This week President Bush will convene an international conference in Annapolis, Md., to promote the "two-state solution" for Israelis and Palestinians. The meetings and noble proclamations toward that goal, however, will bear little relation to reality here in the Middle East. Essentially, Bush is too late. For most Israelis, the two-state solution already exists.

When I grew up near Tel Aviv in the 1970s, Palestinians from the West Bank and Gaza were an indispensable part of the environment. Many of them worked in construction sites, laboring to turn my hometown's strawberry fields into a modern suburb. Others stood every morning in line at the town's highway intersection -- a common sight in Israeli cities then -- waiting for their chance to get a day job. Luckier Palestinians got jobs filling gas at service stations, washing dishes in restaurants and bars, or fixing cars. They served Israeli customers, and were even given Hebrew aliases by their employers. Thus, Ghazi became "Roni" and Mustafa turned into "Moti." Despite a class system problematic in its own right, many of these workers experienced at least a measure of integration.

"The Arabs," as they were called then, manned our country's service sector for two decades after Israel occupied the West Bank and Gaza in June 1967. But lacking civil or political rights, this underclass rebelled in December 1987. Termed the first intifada, the Palestinian uprising abruptly changed Israel's reality. Palestinian workers disappeared from sight, first the young ones, then the elders.

Born a few months after the outbreak of the first intifada, my daughter grew up in a very different environment than I did. She has never met a Palestinian from the West Bank or Gaza. Now 19, she has seen our Palestinian neighbors only on TV, and views them as aliens. She is much more familiar with American brand names and sitcom characters than with the people who live 15 miles east of her Tel Aviv home.

My daughter is far from alone in her experience. Today's mainstream Israelis living comfortably in the Tel Aviv area hardly ever cross the "Green Line" separating Israel from the West Bank. In pre-intifada times, many Israelis traveled the short distance up the hills to buy cheap furniture at Bidyah or get their cars fixed in low-cost workshops in Jenin. Not anymore. Since the much bloodier second intifada erupted in September 2000, all Palestinian towns and villages are legally off-limits to Israelis. Moreover, few Israelis would even visit the controversial Israeli settlements on the hilltops. (Conversely, their religious, highly ideological inhabitants would feel out of place in Tel Aviv, just like Palestinians would.) Now, the only reason to go to Nablus or Ramallah, or to one of the Israeli settlements around them, would be for military duty. Otherwise, entering these towns is a life-threatening prospect for Israelis.

Even the Old City of Jerusalem, officially a sovereign part of Israel, has lost its appeal for most Israelis. As a child and teenager, I toured the Old City's alleys, the souk and holy places countless times with my family, my classmates and my friends. We would walk on top of the Ottoman-built wall, or eat hummus at Abu Shukri and have tea down the alley in the Christian Quarter. Imagine visiting one of the world's most exotic wonders, within an hour's drive from home! But few Israelis who grew up in the post-intifada reality would even recognize these places now. These days, I visit the souk only when I have visitors from abroad. For many of my peers in Tel Aviv, the Old City is more remote than New York, London or Thailand. For them, the Jewish part of the city suffices. They see East Jerusalem, with its Palestinian dwellers, as too scary and alien to visit.

