History, in Marx's famous dictum, tends to repeat itself: the first time as tragedy and the second time as farce. So what do you call it the third time around? A bad sitcom? A bad marriage? A bad dream? All three of those seem like viable ways of describing the Democratic Party's current predicament, locked in an endless and self-destructive struggle with itself, like a would-be Buddhist penitent unable to atone for eons' worth of bad karma.

Even in the annals of Democratic ritual suicide, the 2008 campaign is something special: It's not just that the protracted and painful nomination struggle between Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton repeats all the classic themes of intra-Democratic conflict -- left vs. center, reformer vs. the Establishment, pragmatist vs. idealist, call it what you will -- up to and including the fact that the differences between the candidates are mainly semiotic rather than substantive.

In his recent Salon article, Michael Lind identifies the split between dueling Democratic wings of the 1950s, specifically between hard-headed pragmatist (and Cold War hawk) Harry Truman on one side and liberal idealist (and Cold War dove) Adlai Stevenson on the other. Like almost any comment anybody makes about this split, that's an invidious comparison, and Lind is clearly advocating one side of the equation. Truman won an election as the nominee of a divided party (against the odds) and Stevenson lost two of them (against even greater odds). But let's let that stand, since Lind's dating of the emergence of this division is clearly correct: The last president to command enthusiastic support from all sides of the Democratic coalition was Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Before this year's historic campaign, poisoned at the root by overt and ugly sexism and covert and coded racism, Democrats have never been asked to choose quite so nakedly which absolutely necessary demographic they would like to do without. Here is the question, a cynic might suggest, that the Democratic Party must answer this summer: Do we want to lose because we drove away blacks or because we drove away white women? (Recent polling data suggests another cynical question: Do we prefer the candidate Americans believe is a liar or the one they believe is a Muslim?)

We've all seen this movie before, whether we realize it or not. If we're not quite sure how it's going to end, the characters and situations all seem strangely familiar. Beginning with the debacle of 1968, every Democratic campaign for four decades has followed pretty much the same template, even if the labels have shifted with the tide. The quadrennial conflict between liberals and moderates, outsiders and insiders, let's-win-an-election realists and let's-save-our-party dreamers -- supply your own dichotomy here -- reflects the fatal uncertainty of a political party that lacks any clear constituency or ideological focus. Even as the Democratic Party encompasses the views of a plausible majority of the population, its unresolved internal struggles have time and again undermined its ability to win elections or (when it happens to stumble to victory) to govern effectively.

