"The Hall of Fame is a self-defining institution that has by and large failed to define itself," baseball guru Bill James wrote 13 years ago in his book "Whatever Happened to the Hall of Fame?" Never were his words more relevant than earlier this month when for a third time, Marvin Miller, retired leader of the Major League Baseball Players Association, failed to win election to baseball's secular shrine in Cooperstown, N.Y. Miller had come close in a vote two years ago when the veterans' committee was made up of more than 60 living Hall of Fame players. Led by New York Mets immortal Tom Seaver, the group still couldn't muster the 75 percent required for election. This time Miller's loss was unsurprising, given that the new 12-man veterans' committee was heavily weighted toward management and Miller was and is the ultimate spokesman for baseball labor.

The shock was that former commissioner of baseball Bowie Kuhn was voted in. During Kuhn's tenure from 1969 to 1984, he lost every significant battle he fought. Under Miller's leadership, the players' union finally ended the grip of the century-old reserve system that had made a player the property of one team indefinitely unless he was traded, sold or released. The only possible argument for Kuhn's enshrinement is that under his watch baseball began televising the World Series at night, and baseball got rich. Baseball's coffers grew from a paltry $72 million in 1971 to $1.2 billion in 1983. And yet the Hall has honored a man who to his dying day insisted the only mistake he ever made was not overruling the arbitration decision that led to free agency in 1976 -- something Kuhn was not even legally capable of doing. Ever ready to speak his mind, Miller, still feisty at 90, called Kuhn's election "rigged" and an "embarrassment" to the Hall of Fame.

Miller's right -- but what is to be done? I say it's time to use the Kuhn gaffe to make the Hall of Fame live up to its original ideal. Before the Hall opened in bucolic Cooperstown in 1939, National League president Ford Frick, later baseball commissioner, said sagely, "We want to make it as difficult as possible to get into this Hall of Fame. We are not going to provide any automatic system for piling up additions."

Only the truly great should be honored, not the merely good or the well-connected. So I say let's start ejecting some of the pretenders who never belonged there in the first place. We already have a system to vote worthy people into the Hall of Fame; let's institute a system to throw the unworthy folks out.

