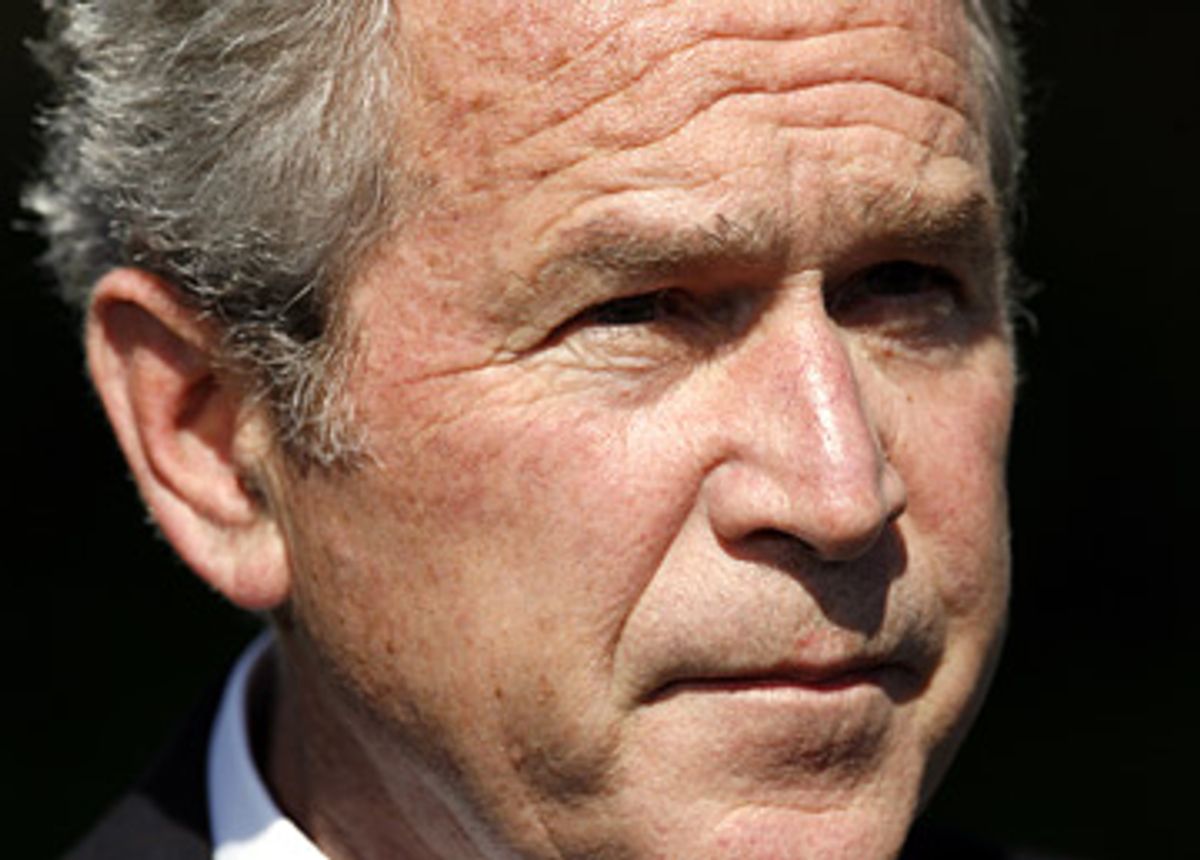

On July 3, Chief Judge Vaughn Walker of the U.S. District Court in California made a ruling particularly worthy of the nation's attention. In Al-Haramain Islamic Foundation Inc. v. Bush, a key case in the epic battle over warrantless spying inside the United States, Judge Walker ruled, effectively, that President George W. Bush is a felon.

Judge Walker held that the president lacks the authority to disregard the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, or FISA -- which means Bush's warrantless electronic surveillance program was illegal. Whether Bush will ultimately be held accountable for violating federal law with the program remains unclear. Bush administration lawyers have fought vigorously -- at times using brazen, logic-defying tactics -- to prevent that from happening. The court battle will continue to play out as Congress continues to battle over recasting FISA and possibly granting immunity to telecom companies involved in the illegal surveillance.

The story of how Al-Haramain's lawyers negotiated the journey thus far to Judge Walker's ruling -- a team of seven lawyers that includes me -- sheds light on how much is at stake for the Bush administration and the country. It is a surreal saga, involving a top-secret document accidentally released by the government, a showdown between Bush lawyers and a federal judge, the violent destruction of a laptop computer by government agents, and possibly even the top-secret shredding of a banana peel.