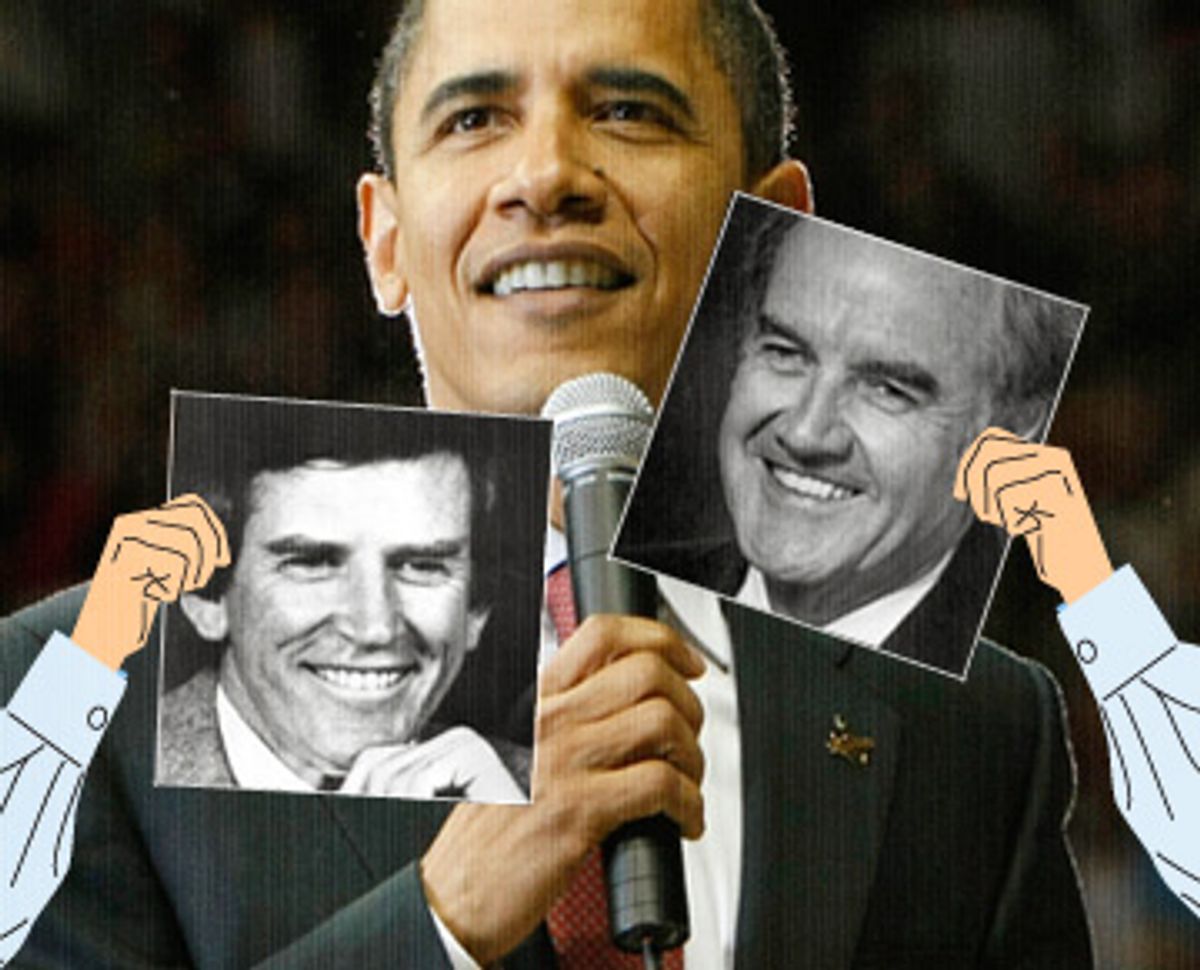

To get specific, the 2008 Obama-Clinton contest offers eerie echoes of two of the most traumatic -- and defining -- campaigns of recent Democratic history. Neither of them is likely to give party faithful the nostalgic warm fuzzies. First, and most explosive, there's the comparison increasingly drawn on the right (and lately among a handful of Democrats) between Obama and Sen. George McGovern, who played the paradigm-shaping role of reformist outsider in 1972. Of course it's meant to be a toxic metaphor, suggesting that Obama is a dewy-eyed Pied Piper leading his followers into a November electoral catastrophe. Let's set that silliness aside right now. Whoever the Democrats nominate will not be facing a popular incumbent but an awkward Republican nominee who has embraced an unpopular war and remains unloved by his own party's base. One should never underestimate the Democratic ability to lose elections, but ain't nobody carrying 49 states this fall.

Get past that, though, and the McGovern parallels are seductive. The South Dakota senator was a heartland American from central casting -- a preacher's kid turned decorated bomber pilot turned Methodist minister. McGovern was far from the most leftward candidate in the race, which in its early stages included antiwar veteran Eugene McCarthy and black New York congresswoman Shirley Chisholm. As Hunter S. Thompson describes the field in his legendary "Fear and Loathing: On the Campaign Trail '72," McGovern initially appeared earnest, sincere and not especially ideological. Many left-wing activists saw him as too mainstream (a charge that was not much heard later). But his left-populist views, notably the fact that he had opposed an unpopular foreign war almost from its inception, meant that he began his long-shot 1972 campaign supported by a burgeoning nationwide network of young, liberal volunteers.

