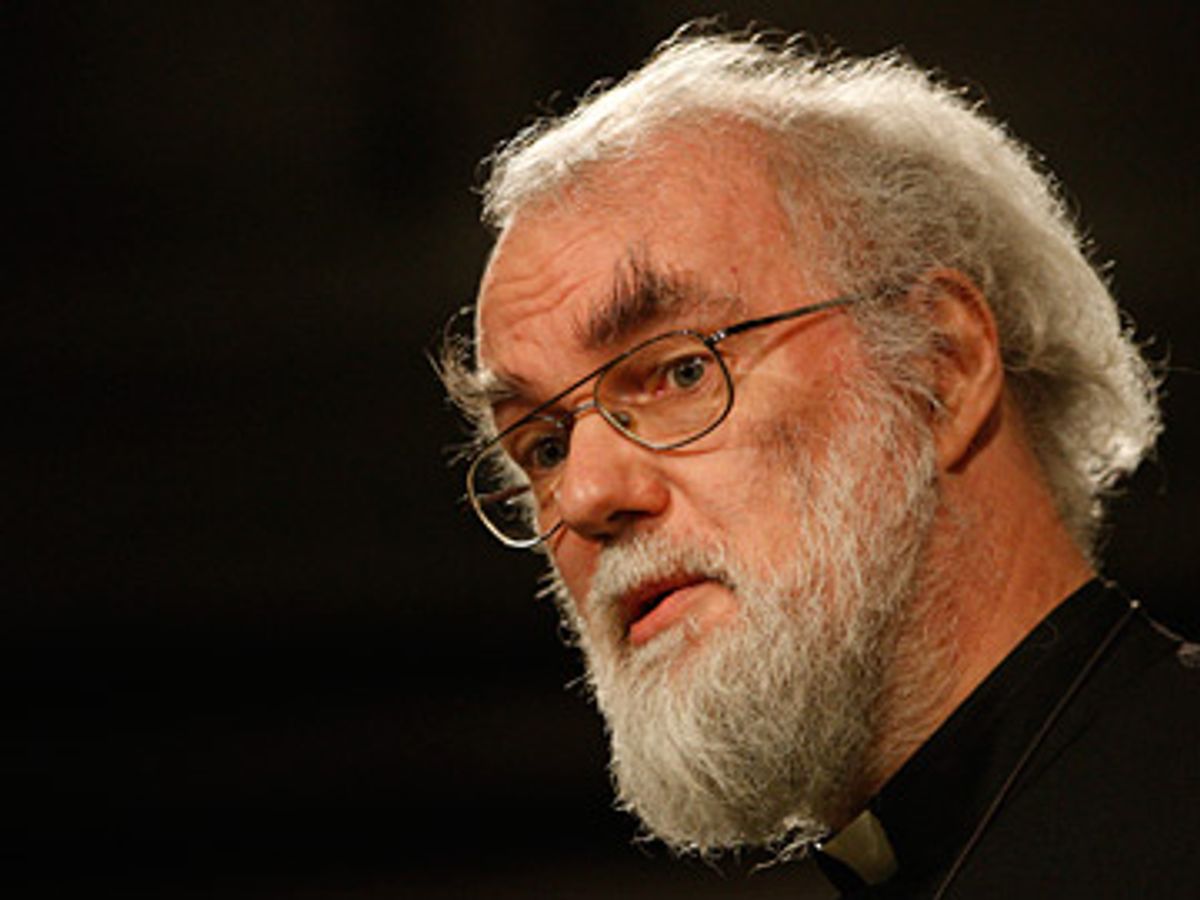

Five years ago this week (Feb. 27), Rowan Williams, 57, was enthroned as the 104th archbishop of Canterbury, heading Britain's official church, enjoying the privilege of being perceived as the moral authority of the government. When the queen is called the defender of the faith, that faith is the Church of England, and Williams is its CEO, with the church having the right to sit in Parliament. He is also the first among equals of the larger Anglican faith, with millions of adherents around the world.