Call me Alice -- because this is a tale directly from Government Secrecy Wonderland, the bizarre and unnerving adventures of suing President Bush for apparently violating a federal law. I'll swear under penalty of perjury that what follows is true and correct. Otherwise, you might not even believe it.

The secret document

FISA requires a warrant for electronic surveillance inside the U.S. for intelligence gathering. President George W. Bush secretly violated FISA for nearly six years, starting shortly after the terrorist attacks of 9/11. FISA makes those violations felonious and provides for civil liability to the victims. I am one of seven lawyers in Oregon and California representing three of those victims in Al-Haramain Islamic Foundation Inc. v. Bush, a civil lawsuit against the president.

The plaintiffs are Al-Haramain -- a defunct Islamic charity based in Oregon -- and two lawyers who represented Al-Haramain in 2004 during proceedings by the Treasury Department's Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) to declare Al-Haramain a terrorist organization, the primary consequence of which was to freeze its assets. (This effectively put the organization out of business.) Of the four dozen lawsuits challenging various aspects of Bush's warrantless electronic surveillance program, the Al-Haramain case is unique because we have proof that our clients were actually wiretapped and thus can satisfy the legal requirement of "standing," or grounds to sue -- meaning we can show they were victims of the unlawful conduct for which they are suing. Nobody else has been able to produce such proof.

Our proof is a top-secret classified document, which the government accidentally gave to Al-Haramain's lawyers in August of 2004. We call it "the Document." It appeared in a stack of unclassified materials that the lawyers had requested from OFAC. Six weeks later, after the government realized its blunder, FBI agents personally visited each of the lawyers and made them return their copies of the Document. But the agents made no effort to retrieve copies that the lawyers had given to two members of Al-Haramain's board of directors, who lived outside the United States.

I can't publicly reveal what's in the Document because, well, it's a secret. I would be committing a crime -- a violation of the Espionage Act of 1917 -- if I were to do so. But we assert the Document as proof of allegations we have made that in March and April of 2004 the National Security Agency conducted warrantless electronic surveillance of attorney-client communications between a representative of Al-Haramain and two of its attorneys, and that in May of 2004 the NSA gave logs of those surveilled communications to OFAC.

The FBI vs. the judge

Along with the complaint (the formal pleading that starts a lawsuit), which we filed in February of 2006 in the Oregon federal District Court, we submitted the Document. The government's first response was to try to seize the Document from the court. On March 17, 2006, as we were holding our first all-hands meeting of the Al-Haramain legal team in Portland, we received a telephone call from a Department of Justice attorney, advising us that FBI agents were en route to the federal District Court building to confiscate the Document. We immediately lodged a protest with the assigned judge, Garr King, who scheduled an emergency telephone conference with him and all counsel. The FBI agents retreated.

During the emergency hearing, DOJ attorney Anthony Coppolino demanded that the Document be turned over to the FBI for storage in a top-secret repository called a Sensitive Compartmented Information Facility, or SCIF. To my astonishment, Judge King responded: "What if I say I will not deliver it to the FBI, Mr. Coppolino?" A clash of constitutional powers was brewing. Agents of the executive branch were threatening to invade the files of the judicial branch. The judge was resisting, almost daring them to.

It was the executive branch that blinked. After a pause, Coppolino said: "Well, your Honor, we obviously don't want to have any kind of a confrontation with you; we want to work this out." We all agreed that the Document would be held in a nearby SCIF to which Judge King would have free access.

This was the beginning of a bizarre journey that has not yet ended. Since then, for nearly two and a half years, we have been attempting to use the Document to confirm our clients' standing to sue under FISA and thus test the legality of President Bush's warrantless surveillance program. More broadly, we want the courts to discredit the so-called unitary executive theory of presidential power, which holds that the president has exclusive authority over matters of national security and may disregard laws like FISA that impose checks on presidential power. First, however, we have had to get past a major obstacle used by the Bush administration to stand in our way.

The state secrets privilege

The state secrets privilege, which is rooted in a 1953 Supreme Court case, allows the government to refuse in civil lawsuits to disclose classified evidence that is a state or military secret. In extreme cases, where the very subject matter of the lawsuit is secret, the lawsuit may be thrown out entirely.