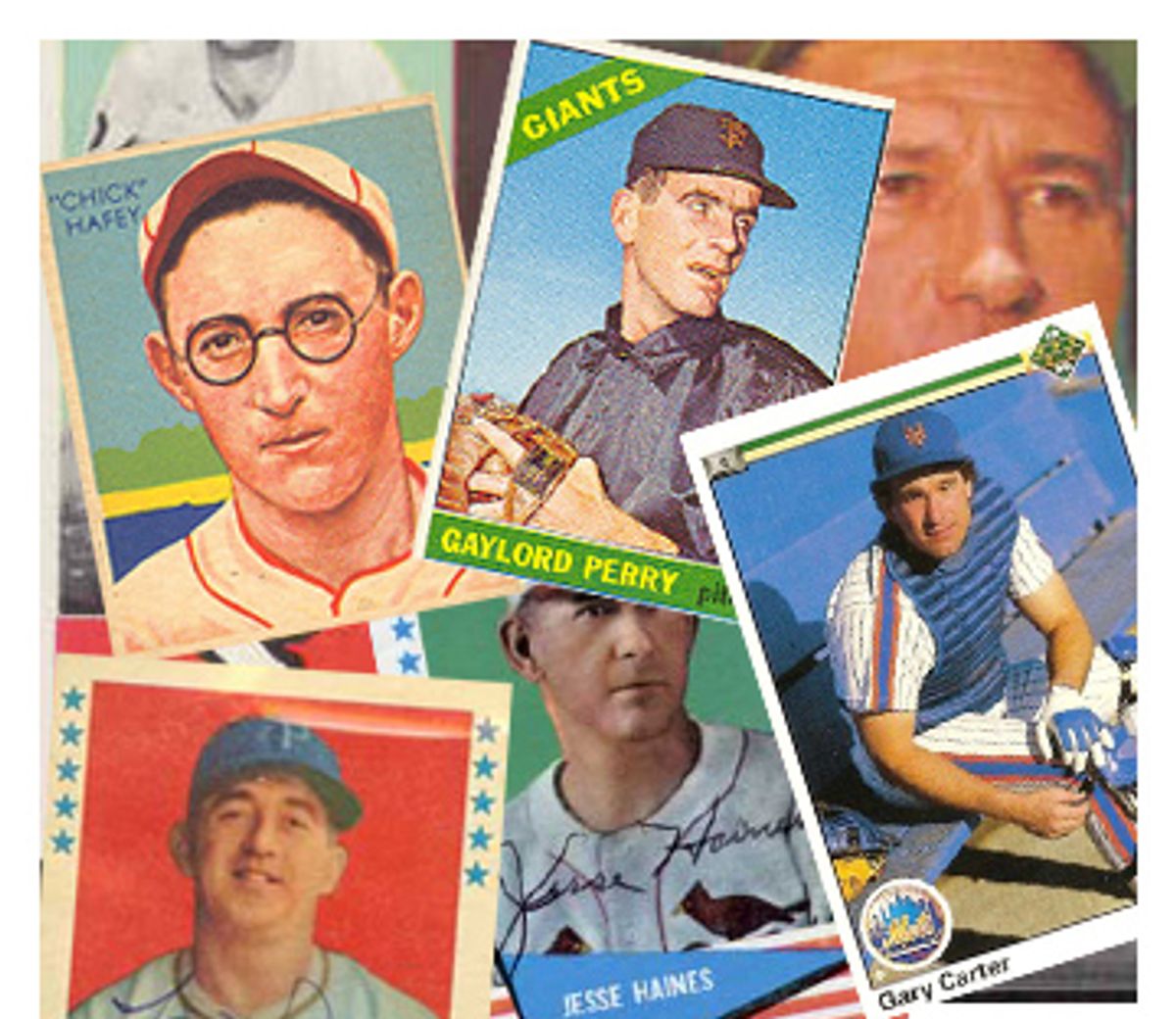

Like Gary Carter. Best known as a catcher for the world champion 1986 Mets, Carter was a straight arrow who loved the media so much that he was nicknamed "Lights" by his teammates. He hung on for 19 seasons in order to go over 2,000 career hits, a plateau often considered a requirement for election to the Hall. Sorry, Gary, but you led the National League only once in any offensive category, and your defense wasn't extraordinary. You were a soft touch for base stealers; besides "Lights" and "Kid," another of your lesser-known nicknames was "Rag Arm." You benefited from playing in the media capital of the world and on a charmed team. Off the island with you.

Or, backing up a half-century, let's bounce the teammates of Frankie Frisch. The Fordham Flash, who played for the St. Louis Cardinals and New York Giants in the 1920s and 1930s, was himself a no-brainer choice for the Hall of Fame. He had a .316 career average, amassed 2,880 hits, played in eight World Series, and was regularly listed among the league leaders in runs, hits and stolen bases. He was also a World Series-winning player-manager. But in his role as an "old days were the best days" curmudgeon on the Hall of Fame's veterans committee, Frisch shamelessly lobbied the sportswriters for the inclusion of old pals whose stats and overall skills simply were not worthy. I am talking about Giants infielders Dave Bancroft, George Kelly, Travis Jackson and Fred Lindstrom. Back up the truck, and out with their plaques!

The same goes for Frisch's St. Louis teammates, slugger Chick Hafey and pitcher Jesse Haines. If Hafey had been healthy, he probably would have been deserving of a place in the shrine. A pitcher converted by baseball mastermind Branch Rickey into a potent slugger, Hafey suffered from a chronic sinus condition that hampered his eyesight and limited his longevity. Too bad, Chick, if frogs had wings they'd fly. Haines' problem was the reverse. It was only the length of his career that enabled him to reach a respectable number of 210 career victories. Out with both of them, I say.