In early primary and caucus states, it was McGovern's superior ground-level organization that ambushed Sen. Edmund Muskie, the Establishment-backed, well-funded front-runner. In fact, McGovern and his campaign manager (a young man named Gary Hart, about whom more later), often credited as the men who put the Iowa caucuses on the political media map, devised a strategy to win them based on a committed core of activists rather than a broad base of support.

Muskie was widely seen as more experienced, more responsible and more electable, but was also widely loathed by younger and more liberal voters because of his views and voting history on -- yes -- a controversial overseas war. To coin a phrase, Muskie was for the Vietnam War before he was against it. As the running mate of the 1968 Democratic nominee, Vice President Hubert Humphrey, Muskie had kept silent while Humphrey struggled to justify Lyndon Johnson's massively unpopular escalation of the war. By 1972 everyone in American politics (including incumbent Richard Nixon) wanted out of Vietnam, and early in the campaign Muskie held a press conference where he apologized for his previous views and pronounced himself a born-again antiwar candidate.

Thompson observes that Muskie's awkward public apology put him permanently on the defensive against McGovern, who had opposed the war vigorously since 1964. (Actually, he had voted for the Gulf of Tonkin resolution that year, but recanted his support a few months later after learning that the alleged attack on two American destroyers was, in his words, "a total fiction.") You can bet the ranch that someone in Hillary Clinton's campaign -- quite possibly the candidate herself, who was a McGovern volunteer in Texas, alongside her Arkansan boyfriend -- has reflected on the Muskie debacle and vowed to avoid any public apology.

With younger antiwar voters flocking to McGovern on the left and Nixon's dirty-tricks squad sabotaging him from the right -- Republican operatives apparently concocted a letter alleging that Muskie had laughed at a derogatory comment about French-Canadians (!) -- Muskie may or may not have broken down in tears during a New Hampshire news conference. But male Granite State tears in 1972 do not have the same sociocultural resonance as female Granite State tears in 2008, it seems. Seen as emotionally unstable and losing ground rapidly, Muskie was driven from the race.

After Muskie's departure, the role of the Establishment candidate fell once again to Humphrey, the man who had captured the 1968 nomination without winning any primaries or pledged delegates. At that point, most Democratic delegates were the kinds of party apparatchiks we would today call superdelegates, and in fact it was a commission led by McGovern that redesigned the nominating process for '72 such that primary voters would play the decisive role. While the system worked as designed -- McGovern won the most primary delegates and captured the nomination in the end -- the race went all the way to a floor fight over delegate credentials at the Miami Beach convention, partly because (ironically enough) the more moderate Humphrey had won a slight plurality of the Democratic popular vote.

Even if you weren't alive or conscious in 1972, you don't need me to tell you what happened in the fall election, or to expound on its significance. If the McGovern race was the scourging tragedy whose marks the Democratic Party still carries on its collective body, then the 1984 contest between Walter Mondale and Gary Hart -- another primary season that stretched all the way to the convention, with superdelegates implicated in the final outcome -- was its farcical mirror image.

Despite whatever whispered comparisons between Obama and McGovern have circulated among a few McCain and/or Clinton supporters in recent weeks, the Illinois senator seems unlikely to make the kinds of risible political mistakes that doomed McGovern to a history-making wipeout. (He was never going to win, no matter what, but a respectable defeat in which McGovern carried 12 to 15 states might well have altered subsequent history.) Obama isn't going to give his convention acceptance speech at 3 a.m., and he won't select a running mate with a documented history of mental illness -- not to mention a running mate who turns out to be the source of the campaign's single most damaging remark. (As Bob Novak revealed last year, it was Sen. Thomas Eagleton who launched the infamous description of McGovern as the candidate of "amnesty [for draft dodgers], abortion and acid.")

What's at work here is the Democratic hierarchy's interminable and tiresome case of 1972-related PTSD, and its tendency, like a dog that's been mercilessly beaten, to internalize the worst behavior of its persecutors. Many Democrats fear (and a few hope) that Obama will be eviscerated as an America-hating Black Muslim al-Qaida agent and get wiped off the electoral map this fall. Be that as it may, Obama strikes me as much closer in tone and temperament to Hart, 1984's golden-boy outsider, than to McGovern.