Soon after the Document's place of reposit was resolved, the government asked Judge King to throw out our lawsuit pursuant to the state secrets privilege, a tactic used aggressively by the Bush government. We opposed that request, arguing that the Document isn't a secret any longer, since we and our clients have seen it. The government attorneys insisted that the Document is still a secret no matter who knows about it, and further insisted that the warrantless surveillance program itself remains secret -- never mind that the New York Times revealed the program in December of 2005 and soon thereafter the president publicly admitted its existence.

By this time, in a burst of healthy paranoia, we had destroyed all our copies of the Document, and the government wouldn't give us access to the copy held in the SCIF. What would Judge King do? It's no small thing for a judge to take on the president in matters of national security. Judge King came up with a compromise: In a ruling issued on Sept. 7, 2006, he denied the government's request, but also denied us access to the copy in the SCIF. Instead, he said, we could proceed to demonstrate standing by filing secret affidavits describing the Document from memory.

Laptop lunacy

The government lawyers appealed Judge King's ruling to the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals. But they blundered: They failed to file an immediate request to suspend the lower court proceedings that Judge King had authorized -- our showing of standing with secret affidavits describing the Document from memory. For two months we quietly worked on our written showing. By the end of October, having completed most of the drafting, all we had left to do was prepare our secret affidavits describing the Document from memory, along with a short supplemental secret brief explaining how the affidavits established standing. On Oct. 27, 2006, I flew to Portland from my home in Oakland, laptop computer in hand, to finish the work with co-counsel. The Oregon attorneys prepared the secret affidavits; I wrote the supplemental secret brief on my laptop. Three days later, we filed our documents with the district court.

The government attorneys were enraged. We'd caught them off guard. They wrote to Judge King and requested an immediate hearing, arguing we had prepared our secret papers and taken them to the courthouse without complying with CIA directives that require certain top secret documents to be "carried only in approved containers by authorized couriers" and "transmitted electronically only through 'specially designated and accredited communications circuits secured by an NSA-approved cryptographic system and/or protected distribution systems.'"

In fact, we'd only done what Judge King had said we could do. In a responding letter to the judge, we also pointed out that CIA directives don't apply to us because we aren't CIA employees. Nevertheless, in another moment of fear, we destroyed our drafts and notes for the secret filings. We no longer had copies of the secret documents we had filed.

During a short hearing, Judge King absolved us of wrongdoing but ordered that, in the future, we would have to confer with the DOJ attorneys before preparing secret filings. At the end of the hearing, the government attorneys demanded that we relinquish any electronic versions of the secret documents we had filed. The judge ordered all counsel to confer on this, too, and "see what you can work out." These two orders set the stage for some of the most bizarre experiences of my 29-year legal career.

Judge King suspended further proceedings on the standing issue until the pending 9th Circuit appeal was decided. That took nearly a year, during which time all of the four dozen cases nationwide challenging various aspects of the warrantless surveillance program were consolidated and transferred to the federal District Court in San Francisco for decision by a single judge, Vaughn Walker.

Meanwhile, the government attorneys demanded that we give them our computers to enable DOJ technicians to "wipe" the computers clean of any electronic remnants of secret material that might remain somewhere in the computers' hard drives. Because of attorney-client confidentiality considerations, we refused, proposing instead to do the wiping ourselves in whatever manner the government technicians suggested. We weren't about to let the DOJ go rummaging through our files. Negotiations on the "wiping" logistics dragged on throughout the winter.

Briefing blind

Come spring, we turned our attention to the 9th Circuit appeal, where the appellate court would decide whether the state secrets privilege required our lawsuit to be thrown out entirely. In June of 2007, the DOJ attorneys filed two opening briefs in the 9th Circuit. One brief was publicly available, to which we would be allowed to file a publicly available responsive brief. The other was filed in secret, under seal, for the judge's eyes only. The bad news for us was that we would not be permitted to see the government's secret brief; the (sort of) good news was that we could file our own secret brief in response.

Rebutting arguments you've not been allowed to see is a talent that isn't taught in law school. I consulted Kafka's "The Trial," looking for helpful tips, but found none. I tried guessing at what might be in the government's secret brief and then hazarding a response in our own. Because of Judge King's prior order, we had to confer with the DOJ attorneys on the logistics of how to do this secret filing.

The government attorneys referred us to DOJ employee Erin Hogarty, a Washington-based member of the DOJ's Litigation Security Section. I contacted Hogarty and said I needed to confer with her and review the documents we had filed under seal with Judge King the prior year. We made arrangements to meet at the federal courthouse in San Francisco on June 15, 2007.

