The news last week that the CIA had destroyed interrogation videotapes of two prisoners in its secret detention program had particular resonance at Guantánamo Bay, where I was attending a U.S. military tribunal hearing as a human rights observer. The destroyed tapes reportedly were evidence of the CIA’s brutal treatment, in secret prisons abroad, of two alleged high-level al-Qaida operatives, Abu Zubaydah and Abd al-Rahim al-Nahsiri. Both men are now in U.S. military custody in Guantánamo, together with 13 other former CIA prisoners the government refers to as “high-value detainees.”

Evidence from three of the other “high-value detainees” was a key issue in the hearing I attended, and showed how the Bush administration’s authorization of illegal detention and brutal prisoner treatment has tainted all aspects of its existing framework for handling key terrorist suspects. With the administration’s stubborn refusal to return to the rule of law, how can it be surprising that, in Washington, D.C., the CIA’s likely crimes have led to a coverup?

More light may be shed on the CIA’s destruction of evidence in the coming weeks, with congressional committees pursuing investigations. A test of new Attorney General Michael Mukasey’s leadership will be whether he appoints an investigator into the CIA’s wrongdoing who is independent of the Department of Justice. Not only has the DOJ been demoralized by scandal and accusations of partisanship, it was also responsible for writing legal memos that justified the CIA’s unlawful interrogation and detention program.

Just last month, the government told the American Civil Liberties Union that the DOJ had three memos, written in May 2005, that relate to CIA interrogation tactics. We know from news reports that at least two of these memos authorized the CIA to use harsh treatment, including waterboarding, freezing temperatures and head slaps, with the promise of impunity for interrogators. The disclosure was part of a court filing in ACLU v. Department of Defense, a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit, seeking the government’s release of the memos. A federal judge is expected to decide the issue early in 2008, but in the meantime, the CIA’s destruction of the interrogation tapes falls afoul of two existing court orders in the same case.

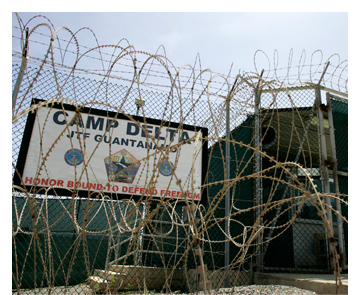

In Guantánamo, the destruction of CIA evidence loomed large as proceedings continued in the case of Salim Ahmed Hamdan, allegedly a driver and bodyguard for Osama bin Laden. At issue in Hamdan’s hearing was whether under the Military Commissions Act the government had the authority to try Hamdan as an “unlawful enemy combatant.” Congress passed the law in October 2006, under pressure from the Bush administration, on the eve of the midterm elections. The law circumvents due process safeguards that are a hallmark of American justice, in both the military’s own court-martial system and in the federal courts. For the more than 300 men held in Guantánamo for over six years, the Military Commissions Act stripped their right to challenge detention without charge through the ancient writ mechanism of habeas corpus. (The prisoners’ challenge to this provision was before the Supreme Court last Wednesday.)

The first thing that happened when I and the other three human rights observers went through security for Hamdan’s hearing was an apt metaphor for the rest of the two-day proceeding: We were forbidden from bringing the law into the courtroom. We could not bring in our copies of the Military Commissions Act, the rules of procedure, or even the military’s own charges against Hamdan. Apparently the military feared that such basic but essential documents posed some sort of security risk. We were each permitted to bring in only a notepad and a pen.

Hamdan’s hearing was the first time the government publicly presented evidence to support its “unlawful enemy combatant” charge, and the defense had the chance to refute the government’s case. The playing field was not level, however. For example, the defense wanted to call five Guantánamo prisoners, including three “high-value detainees,” Khalid Sheik Mohammed, Ramzi Bin al-Shib and Abu Faraj al-Libi, as witnesses. According to defense lawyers, these potential witnesses, and especially the “high-value detainees,” could refute the government’s charge that Hamdan had engaged in a conspiracy with senior members of al-Qaida to attack and murder civilians.

