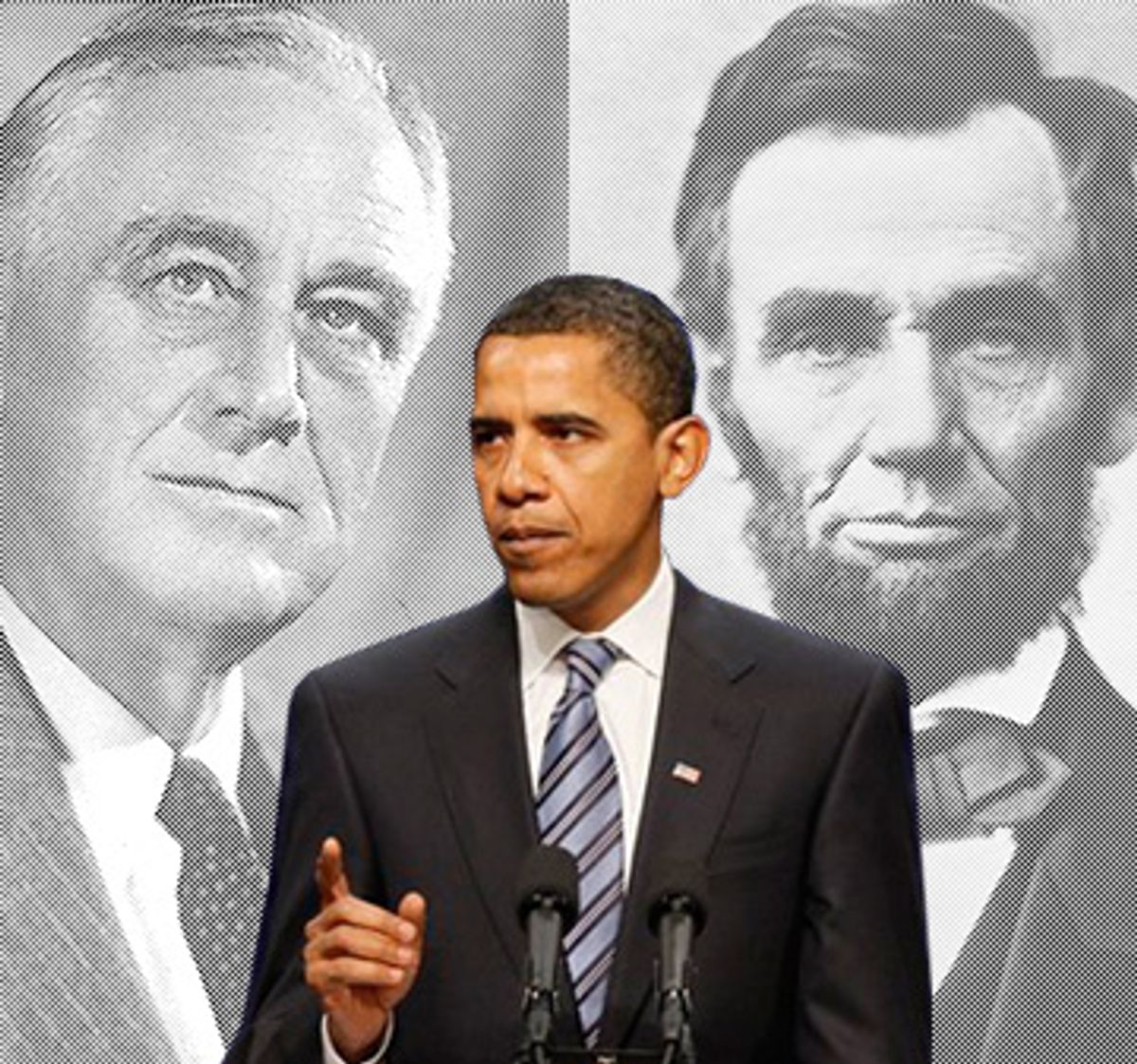

The inauguration of Barack Obama as president of the United States, along with the deepening of the Democratic majorities in both houses of Congress, marks more than a shift in the pendulum swings of partisan politics. In these pages I have suggested that it marks the dawn of a Fourth American Republic, in the way that the New Deal marked the beginning of Franklin Roosevelt's Third Republic of the United States and the Civil War and Reconstruction began Lincoln's Second Republic.

When Franklin Roosevelt was inaugurated, he had adopted the popular writer Stuart Chase's phrase "a New Deal," even though the contents of that New Deal were yet to be determined. In the absence of consensus on a similar term for the Age of Obama, we might draw on America's tradition of contractarian language -- the New Deal, the Fair Deal, the Square Deal, the New Covenant, the Contract With America -- and call this new period the era of the New Contract. That serves as well as any other name as a title for a synthesis of the three new strategies that the U.S. needs in the next generation: the Next American System, a new economic growth agenda; the Citizen-Based Social Contract, the completion of America's incomplete system of social insurance; and a New American Internationalism, based on a strategy of concert among the great powers. I don't expect the New Contract to be adopted as proposed. My purpose is to start a debate, not offer a prophecy.