And yet, if celebrations of the anniversary are subdued, he should hardly be surprised. In an address at the royal courts of justice, and in a radio interview, Williams suggested it was inevitable that Britain would have to accommodate aspects of the sharia law to help "maintain social cohesion," perplexing, dismaying, puzzling, upsetting and angering many in Britain and beyond. Williams said he wanted Britain to avoid the "inflexible or over-restrictive application of traditional law," and be wary of a "universalist Enlightenment system," which could ghettoize minorities.

This caused an immediate uproar: The government called his remarks "unhelpful"; his predecessor as the archbishop, George Carey, felt Williams' position as the church's head was now untenable; feminists condemned him for supporting faith-based traditions that undermine women's rights; tabloids asked for his removal. Ironically, among his enthusiastic backers was the fundamentalist Islamic group, Hizb ut-Tahrir, which seeks the revival of the Caliphate, and which is banned in much of Europe but is legal in Britain.

And so we have come to this. With his penchant for colorful robes, his majestic, graying beard, twirled eyebrows and occasional funny hats, Williams could be mistaken for Gandalf, if you ignore the crucifixes surrounding him. But make no mistake: While his tone may be gentler than that of an ayatollah, in the end, like all imams, he is cut from the same cloth.

At heart, the archbishop's deliberately ambiguously drafted speech is an attack on Britain's growing secularization. Churchgoing is in long-term decline in Britain, as it is in much of Europe. Internationally too, his authority is questioned, and the Anglican Church is on the defensive; it faces a real split following the election of a gay bishop in New Hampshire in 2003. Several bishops from Africa are boycotting the decennial Lambeth Conference this July.

Williams needs a creative way to assert his authority, and he thinks he can do it by pleasing everybody. And so, while he accepted this January that Britain's blasphemy laws would be repealed, he has also called for new legislation to outlaw cruel speech that hurts believers of all faiths -- whatever that means. Repealing the blasphemy law is a decision long overdue, at least since 1989, when Muslims correctly pointed out the double standard, where the state would not prosecute Salman Rushdie for writing the novel "The Satanic Verses," but retained the power to go after those who blaspheme Christianity. The state should, of course, leave both Rushdie and Monty Python alone.

This goes beyond speech: Some religious charities here do not want to allow gay couples to adopt children under their care, even though they draw money from the public purse. Since Britain adopted the European human rights charter, all forms of discrimination are outlawed, forcing such charities to choose between the law and conscience.

Williams has reasoned that anything that undermines one religion's role in the secular space undermines all. Even if, as in some instances, that "anything" is universal human rights. The official faith must, then, support its right to discriminate. This means Williams would prefer the inevitability of the sharia over the inevitability of separating the church and the state. (Such a separation has serious financial implications for Williams: His church controls nearly a third of Britain's state schools, paid for by all taxpayers, with or without faith.)

Williams says plural jurisdiction already exists, pointing out the Jewish beth din. But the beth din is voluntary (and feminists question if it is equitable to women), and it applies only in certain disputes under the civil law. Sharia's militant adherents, on the other hand, claim it applies everywhere, all the time, in all instances. To be fair, Williams did not endorse sharia's criminal law -- which includes stoning, public hanging and amputations. But the problem is that for the fundamentalist Muslim, the sharia is a seamless whole. It does not allow cherry-picking.

And this assertion of the sharia's seamlessness is exactly the problem. Can the sharia be reinterpreted to fit modern times? Does it require the stoning of adulterers? Do women victims of rape have to produce four male witnesses? Even so, does that make it right? Are all the hadiths really what Mohammed said, or did some clerics invent a few to maintain their control? With so many doubts, can a multifaith country require a group of its citizens to live under different rules, many of which might undermine human rights?

All disputes don't have to end up in courts. There is value in alternate dispute settlement mechanisms, and a case can be made for the advantages of settling family disputes in culturally appropriate ways, particularly where the language is a barrier, distrust of the state runs deep, and its instruments of justice are not easily accessible.

But the fact is that even in civil matters, sharia can be catastrophic for women. Take free consent, the cornerstone of any parallel judicial system. How does one explain the idea of free consent to a 19-year-old immigrant Somali bride who can't speak English, who is abused by her husband?