Hogarty and I convened in a windowless interior room adjacent to Judge Walker's chambers. She had brought our previous secret filings with her. She set me up in the room with the filings, took my cellphone from me, instructed me that I could take no notes either then or later, and then left me alone while she sat outside the closed door. After a while, I called Hogarty back into the room and we discussed the logistics for drafting the secret appellate court filing.

Hogarty instructed me that the drafting session would take place in the DOJ's San Francisco offices under her supervision. I told her that, in addition to myself, I wanted another member of our Oregon legal team to attend the session. Before I even told her who I wanted, she volunteered "not Tom Nelson." A key member of the team, Nelson had helped prepare the affidavits we had filed the previous October and had hand-carried them to the courthouse. Hogarty said that Nelson had been "uncooperative," which I took to refer to strong objections he had voiced to the DOJ rummaging through his computer files. Hogarty then named one of our other Oregon team members -- Steven Goldberg -- as the only other attorney who could participate in the drafting session.

We chose a date: June 26, 2007. She then laid out ground rules: I could not prepare any advance notes that contained any classified information. I could not discuss any classified information over the telephone with Goldberg prior to the drafting session. Goldberg and I could only discuss the drafting "face to face" -- which was a problem, since I was in Oakland and he was in Portland. We would be put in a room at the DOJ's San Francisco offices, where we would be loaned a government computer on which to work.

The telltale banana peel

On the morning of June 26, Goldberg and I met Hogarty in the lobby of the San Francisco federal building. She took us through a locked door and into the DOJ offices, on a floor that was strangely deserted. She ushered us into a small interior room lined with bookshelves that had been completely emptied, except for a few chairs, a large table, a dusty telephone, a laptop computer and a printer. She took our cellphones.

At that point, we brought up the subject of Tom Nelson. Goldberg told Hogarty that we wanted to be able to telephone Nelson on a secure line during the drafting session, or, alternatively, have him fly down from Portland immediately to join us personally. Hogarty politely refused. Goldberg asked on whose instructions she was acting, and she named one of the DOJ attorneys, Andrew Tannenbaum -- although, as she put it, Tannenbaum had received the instructions from "higher up."

We went forward without Nelson, drafting our secret appellate brief in a DOJ office, on a DOJ computer, under the watch of a DOJ security officer -- that is, under the auspices and control of our adversary in the legal case. We could print out drafts but couldn't take them from the room; instead, we were to leave the drafts on the table to be shredded by Hogarty later. When the brief was done, we were to print out five copies: one for each of the three judges on the panel that would decide the appeal, one for the DOJ attorneys and one to be put in a special safe under Hogarty's supervision. She would personally give the judges their copies, which nobody else -- not the court clerks, not the judges' staff attorneys -- would be permitted to see. We would not be allowed to keep a copy of what we had written; the brief in Hogarty's safe was "our" copy.

Hogarty explained that anything we wrote down that contained classified information, then or later, would instantly become "derivatively classified" and thus unlawful for us to possess. I wondered whether this meant that the portion of my brain that remembers the Document is also "derivatively classified," making its presence in my skull unlawful.

Goldberg and I spent about three hours writing our response to the secret government brief we had not been allowed to see. I produced an initial draft without using notes. Goldberg edited and added to my draft, then I reedited, and so on. We took the brief through several drafts, printing out hard copies to work from as we went along. As lunchtime approached, I got hungry, which Goldberg mentioned to Hogarty during a bathroom break. Hogarty kindly offered me a banana. When we returned to our drafting, I ate the banana and set the peel alongside our stack of hard-copy drafts.

Finally, we printed out five copies of our finished brief, which I laid on the table alongside the stack of drafts and the banana peel, and I called for Hogarty. I told her: "Here's everything, even the banana peel." Hogarty said she would shred the drafts and the banana peel. (She may have been joking about the banana peel, but I couldn't be sure.) She returned our cellphones to us and escorted us out of the building into the San Francisco sunlight.

We submitted our 9th Circuit briefs on July 3, 2007. In the publicly available brief, we argued that the state secrets privilege shouldn't apply to the Al-Haramain case for several reasons. Among them was the Document's accidental disclosure to the plaintiffs, which meant the surveillance of them was no longer a secret. We also argued that we only want to use the Document to confirm the previously disclosed fact of the surveillance, and not to reveal any of its operational details, so the lawsuit did not threaten national security.

I can't reveal, of course, what we argued in our secret brief. The government subsequently filed a secret reply brief -- which we weren't allowed to see.