Hart was McGovern's campaign manager in '72, and evidently learned both positive and negative lessons from that experience. He played a lite-beer version of the reform-minded progressive, with great taste and 80 percent less ideology. He promised a pragmatic, hands-across-the-aisle approach that rejected Mondale's old-school partisan politics and "failed policies" in favor of unspecified "New Ideas." Although the word "yuppie" had appeared in print as early as 1982, it first achieved widespread currency as a descriptor for Hart's core demographic. Energetic and charismatic, Hart was a good speaker and a relatively young man in a political field dominated by jowls and gray hair. (He was 47 in 1984; Barack Obama is 46 today.)

Hart's opponent was more knowledgeable on foreign policy and more experienced with the machineries of Washington. Former Vice President Mondale had done time in the Oval Office, offering the president sage counsel in times of crisis. He was a known and trusted figure to working-class white voters in the Rust Belt states. In fairness, the electoral map of the Hart-Mondale race looks almost like the Obama-Clinton contest in reverse, which may reflect a lack of clarity over which '84 candidate was the liberal and which the moderate. Hart won many of the big prizes -- including Massachusetts, Florida, Ohio and California -- but was outspent and out-organized in numerous Eastern and Midwestern states.

Still, the odd feeling of déjà vu persists. After Hart became the surprise front-runner, he faced heavy media scrutiny and had to weather a few minor scandals that suggested a "flake factor" in his personality. (He had changed his name, his birth date and his signature, and had twice separated from his wife -- but the Donna Rice scandal did not erupt until 1987.) His close and acrimonious contest with Mondale zigged and zagged and was endlessly dissected by the media for its sociological and generational significance.

By the time the two candidates reached the San Francisco convention, Mondale was virtually assured of the nomination, but it's worth noting why that happened. If the '84 election had been conducted under the "McGovern rules" of 1972, the duo would have hit the summer solstice virtually tied in pledged delegates. But in the intervening years, a balance of power had been restored to party leaders through an arcane delegate-selection process, and a new term had been invented. Mondale's victory came not because he zinged Hart as a lightweight by asking "Where's the beef?" in a memorable debate moment (although that helped) but because most of the party's Establishment superdelegates had been in his camp from the beginning.

The end of the story was depressingly familiar, but nobody ever reflects on the fact that Mondale's defeat by Ronald Reagan was nearly as bad as McGovern's 1972 loss to Nixon. (In Electoral College terms, it was even worse.) It's fair to say that the Democratic leadership is always more eager to lose with a Mondale than with a McGovern -- with a familiar, safe, mainstream candidate rather than a reform-minded outsider. Certainly the 1984 result produced little of the ritual self-excoriation and rending of garments that followed 1972; and while Mondale is among the party's respected elder statesmen, McGovern remains pretty much a pariah. You'll never hear anyone ask with terror in his voice, "Good God, is this guy another Fritz Mondale?"

But here's the real point: In both campaigns, supporters of whichever Democrat had lost the intra-party conflict felt aggrieved by the end result. In 1972, moderates believed that Humphrey (or Muskie) might have stanched the outward flow of working-class heartland Democrats and triangulated his way into a close race against Nixon. On the other side of the coin, the burgeoning bicoastal yuppies of 1984 were convinced that the younger, brighter, more vigorous Hart would have offered a stronger contrast to the geriatric and increasingly befuddled Ronald Reagan. I don't claim to know whether those alternative scenarios could have borne fruit (it seems dubious in both cases), but the result was more intra-Democratic bitterness and bad karma, as the dessert topping to humiliating defeat.

As is true again in 2008, ideology plays no more than a supporting role in these contests. Certainly there were political differences between McGovern and Muskie/Humphrey, although the former was never the Ho Chi Minh-loving, acid-eating radical of Bob Novak's wet dreams, and their policies as president wouldn't have been all that different. With Hart and Mondale, as with Obama and Clinton, ideological distinctions are almost invisible, and one could argue that the older, Establishment candidate in each pair is actually closer to old-line Democratic liberalism than the younger reformist.