This is what horrifies many Britons, including many Muslims. With characteristic equivocation, Tariq Ramadan, controversial Islam scholar, said such statements "feed the fears of fellow citizens." But the fears are valid. As lawyer-activist Pragna Patel argues, Williams should avoid framing this debate "as if black and minority people can't claim ownership of the human rights principles and norms that now underpin the English legal system. At best, (he) is dangerously misguided in his attempt to assert a tolerant liberalism. At worst, he seeks to shape a larger agenda in order to privilege all religionists."

The archbishop's speech is another example of British multiculturalism gone crazy. Under multicultural pretexts, abuses are being tolerated. In some cases nurses have not reported instances of female genital mutilation, because that horrific practice is deemed to be a local custom of immigrants. Social workers have ignored women who may be victims of domestic violence, assuming if they interfere they'd be accused of being racist. Lawyers like Patel spent years fighting this and got the state to call forced marriage a crime, so that the state would protect British-born women being married forcibly -- sometimes over a phone call -- to men they had never met, who lived in Pakistan or Bangladesh. And if the women refused, in some cases their own relatives have killed them. A recent report from the think tank Centre for Social Cohesion shows many of these crimes continue.

Indeed, there are many Britains, and there is a parallel universe, which Rushdie described memorably as "a city visible but unseen." (At 1.6 million, Muslims account for 2.8 percent of Britons, with a large majority of them from Pakistan and Bangladesh; and among Britain's Asians, they constitute nearly two-thirds of the population.) They became visible when they burned copies of "The Satanic Verses." A group called the Muslim Council of Britain was formed, drawing on arch-conservative ideas drawn from fundamentalist groups in Pakistan. The council spends disproportionate time critiquing British and American foreign policy, compared to the problems of Muslims in British inner cities.

The uneasy calm between the British state and its Muslim population was shattered when former Prime Minister Tony Blair joined the U.S.-led war on terror in 2003. On July 7, 2005, four suicide bombers blew themselves up in London's underground subway system, killing more than 50 people. When Gordon Brown took over as prime minister last year, he was greeted with a failed plot to blow up an airport in Scotland and nightclubs in London.

Politicians have repeatedly stressed that the war on terror is not about Islam. Britain, with its history of "Troubles" in Northern Ireland, knows this only too well. Britain quite rightly accommodates many legitimate religious needs of its minorities. Adult Muslim women can wear the veil and, assuming they want to, Muslim schoolgirls can wear Islamic uniform in state schools (unlike in many French state schools). Most workplaces are sensitive to meal breaks and prayer times during Ramadan; some even build prayer rooms -- a concession rarely granted to other faiths.

But in very real ways, Britain is bending over backward. While polygamy remains illegal, the government permits it, providing welfare benefits to a man's multiple wives, in effect endorsing an illegal practice. When a think tank exposed the MCB's links with radical Islamic groups, and how it was influencing the government's thinking, the government's response was to charge the civil servant who leaked the story. The case collapsed. In 2004, at taxpayer expense, London's leftist Mayor Ken Livingstone welcomed to his city the controversial Egypt-born cleric Yusuf al-Qaradawi, who has called gays "perverts" and backed suicide bombers in Israel.

In significant ways, the British state has been crawling when it was not even asked to bend. And Britain's multiculturalist liberals see virtue in newly discovered supine poses that can't be found in any yoga book, and can even harm their way of life. Recently, novelist Martin Amis was speaking to an unreceptive audience at an arts center about his new book, "The Second Plane," which collects his writings highly critical of radical Islam. He asked the audience how many of them felt morally superior to the Taliban. He was taken aback: Barely a third of the hands went up, even though the Taliban would have destroyed the building and its surroundings -- with the alcohol in its bar and risque art on its walls, with the sylvan St James's Park on its side, where during long summer afternoons, lovers wearing little lie on the grass wrapped in one another, and with the West End minutes away, where the odd play may have frontal nudity. And yet, Amis recalled, his audience could not say it felt morally superior to the Taliban.

This is the environment that emboldens Williams, where the sharia becomes his useful ally. If customary laws derived from some myths are to be secondary to secular laws, what happens to practices drawn from other myths? Hence his concern; hence he must defend all faiths -- even if that undermines equality before the law.

Shares