There are more candidates for dismissal who snuck into the Hall while voters were blinded by reflected glory. Consider Tommy McCarthy, who played alongside Hugh Duffy, a genuine Hall of Famer who hit .438 for the Boston Nationals in 1894. The press dubbed them the Heavenly Angels, but McCarthy's numbers were decidedly earthbound. Out the door, Tommy, and before you exit hold it open for another Bostonian, Harry Hooper, who played with Babe Ruth and Tris Speaker on four Red Sox pennant-winners in the 1910s. Ruth and Speaker were great players and deserved their place in the first 1939 induction class, but Hooper never ranked in the top of any league-leading offensive categories and he did not prevent enough runs with his defense to make up for his offensive mediocrity.

Rick Ferrell, time is up for you, too. You were a decent American League catcher from the 1920s to the 1940s but simply surviving in the big leagues for 20 years doesn't make you Hall-worthy. If your brother Wes Ferrell had seven more wins to reach 200 he'd have been a better candidate, but his omission was the correct decision. Please join him on the sidelines with the good and very good but, alas, not great. Same goes for you, Joe Tinker. Being the shortstop in Franklin P. Adams' poem about "Tinker to Evers to Chance" doesn't qualify you because you weren't as great as your teammates.

Hall of Fame handymen! Get your tools ready to remove the plaques of even some 300-game winners. Like Early Wynn, who made the Hall with a 300-244 record by limping in with three sub-mediocre years at the end of his career. He finished with a hardly stellar 3.54 earned run average. And do you think that a guy in the top five in career walks is a Hall of Famer? Give me a break! And as you leave, Early, hold the door for Gaylord Perry. His 314 wins look good on paper as does his respectable 3.10 ERA, but he also ranks in the top five losers in baseball history. He racked up 265 defeats before retiring in 1983. Is that a Hall of Fame standard? No way. Perry also cheated, throwing the spitball for much of his career. He even titled his autobiography "Me and the Spitter." If the Hall of Fame bans Pete Rose for betting on games and has so far spurned Mark McGwire for his alleged use of illegal substances, then how can Perry the blatant cheater remain in baseball's pantheon?

The same goes for Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher Don Sutton, who won 324 games but lost 256 -- more than Early Wynn! -- despite being on good teams. Sutton also scuffed the ball and did other things not worthy of a Hall of Famer. Out with them, I say, out with them all.

How will they be voted out? The way the system works now, print reporters pick the new inductees. Early in 2008, the Hall of Fame will announce which players if any will be voted in for induction in July by more than 500 sportswriters. The writers qualify by covering the baseball beat for more than 10 years. Rumor has Red Sox slugger Jim Rice and one-time Yankee relief ace Rich "Goose" Gossage having good chances to make it. I'm dubious about Gossage, who hung on at the end of his career to improve his numbers. But I don't have a vote nor, incredibly, do the radio-television beat reporters and sportscasters who see as many games as the writers. The current system is better than the management-skewing cabal that selects old-timers, but it could stand improvement.

In "Whatever Happened to the Hall of Fame?" Bill James made the admirable suggestion that future membership in the pantheon should be decided by members of five groups. One group would still be the media, but that would be expanded beyond print. The other four would be baseball executives and other industry professionals, players with at least 10 years' experience (including minor leaguers), fans and scholars. I'd qualify for the last two groups, so I like the proposal already, but why not expand it to let voters consider candidates for expulsion as well as candidates for inclusion? When four of the five groups are in agreement, the player or non-playing baseball notable is either added to the Hall -- or expelled.

How would the news of someone's de-election to the Hall of Fame be broken? How would you like to be the publicity person at the Hall of Fame delivering the bad news to the family of the evicted Hall of Famer? "Uh, uh, this is Cooperstown calling," I imagine the unfortunate flack who picked the short straw beginning, "Um, we have some regrettable news. Would you like us to mail you the plaque COD or will you pick it up in person?" It will be a tough call to make, but if the Hall of Fame is to live up to its ideal of excellence and not just anointing the merely good, someone will have to do it.

While we're at it, let me make one more modest proposal. The plaques themselves, the ones that remain in the Hall, need a serious rethink. How about resculpting them? I have never once, in many trips to the Hall of Fame, seen a bust that remotely resembled the real player. Please, Cooperstown, pare down your hallowed halls and upgrade the visages of those who remain! You have only the withering bonds of mediocrity to lose, and a world of true baseball gods to gain.

Shares