It's a piece of Michigan lore that belongs right up there with Pere Marquette dying in the wilderness, or Berry Gordy discovering the Supremes.

Summer of 1972. Flint. A young man was manning a gas pump when a General Motors executive drove up.

"Why aren't you working in the shop?" asked the driver, whose company was desperate for strong arms to build GM's armada of Buick Electras and Cadillac Fleetwoods.

The pump jockey shrugged, so the recruiter took down his number. A week later, the kid was dragooned into service as an autoworker, the most enviable blue-collar occupation in the world. He had "more health insurance than Evel Knievel could piss away in a million bus jumps," as Flintoid Ben Hamper put it in his darkly hilarious shoprat memoir, "Rivethead." And in 30 years, he could retire on full benefits, with enough money to open a motorcycle detailing shop or buy a fishing lodge Up North. That's why the company was nicknamed "Generous Motors."

This week's United Auto Workers strike seemed like an act of nostalgia for those days. It was the first walkout against GM since 1970, and its central demand -- more job security -- asked the company to restore a promise it hasn't been able to keep for over a generation. It was merely the latest in a long, relentless and accelerating series of signs that my home state, at least as I knew it, is circling the drain.

When I was growing up in Lansing, Mich., in the 1970s, General Motors was the largest private employer in the world. Lansing was the birthplace of the Oldsmobile, and the model's logo glowed in pink neon script above the Grand River plant. (The river below also glittered in unnatural colors.) The United Auto Workers numbered 1.5 million -- three times its current strength -- and the whole city knew when Local 652 was electing a new president, because the candidates bought airtime on the radio.

My high school, J.W. Sexton, was across the street from GM's Fisher Body assembly plant. The air we breathed was suffused with the chemical tang of atomized paint. And facing every gate was a tavern or a party store, for post-shift beer runs. The school and the shop seemed like part of a unified industrial complex. Sexton produced students, who grew up to produce cars.

By the time I started high school, that link in the process had been severed. It was 1982, the rock-bottom pits of the Rust Belt recession. Auto work was not my class's calling. Our chemistry teacher, Mr. Deslich, began each semester with this warning: "They used to say there was a tunnel from the graduation stage to Fisher Body. That's not there anymore. You can't count on a job in the plant. You're going to have to study and go to college."

It was wise advice. At its peak, in the late 1970s, "The General" enlisted 600,000 hourly workers. Today, it's down to 73,000. So where do you work if you blew off high-school chem? Well, Wal-Mart is now the world's largest employer.

The Oldsmobile nameplate has been stripped from GM's roster. You have to go to Lansing's R.E. Olds Museum to see one. Fisher Body is being torn down, by a company with the Big Brother-ish slogan "Demolition Means Progress." Sexton's student body is half what is was when I graduated, and in the surrounding neighborhood, you can see an abandoned elementary school, and aluminum bungalows tagged with repo stickers.

My best friend from high school still lives in Lansing. He repairs lottery machines. It's one of the more secure jobs in town.

"When people are out of work," he says, "we get more business."

The UAW strike was just one distressing headline in a week of bad economic news for Michigan. As usual, the state has the nation's highest unemployment rate -- 7.2 percent. (In 2005, it was the only state not hit by a hurricane to lose jobs. It regularly wins United Van Lines' title of most-fled state, and the state of Wyoming put up a billboard outside Flint to lure workers west. That's a reversal of Henry Ford's old practice of sending his agents to wander the South handing out free one-way train tickets to Detroit.) On Friday, thousands of state employees will be told whether to report to work next week. Thanks to obstinate Republicans in the state Legislature and an ineffectual Democratic governor, Michigan may not meet its Oct. 1 budget deadline. The governor wants to raise taxes. Republican legislators want to freeze school funding and cut social services. If they can't agree soon, the state government will shut down. Drivers have been warned to renew their license plates now. The state police won't patrol the roads, and even the casinos will close.

How did the state that Franklin D. Roosevelt called "the Arsenal of Democracy" fall on such hard times? By clinging too hard to that title, is how. Michigan is hopelessly attached to the 20th century. It's not just the UAW with its longing for graduation-to-grandparent job promises. The Big Three have never gotten over the idea of muscular American cars ruling the highways. The SUV -- pumped-up descendant of the Fleetwood and the Electra -- was the automotive status symbol of the 1990s, so profitable that Detroit turned up its nose when Japanese automakers introduced hybrid cars.

"Hybrids are an interesting curiosity," then-GM chairman Robert Lutz said in 2004. "But do they make sense at $1.50 a gallon? No, they do not."

This year, with gas at $3 a gallon, GM is introducing a flex-fuel vehicle called the Volt, which can run on electricity, biodiesel, E85 or gasoline. But by waiting so long, GM yielded the title of environmentally friendly automaker to Toyota. The Prius will always be the hybrid car.