The court scheduled a hearing on the appeal for Aug. 15, 2007. At the same time, the court would hear oral arguments in a lawsuit filed by the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) against telecommunications carrier AT&T, challenging AT&T's wholesale disclosure of its customers' e-mail and telephone records to the government as part of the warrantless surveillance program.

The attack of the Samsonite Gorillas

On Aug. 8, 2007 -- more than nine months after I'd drafted the secret supplemental brief we'd filed with Judge King -- the DOJ people came to "wipe" my laptop clean of any electronic remnants of the brief. We'd finally agreed on the logistics: Erin Hogarty would bring a DOJ technician from Washington, D.C., and we'd meet in the windowless room adjacent to Judge Walker's chambers in San Francisco, where the technician would do the deed in my presence. It turned out to be more of a "whacking" than a "wiping."

Hogarty brought someone she introduced simply as "Miguel." By this time, alas, my laptop, which was old, was in its death throes. After Miguel tried logging onto the laptop and encountered fatal errors, he pronounced it dead. Hogarty asked me whether it would be OK if they physically destroyed the hard drive. I'd bought a new laptop and had managed to retrieve from the old one everything that I cared about, so I agreed.

They had brought no tools with them. Hogarty was about to canvass the building for a screwdriver, but I had a pending meeting elsewhere, so Miguel made do by fashioning a crude implement from the metal clip of his pen. He pried the back cover off the computer and removed the hard drive and memory board.

The situation grew darkly comic. They didn't have a hammer, so they started debating how to smash the hard drive. I suggested they smack it against the corner of the table that was in the room. That didn't do much. Hogarty then had an idea to put the thing on the floor and use a table leg on it. Miguel put down the hard drive, picked up the table and brought it down several times forcefully. The noise resounded, but the hard drive was impervious. One of the table legs became bent from the procedure.

Next, Miguel tried attacking the hard drive with his homemade tool. Soon he'd managed to pry off the hard drive cover and commenced scratching at the components. Meanwhile, Hogarty took the memory board and began banging on it on the floor with a chair leg. The memory board was weaker than the hard drive and cracked in several places. Then she held the memory board in her hands and tried bending it, but Miguel stopped her, warning that he'd seen someone get cut badly doing that -- evidently they'd done this sort of thing before.

I found myself thinking of the Samsonite Gorilla, the TV commercial from the 1970s in which a gorilla stomps on a piece of luggage that just won't break. I thought: "These people are entrusted with our national security?"

Eventually they managed to turn two shiny pieces of technology into about 20 jagged pieces of junk. Miguel started to throw the pieces into the wastebasket, but I asked if I could keep them -- a dark memento of sorts -- and he agreed.

As for my colleagues' computers, Hogarty and Miguel made a separate trip to Oregon, where they destroyed one of Portland attorney Zaha Hassan's Zip disks. They checked Goldberg's computer but apparently didn't find what they were looking for and left his hard drive intact. Nelson resisted all efforts to get at his electronic files, telling the DOJ attorneys that if they wanted access to his computer they would have to get a court order. They made no effort to do so.

Arguing gagged

A week later, I was arguing the case before a three-judge panel of the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco. Hogarty told me beforehand that if I said anything during the hearing that risked a public disclosure of classified information, she would stop the proceedings and clear the courtroom, suggesting I would likely suffer unspecified but unpleasant consequences.

In the middle of my argument, Judge Margaret McKeown asked me what information we needed from the Document to demonstrate our clients' standing to sue under FISA. I was at a loss. When Judge McKeown pressed me, I said: "I cannot tell you. I have a sealed filing in this case." When she pressed further, I said: "What's in the Document, I cannot mention it today." This was not my most eloquent moment as a lawyer.

Then, DOJ attorney Thomas Bondy stood at the lectern and delivered a mind-boggling rebuttal to our argument that the surveillance of our clients was no longer a secret.

"They don't know," Bondy said. "Let me make clear what I mean by that. When plaintiffs explain what they mean when they say they, in quotes, 'know,' they don't know. What they mean when they say that is that they -- although they think or believe or claim they were surveilled, it's possible they weren't surveilled ... When they say they know, what they mean by that, on their own terms, is that they don't know."

Bondy went on to argue "it is absolutely clear and undisputed that the world at large, the whole world, does not know whether or not any of the plaintiffs were surveilled." This incredible exchange ensued:

Judge McKeown: The world knows what they think they know, whatever that is that they know.

Bondy: Exactly. And that's less than actually knowing whether it's true.