The judge permitted testimony from one of the detainees (and the defense and prosecution are negotiating the possible testimony of another), but refused to let the three “high-value detainees” testify, on the basis that the defense request was not timely in the proceedings. Government lawyers argued that the three were part of a highly classified special access program — a situation of the government’s own making, of course — and that only those with top secret clearance had access to them, which took time.

On the flight back from Guantánamo on Friday night, I asked Hamdan’s lead military defense lawyer, Lt. Brian Mizer, what it would take to get access. Lt. Mizer told me that, in fact, he had that top secret clearance and had been “read into” other special access programs on national security cases. It took about 20 minutes to get access, he said, but only if the government was willing. It has been widely reported that Muhammad, al-Shib, and al Libi have each been subjected to extreme cruelty, if not torture, in CIA custody. But the government takes the position that their treatment is classified and cannot be disclosed as a matter of the highest national security. But the credibility of that position has been destroyed along with the deliberate destruction of the CIA tapes.

Torture will also be an issue in any trial of any other “high-value detainees.” The government has said that it intends to try at least some of these men in military commission proceedings. But this is where Bush administration policies will come back to haunt us with a vengeance: Unlike the majority of Guantánamo detainees who appear to be low-level players or even innocent, Khalid Sheik Mohammed and others did likely engage in serious and heinous crimes. If so, they should be prosecuted and sentenced — but based on lawfully obtained evidence in full and fair proceedings that comport with the best traditions of American justice.

Instead, there’s no doubt that government torture and cruelty — and the question of what other evidence might exist or have been destroyed — will be an issue in their trials. Given the CIA’s destruction of the interrogations tapes, it will now be even harder to take government assurances of fair play and transparency at face value. There’s also the danger that information obtained through torture will be introduced in the military commissions, in violation of more than 200 years of American law and values. For the first time in U.S. history, and under pressure from the Bush administration, in the Military Commissions Act, Congress explicitly authorized an American tribunal to permit evidence obtained through “cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment” as long as it was obtained before Dec. 31, 2005. Even though the Military Commissions Act prohibits evidence obtained through torture, it could still come in because of this cruel treatment loophole, combined with the other provisions that permit secret evidence and evidence from second- and third-hand sources.

After 9/11, the Bush administration created a legal black hole in the name of national security — and six years later, we’re still trying to crawl out of it. The question now is, which direction will we take? At stake is nothing less than a return to the rule of law, the heart of American justice from which we have strayed so far.

The government could still choose to pull itself out of the morass it created by using two proven systems for detention and trial: either military courts-martials or the civilian criminal justice system.

Instead, it looks as if we’re on the verge of creating a different, but equally dubious approach. Over the summer, academics, policymakers and others have begun calling for another entirely new system: a national security court, with fewer procedural and substantive safeguards, to oversee the detention (possibly indefinitely, without criminal charge) and trial of terrorism suspects. Attorney General Mukasey indicated his willingness to consider such a system in a Wall Street Journal Op-Ed in August. And in June, Secretary of Defense Gates asked Congress to provide “a statutory basis for holding prisoners who should never be released and who may or may not be able to be put on trial.” We face the risk that, instead of repealing the Military Commissions Act, Congress could compound its mistake and enact a new, second-tier system of secondary justice.

Among other justifications, proponents argue that our existing military or civilian criminal justice systems are too protective of individual rights. They add that regular courts could give defendants access to sensitive national security information for their own defense, and that the threshold for evidence obtained from battlefields is too high. But none of these arguments addresses specifically why, if existing laws are inadequate, the better approach is not to identify flaws and amend them, rather than create a new system designed to circumvent core protections of constitutional due process.

The United States’ strength lies in its values, enshrined in the Constitution and the Bill of Rights, and in military and civilian criminal justice systems that reflect those values. It is because the Bush administration ignored and continues to ignore this that we are so far from having an effective and lawful arrangement for detaining and trying terrorism suspects.