These conflicts are about other things. Like every other American consumer experience, they're about affect and manner and first impression, and similar elements of unconscious psychological response. (Who you want to have a beer with, for example, or who reminds you of which of your parents.) As Lind would have it, they're about class and geography and certain unrecognized elements of American tribalism, although I find his insistence that the ancestral roots of white voters still plays a role in this most ahistorical of nations pretty bizarre. In this Democratic race and the two others I've discussed, the conflict is also clearly about age and generation and one's relationship to the recent historical past. This year's election, of course, is uniquely about race and gender, about the feminist revolution and the civil rights movement and their uneasy shared history.

But I don't believe that the Democratic Party's incurable case of schizophrenia can be boiled down to any single social or cultural factor. Lind's learned-sounding dissertation, casting Obama as the preferred candidate of moralistic Northern white Protestants in a "Greater New England" that stretches, apparently, from Maine to Oregon, is both overly broad and overly reductive, in the great tradition of half-baked social science. (In a piece that decries the perceived elitist tendency to mock working-class white Americans, Lind apparently feels it's OK to make fun of Wisconsin. My Waukesha County in-laws are up in arms.)

Maybe Lind is correct to imply that a multimillionaire senator whose voyage in life has taken her from an upper-middle-class Chicago suburb to a nosebleed-wealthy New York suburb, by way of the Arkansas governor's mansion and the White House, is an "extroverted, populist party regular" in the Truman mold, with an appetite for red-meat political struggle. Maybe her opponent, a mixed-race immigrant's kid who had a poor and peripatetic childhood (and, as recent estimates reveal, possesses about 5 percent of her net worth), really does fall on the Stevensonian side of the culture gap, "urbane, ironic, detached, introverted, intellectual and disdainful of petty politics." If that's so, it only reinforces my earlier point that American politics has become an entirely semiotic affair, a shadow play of gestures, codes and signals that long ago abandoned any relationship to material reality.

As Lind and many others may reply, there is an underlying reality here: Someone will carry enough states in November to win an Electoral College majority, and right now the Democratic Party is doing an outstanding job of ensuring that person will be John McCain. I won't bore you with my personal theory as to whether the liberal reformer or the Establishment moderate, in their 2008 incarnations, is more electable. Nobody knows. What we might laughably call the evidence is all over the place; the question can be argued in either direction and we're all bullshitting. I do, however, have a prediction of sorts: If Hillary Clinton remains within, say, 100 delegates and 100,000 popular votes after June 3, she will be the nominee. It's unlikely to be that close, but if it is, you read it here first.

Barack Obama remains the more plausible nominee, by far, and if he bears a certain resemblance to the primary-campaign version of George McGovern, he bears almost none to the general-election caricature crafted by Nixon's ruthless campaign. (Although I'm sure we will be hearing the comparisons.) He bears a stronger resemblance to Hart and perhaps, as his supporters would say, to John F. Kennedy, a young philosopher-king riding to Washington on his white charger. There are other, less heartwarming possibilities.

As a couple of my friends have suggested, Obama could also turn out to be the smooth-jazz remix of Michael Dukakis, another blue-state yupscale reformer who upended the Democratic primary season and emerged a surprise winner against better-known politicians. When the Donna Rice affair knocked Hart from the 1988 field, Dukakis inherited his mantle as the voice of a dispassionate, rational post-McGovern liberalism. Democrats from all regions of the country flocked to his unflappable, intellectual style, which belonged unmistakably to the Adlai Stevenson tradition. There was no incumbent in the White House, and after eight years of Reagan, conditions seemed ripe for a Democratic victory over George H.W. Bush, Reagan's aristocratic, ill-at-ease veep.

