Jena Six experience confirms pretty much every aspect of the racism they've experienced; whites admit to some lingering problems but insist that things have changed in Jena for the better. The facts are not in dispute as much as what the story of the Jena Six means -- a manifestation of institutional racism that's never gone away? An isolated case of prosecutorial excess in an otherwise idyllic town? The media tends to settle into a noncommittal, "fair and balanced" discussion that avoids conclusions and judgment of any kind, at least on the surface. And that's where we leave things until the next moment hits. If we're lucky.

There's also the problem of familiarity breeding contempt, or a certain numbness, with any stories coming out of the Deep South. All the elements of legal oppression instituted after Reconstruction are in the Jena Six case: forbidden territory, nooses, outrageous accusations, an all-white jury convicting a black defendant in record time, indifferent representation of the black defendant by counsel, who called no witnesses (though the modern twist is that the counsel in this case was black, too). As Americans we are all initially stunned and say, what, this is happening again? Impossible. Can't be. The split happens in the next reaction: Blacks are concerned, whites are ... annoyed. Blacks see an ugly continuum; whites see a dotted line at most.

There is also a generational split among whites. High school students living in a post-integration era (for those few schools that actually integrated to some degree) often view black-white interaction differently from how their parents and grandparents view it. Friction is racial, but it's not always their fault. Blacks can make trouble and spoil for fights as well as anyone else, and whites have a right to fight back. That's not untrue, though minus the context -- the isolation and separatism of a place like Jena built up over years of culture and practice -- it only resonates so far.

At least Jena has some black-white interaction to consider; in much, much bigger cities like L.A., where diversity is supposedly a point of pride, the great majority of public schools have no whites to speak of at all. It's a different narrative altogether.

The bottom line is that, racism notwithstanding, blacks have to create and sustain their own narrative and make their own moments if they are to break out of a rut so vividly illuminated by the case of the Jena Six. My brother Ahromuz believes it's entirely possible that will happen -- a belief forged by the sense of unity he experienced, of all places, in Jena. He said that among the doctors and lawyers were hordes of young people. College-age people. People not far out of high school. "They really wanted a change of some kind," he said. "They want to go further. They felt, there's got to be something else we should be doing. If this is what black people can do on a reactionary tip, imagine what we can do on an actionary tip." He breathed in deep. "If we don't do something now, it'll be a big waste. Actually, I can't wait to get past Jena." That makes two of us. It's a start.

Shares