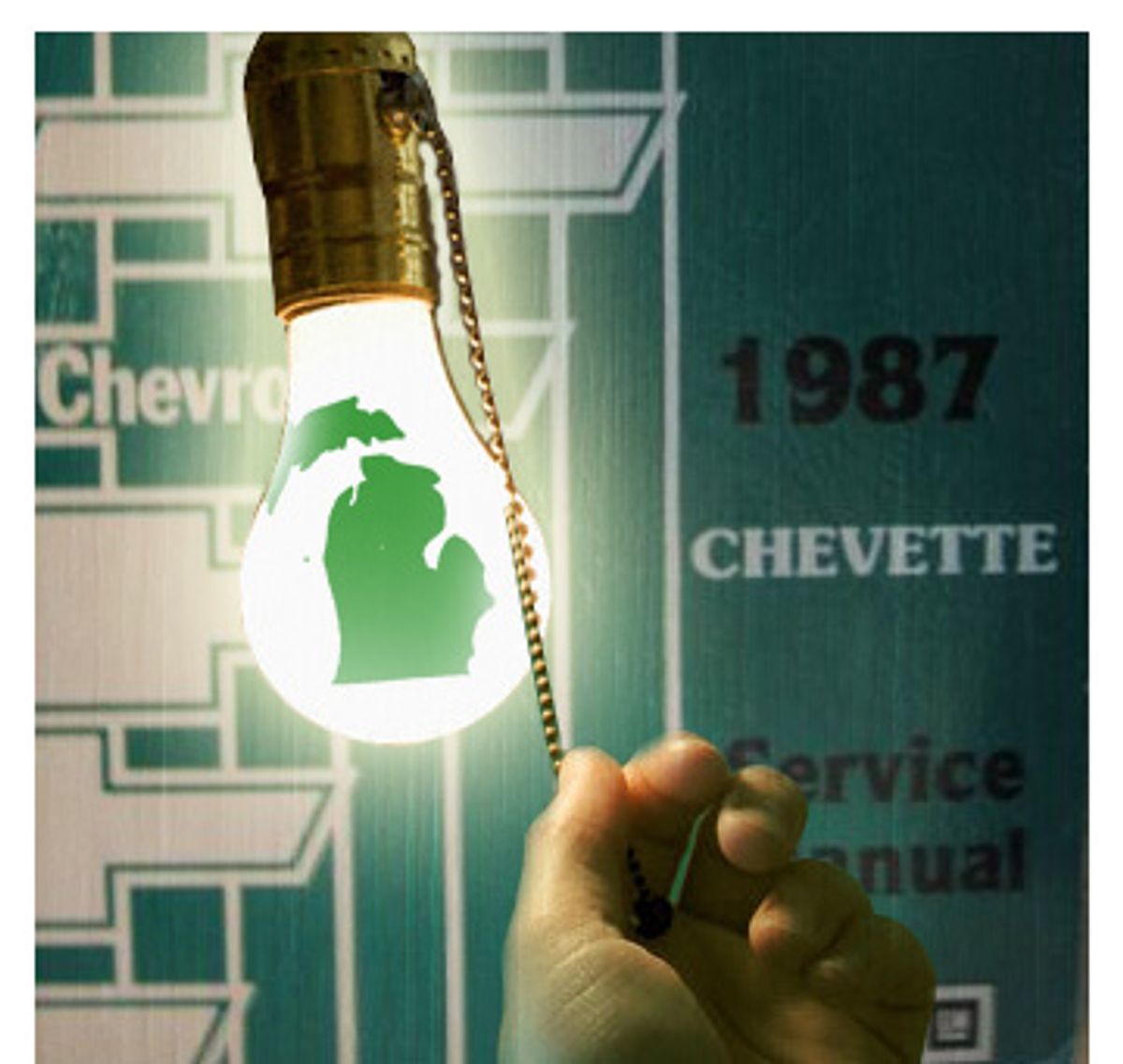

Detroit made the same mistake in the 1970s. It was too late getting into the small-car market, and the efforts it turned out were junk. My factory-town DNA tells me that buying American is a patriotic duty (as did the graffito "Assholes Buy Jap Cars" that I once saw painted on an overpass near Flint), so I suffered through the Chevy Chevette, the Ford Escort and the Plymouth Volare. I think I abandoned them all on rural roads, with blown head gaskets. My Ford Focus runs like a dream, but it can't seem to compete with the Corolla. This year, Toyota will become the biggest-selling automaker in the world.

When I think of Detroit's stubborn self-image as "the Motor City," I think of the Boll Weevil Monument in Enterprise, Ala. Enterprise was a town that grew cotton, and no other crop. After boll weevils struck, the farmers thought their livelihood was over. Then they started planting other crops, such as peanuts, and prospered more than ever.

Michigan did not become great because of the auto industry. The auto industry became great because of a Michigander, Henry Ford. The state still produces creative people. Google founder Larry Page, a Ford of the 21st century, grew up in East Lansing, and studied at the University of Michigan, whose main function seems to be giving young Michiganders the credentials to get the hell out of Michigan. Page went to California, but as a sop to his home state, Google is opening a 1,000-employee office in Ann Arbor.

(I've moved back to Michigan three times since college. My last attempt lasted a year -- until I was laid off. I now live on the North Side of Chicago, which is so crowded with my fellow economic refugees that we call it "Michago.")

I can only hope Google Ann Arbor is the beginning of a post-industrial era for Michigan. The picketers in the UAW's two-day strike were mostly gray-haired, protecting jobs and benefits they've held for years. Like the music of Bob Seger -- who celebrated Michigan's glory days with "Makin' Thunderbirds," "Night Moves" and, fittingly, "Back in '72," -- auto work belongs to the baby boom generation. GM has been culling them as quickly as possible, buying out 35,000 last year.

They're not being replaced with younger workers. My generation never heard the promise. We never counted on a career in the shop. If we have a mission, it's finding Michigan a new industry, and a new image, that take it beyond the automobile.

Shares