Dukakis sailed into the fall campaign with a Gallup Poll lead of as much as 18 points and seemed blissfully unable to respond when legendary Republican hit man Lee Atwater depicted him as a wimpy Massachusetts tax-and-spend liberal -- who had released a convicted murderer from prison so he could commit rape and armed robbery. (Said convict being Willie Horton, subject of the most famous attack ad in American political history.) Dukakis' disastrous photo op at the helm of a tank, wearing a too-tight helmet and a goofy grin -- as David Brinkley observed, he bore a striking resemblance to Rocket J. Squirrel -- sealed the deal. In absolute terms '88 was nowhere near as bad as '84 or '72 (Dukakis carried 10 states and the District of Columbia), but it remains the classic example of a Democrat snatching crashing defeat from the jaws of achievable victory.

Here's a trivia question for extra credit: Name the Establishment Democrat who was Dukakis' leading primary opponent. No, you get only half a point for Dick Gephardt, who dropped out early. That's right, in the back: It was a Tennessee senator, future vice president and global-warming guru, who won several primaries but never appeared viable outside the South. If we imagine for a moment that he had been the '88 nominee and daddy Bush had never been elected in the first place ... but that way lies madness.

I'm not arguing that Obama is doomed to suffer Dukakis' fate. For one thing, Obama is turning out to be among the best orators of recent American history, while Dukakis was a tedious policy wonk who kept audiences awake only because his nasal Boston accent was so irritating. I am arguing, though, that the Democratic Party is caught in an excruciating Catch-22 of its own making. Democrats are acutely aware that once they finally choose a candidate -- whether it's the reformer or the Establishment figure -- history offers many paths to defeat, and few to victory. But the tortuous indecision of the 2008 campaign (as in the '84 and '72 campaigns) may itself prove fatal.

When Lind writes that the Democrats' fate in November depends on healing "long-familiar regional and cultural splits among whites in the Democratic electorate," he's skipping directly over the central issue and arguing that his side (Humphrey-Mondale-Clinton) must prevail and the other side (McGovern-Hart-Obama) must capitulate. Here's what I mean by the central issue: It isn't flippant or metaphorical to describe the Democratic Party as schizophrenic. The ugly flame wars conducted between Obama and Clinton supporters all over the blogosphere, and not least on Salon's letters pages, reflect a deep pathology at the core of the party's identity.

To caricature the two groups only a little: One side embraces a tight and sweaty electoral calculus not much different from those of the Gore-Kerry elections, and seeks to focus on a meticulously triangulated blend of wedge economic issues and flag-waving patriotism that might siphon off a few hundred thousand moderate whites and Latinos in a few Midwest, Mountain West and not-so-deep South states. The other side wants to sweep the electoral map as clean as a Tibetan sand mandala, with the broom wielded by a magical figure pledged to purify the polluted realm of politics.

In my darker moments, I suspect that one side would rather lose a battle fought on the narrow ground they see as pragmatism and realism, rather than risk discovering that their starry-eyed opponents have a fairer and more generous vision of the country than they do. Conversely, the other side might actually prefer to go down in the flames of idealistic self-immolation, McGovern-style, rather than suffer through another Clintonian era of perennial compromise and constant dissatisfaction.

Even if the warring parties do not consciously feel that way, results speak louder than words: Excluding the Jimmy Carter "Watergate election" of 1976, Democrats have elected just one president since LBJ. And while Bill Clinton's economy looks pretty good right about now, let's remember that he lost both houses of Congress halfway through his first term, was virtually paralyzed by scandal in his second, and drifted toward social policies slightly to the right of Richard Nixon's. Then there was his wife -- what was her name again? -- who botched the issue of national healthcare so badly that it's been off the table ever since.

This intra-Democratic conflict is profound and epistemological. It speaks to deeply divergent ideas about the nature of politics, of America and indeed of human life. It dwarfs the so-called divisions in the Republican Party, which always seem miraculously healed by the time Election Day arrives. (You don't hear Mitt Romney's former supporters vowing to vote for Obama.) It isn't a battle for the soul of the Democratic Party; it is the Democratic Party. It is not likely to be healed anytime soon, whether or not this year's nominee can lure the semi-mythical gun-loving lumpenproletariat at whose feet Lind prostrates himself. It has robbed the United States of an effective opposition party for four decades, with no end in sight.

Shares