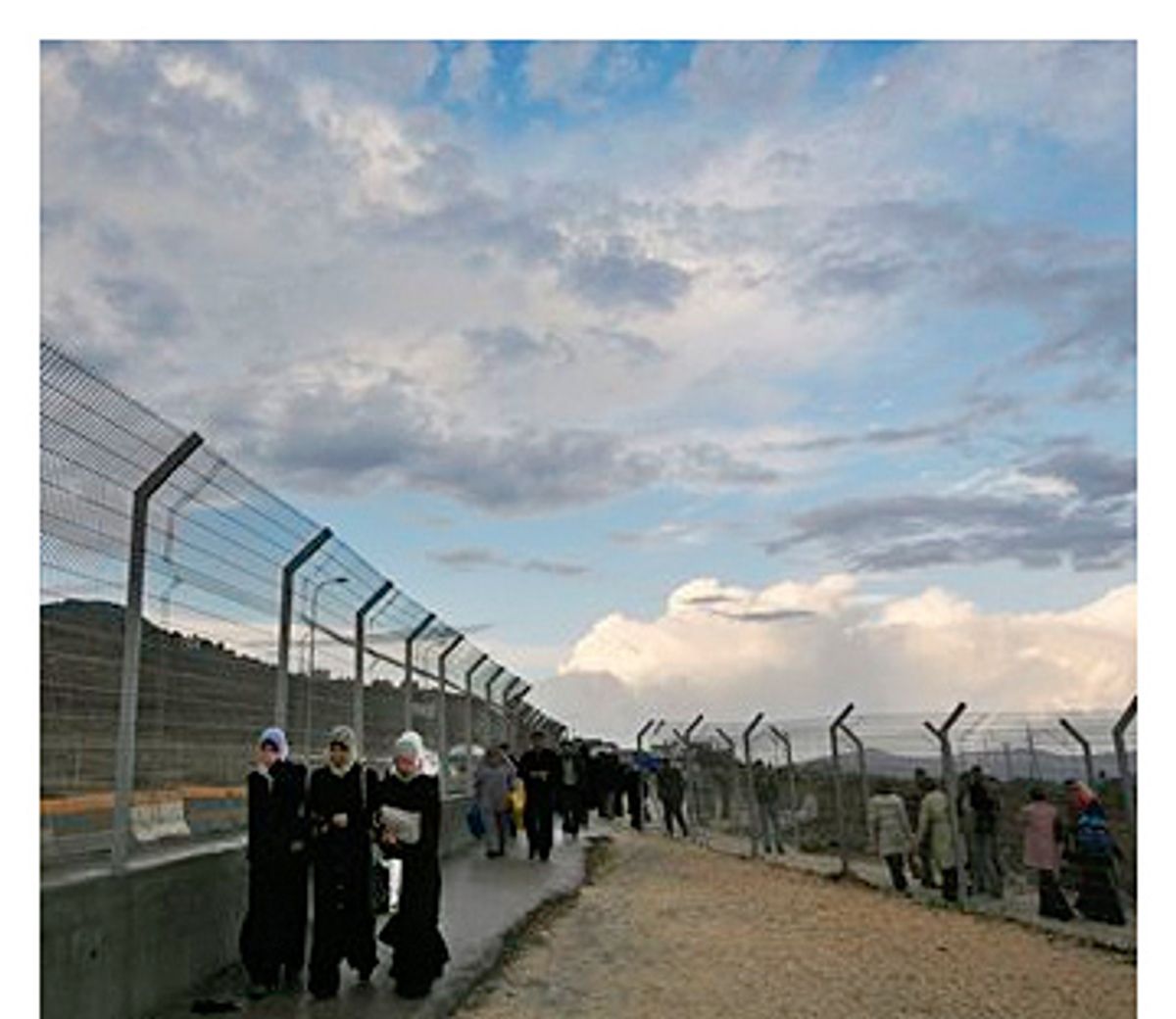

The truth is, the popular divorce that has hardened in place between Israelis and Palestinians has an acute political meaning. If you don't ever go to the West Bank or Gaza except for military duty, then for all practical purposes those places lie across the border. Official state or not -- it doesn't matter. Only diehard leftists and peace process buffs here still talk about "the occupation." The majority of Israelis, who never witness its ugly expressions -- the checkpoints, the travel bans, the house demolitions -- hardly bother to think about the occupation anymore.

This political parallax explains a paradox with Israeli public opinion. Polling data indicate strong support among Israelis for the establishment of a Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza. Yet, this majority support has not translated into action. The last three Israeli prime ministers -- Ehud Barak, Ariel Sharon and the incumbent Ehud Olmert -- have declared that Palestinian statehood is in Israel's interest. In reality, however, its establishment appears as remote as ever. The West Bank is ruled by an ad hoc hybrid: Israeli security forces, who also control the external borders; Israeli settlers and their municipal organs; the dysfunctional Palestinian Authority, which delivers civilian services; and Palestinian terrorist groups. Gaza is now controlled by Hamas, but with Israel essentially controlling basic services like food and electricity. It's a complicated mishmash, a patchwork of authorities and responsibilities. But, as destitute as parts of the Palestinian areas now are, to most Israelis the situation appears to be working somehow.

From the perspective of most Israelis, then, "if it ain't broken, don't fix it." Supporting Palestinian statehood in principle, and voting for it in public opinion polls, cost nothing. But why bother paying the costs of actually implementing the two-state solution if it already exists de facto? An Israeli withdrawal from the West Bank, a prerequisite for a Palestinian state there, mandates the relocation of tens of thousands of resistant settlers, who could disrupt public order and even turn to violence. It also means that the Israeli military would have to cede control of hills overlooking Israeli population centers and an international airport, exposing them to Palestinian militants' rocket fire and suicide bombers.

Under these circumstances, changing the status quo is hardly appealing, for better or for worse.

The detachment of Israelis from the occupied territories has not been only a voluntary reaction to Palestinian anger, violence and deadly terrorist attacks. It has been a deliberate government effort. In the past 15 years, all Israeli governments have implemented a policy of "separation," aimed at distancing and shielding the bulk of Israeli society from the unpleasant reality beyond the Green Line.