Judge McKeown: Boy, we are really splitting the "knows."

At this point Judge Michael Hawkins interjected: "Sounds like Donald Rumsfeld."

Bondy: But your honor, let me be plain. If it's entirely possible, and I'm not saying one way or the other, obviously --

Judge McKeown: Right, because you don't yet know.

Bondy: It's entirely possible --

Judge McKeown: And we can't know.

Bondy: It's entirely possible that everything they think they know, just to give one example, is completely false. It's possible, or maybe it's partly true.

And so on. If I'd been permitted a reply, I would have quoted from Lewis Carroll -- not from "Alice's Adventures in Wonderland," but from his poem "Jabberwocky": "Beware the jubjub bird, and shun the frumious Bandersnatch!"

Endgame?

The 9th Circuit issued its ruling on Nov. 16, 2007, reversing Judge King's decision and sending the case back to Judge Walker for further proceedings. The appellate court ruled that if the state secrets privilege applies to the Al-Haramain lawsuit, it must be thrown out because the Document is indeed a state secret, regardless of its accidental disclosure to the plaintiffs, and because public disclosure of information concerning the Document would threaten national security. Judge King's compromise of allowing us to file affidavits describing the Document from memory was, the appellate court said, an improper "back door around the privilege." But the appellate court also ordered Judge Walker to decide whether FISA preempts the state secrets privilege in FISA litigation because of provisions in FISA for adjudicating claims under secure and confidential procedural conditions, which would allow our lawsuit to go forward.

Judge Walker's decision last week was a major victory for us. Walker concluded that FISA does indeed preempt the state secrets privilege. More broadly, he addressed the key issue raised by our lawsuit -- the validity of the "unitary executive" theory -- and said what we've been long awaiting: that the president does not have unbridled power to disregard federal statutory law in the name of national security. According to Judge Walker, "the authority to protect national security information is neither exclusive nor absolute in the executive branch. When Congress acts to contravene the president's authority, federal courts must give effect to what Congress has required."

But the ruling also sends us back down the rabbit hole once again. Judge Walker further held that, because of the peculiar way in which the applicable FISA provisions are written, we can't use the Document to confirm our clients' wiretapping until we first make some sort of preliminary showing -- using only non-classified information -- of "enough specifics" indicating that our clients were wiretapped. Only that could lead to a ruling giving us standing -- a burden Walker suggested might be "insurmountable." According to Walker, "if reports are to be believed," we will have "little difficulty" establishing standing once we are able to use the Document. But we can't use it yet. At this point, the Document alone just gives us what Walker called "actual but not useful notice" of our clients' unlawful surveillance. We need something more, from non-classified information, for that "actual" notice to become "useful."

In other words, we must show that our clients were surveilled before we can show that our clients were surveilled. The irony in this is not lost on Judge Walker, who commented that FISA is "not user-friendly."

Judge Walker gave us 30 days to restructure our complaint to make our preliminary case -- based on non-classified information -- for using the Document to confirm our clients' surveillance. We're grateful for the opportunity. We even think we can do it, using bits and pieces of non-classified information that has been revealed about the warrantless surveillance program and the terrorist designation of Al-Haramain in the 28 months since we commenced the lawsuit.

Meanwhile, Congress is on the verge of killing the pending lawsuits against the telecommunications carriers with a grant of retroactive immunity from liability. The 9th Circuit has not yet decided the AT&T case, evidently waiting to see whether Congress gives the carriers retroactive immunity. Other lawsuits against the government have been thrown out or are in danger of being thrown out for lack of standing -- since the plaintiffs in those cases have no proof that they were actual victims of the warrantless surveillance program. The Al-Haramain case is likely to become the last -- the only remaining hope for a determination of the legality of the president's extrajudical spying program and for Supreme Court review of the "unitary executive" theory.

It's hardly a secret that the Al-Haramain plaintiffs were spied upon -- it's been reported in Salon, the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times and the New Yorker magazine, among others. The reality is that the Al-Haramain case doesn't threaten national security; it threatens only the "unitary executive" theory and the notion that presidents can disregard an act of Congress at their pleasure. Yet we have had to litigate the Al-Haramain case in the shadow of secrecy, where the government wants the case to die quietly -- without a court ruling on whether the president of the United States has broken the law.

We, the members of the Al-Haramain legal team -- Ashlee Albies, Steven Goldberg, Bill Hancock, Zaha Hassan, Lisa Jaskol, Tom Nelson and I -- cannot let that happen without fighting to the end.

Shares