On May 24, 1992, Fouad el-Umarin, an 18-year-old Palestinian from Gaza, attacked Helena Rapp, a 15-year-old Israeli student on her way to school in Bat Yam, near Tel Aviv, stabbing her to death. At the time, Israel was only weeks away from a crucial election, in which Labor leader Yitzhak Rabin challenged the incumbent prime minister, Likud leader Yitzhak Shamir. Rabin pledged to create Palestinian "autonomy" in the West Bank and Gaza, while Shamir, the last believer in Greater Israel, favored keeping the territories under full Israeli occupation. His idea of responding to the first intifada was to build more Jewish settlements in the West Bank.

The murder of Helena Rapp was followed by three days of violent anti-Palestinian protest in Bat Yam. Mobs destroyed property and beat passersby who looked like Arabs. This gave the Rabin campaign an ace card. "We should take Gaza out of Tel Aviv," declared the former military leader, who held the respect of Israelis as "Mr. Security."

By August 1993, the newly elected Rabin signed the Oslo agreement with Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat. The Palestinian Authority, under Arafat's leadership, was formed in Gaza and parts of the West Bank, while Israel kept its overriding responsibility for security, including for the Jewish settlements there. Hamas, which opposed the peace process, launched a wave of terror -- first with knives and then with human bombs.

Rabin's response was to accelerate the separation process. Even before Oslo, his government declared a "full closure," forbidding Palestinians from entering Israel and working there. Then it built special roads for the Jewish settlers, saving them the unpleasant and increasingly dangerous drive through neighboring Palestinian towns. (In later years, Israel created two entirely separate road systems in the West Bank, forbidding Palestinians from using the "Israeli" roads.) A fence was built around the Gaza Strip, isolating it from Israel, which still kept more than 20 Israeli settlements on its other side.

These measures turned out to be irreversible. In a key shift, Israel began importing workers from Thailand, Romania and China to replace the Palestinians in the fields and on the scaffoldings. Independent from Palestinian labor, and more accepted globally, thanks to the Oslo peace process, Israel's economy geared itself rapidly toward the West and the new markets opened to it in Asia and the former Soviet Bloc. Its remaining ties with the dwindling Palestinian economy involved exports of basic products and services.

A second round of separation occurred under the leadership of Ariel Sharon, who took office in 2001. Sharon was a political pariah for many years, but his election was the response of angry and threatened Israelis to the collapse of the peace process and to the second intifada, which, unlike the angry stone throwing of the first one, exploded with weapons and suicide bombings. It was a first-rate historic irony that Sharon, an architect of the settlement project and Israel's long-term hold over the occupied territories, did more than his peers to scale it back. Facing the worst wave of suicide bombings in 2002, Sharon grudgingly agreed to build a security barrier to separate Israel from the West Bank. While its route, leaving about one-tenth of West Bank territory on the western, Israeli side remains controversial outside Israel, most Israelis view "the fence" as a blessing. Its construction coincided with a marked reduction in suicide bombings, which gave Israelis a renewed sense of security. More important, it created a physical division between the two sides. As it approaches completion today, it becomes increasingly impossible simply to cross the hills to the West Bank or vice versa.

In 2005, Sharon carried out his most daring endeavor, the "disengagement" from Gaza. He ordered the removal of all Israeli settlements and military posts, withdrawing to the pre-1967 line. While this move was supported by a majority of Israelis at the time, many had second thoughts later, when the evacuated area turned into a bastion of Hamas supporters and a basis for rocket attacks against Israeli border towns and villages. Nevertheless, the disengagement sealed Gaza behind high fences, and in the past two years, Israel has sought to cut its remaining ties and responsibilities there. The government declared Gaza "a hostile entity" and marked the crossings as border points.

The ever-increasing separation measures, the economic independence from the Palestinians and above all the physical barriers have isolated Israelis like never before from the "other side." This has enabled Israel to flourish as a first-world, Western wannabe, an enclave in the heart of an otherwise largely stagnant Arab world.

But this situation comes with a price. While allowing Israelis to ignore their unfriendly neighborhood, and live under the illusion that their country exists somewhere in Europe or North America, the status quo reduces Israelis' motivation to seek compromise and peace with the Palestinians. To observers of the Palestinians' deteriorating situation in the occupied territories, that symptom of Israeli denial can appear morally repugnant. And as the destitution in those areas mounts, the status quo is not likely to be sustainable -- a deeper chaos could erupt and become a much greater problem for Israel's government and people.

Perhaps most significant, the hardened status quo hinders the Jewish state's eventual acceptance in the Middle East, already a difficult goal. When Iran and its proxies aim to undermine the legitimacy of Israel, and even actively pursue its destruction, self-imposed isolation by Israel may be one of the biggest dangers of all.

Shares