In this, the first of three essays, I will explore the Next American System. The Next American System is the 21st century equivalent of Henry Clay's and Abraham Lincoln's American System, a program for modernizing the U.S. by promoting canals and railroads, steam-powered factories and national banking. It is also a version for our time of the program of the mid-20th century New Deal era for promoting economic recovery, exports, rural electrification, and highway construction.

Beginning in the 1970s, conservatives and centrist liberals shared the delusion that government was the problem and the self-regulating market the solution; neoliberal Democrats simply wanted more after-tax redistribution to compensate the market economy's losers. The economic crisis, which is resulting in the partial nationalization of the banking sector and industries like automobile production, should forever discredit this kind of Reagan-to-Rubin market utopianism. The alternative is not socialism or a mere revival of Keynesianism. It is a return to old-fashioned American-style developmental capitalism, which existed in both Lincoln Republican and Roosevelt Democrat forms. In developmental capitalism the government is viewed not as a neutral umpire between American producers and foreign producers, but as the coach of a mostly private team -- America Inc. Success in the game will make future debt-financed bailouts less likely and less necessary.

Beyond the stimulus, the priority of U.S. economic policy in the Obama years must be to avert future bubbles like the tech bubble and the housing bubble by addressing one of the root causes. That is the interaction between the chronic trade deficits of the U.S. and the chronic trade surpluses of China, Japan, Germany and the oil-exporting countries. The surplus U.S. dollars that those trade surplus nations have accumulated, invested in U.S. Treasury bills and other financial assets, made possible low U.S. interest rates, which in turn lowered the cost of borrowing to reckless speculators in tech stocks, mortgages and gold. Even a successful stimulus will merely return us to the world of chronic trade imbalances and the resulting bubbles and busts unless it is accompanied by a rebalancing of the world economy, in which the U.S. makes and exports more manufactured goods and the trade surplus nations export less and consume more. As Paul Krugman among others has argued, a "plausible route to sustained recovery would be a drastic reduction in the U.S. trade deficit, which soared at the same time the housing bubble was inflating. By selling more to other countries and spending more of our own income on U.S.-produced goods, we could get to full employment without a boom in either consumption or investment spending."

While pressuring the surplus nations to end unfair mercantilism and increase consumption, the U.S. must shift capital and labor from low-value-added industries like restaurants and retail to high-value-added manufacturing, high-value services, and research and development. Export-oriented, import-competing industries like automobiles and aerospace tend to have much higher productivity growth and R&D spending than other industries. Manufacturing-led growth for both the U.S. and global markets can melt away the debt legacy of today's economic emergency more rapidly.

In the new era of American developmental capitalism, the tax code will have two purposes -- raising adequate revenue and promoting "onshoring" or the growth of high-value-added production inside U.S. borders, by domestic and foreign companies alike. To encourage onshoring, the U.S. should lower or abolish its high corporate income tax, one of the few sound ideas of the American right. This would stimulate foreign direct investment in U.S. production. It would also reduce the incentive for U.S. companies to engage in tax avoidance schemes.

If the corporate income tax remains, then, as the economist Ralph Gomory has suggested, it should be made variable and lowered for high-value-added production inside the U.S. Alternately, the U.S. could replace the corporate income tax with a value-added tax (VAT). This would level the playing field for American companies. They are punished by de facto tariffs in the form of VATs in Europe and Asia, even as European and Asian exporters get government subsidies in the form of VAT rebates from their governments. In addition, a "Gomory VAT" could be reduced for high-value-added U.S. production, regardless of the nationality of the company or investors.

Adding a VAT to the mix of federal taxes would shift the U.S. toward the European mix of national consumption, payroll and income taxes. In the next half-century, even after runaway healthcare costs are controlled, the U.S. government share of GDP, while remaining relatively low by international standards, needs to expand by several percentage points to pay for universal healthcare, adequate retirement and a permanently higher level of infrastructure investment. Invisible taxes like payroll and consumption taxes are a better way to finance modern big government than highly visible taxes like income taxes and property taxes. Because they do not cause "sticker shock" to check writers around April 15 or when mortgage payments are due, they are harder for politicians to inveigh against on the campaign trail. Consumption and payroll taxes tend to be regressive in their effect on middle- and low-income people. But the exemption of necessities from consumption taxes, payroll tax rebates or (better yet) allowing biweekly credits against payroll tax withholding, an idea I have suggested elsewhere, can make these taxes more progressive.

To promote high-tech domestic manufacturing as the engine that will drive U.S. economic growth, America's energy policy must reduce greenhouse gas emissions in an industry-friendly way. This can be done by means of a federal oil and gas trigger-price system that provides stable energy prices for industry even as it supports alternate energy development. If the price of gas falls below a floor, gas taxes will increase, so that long-term investments in alternative energy sources will not be wiped out. If the price of gas rises above a ceiling, then a new U.S. civilian strategic petroleum reserve will flood the market to lower them.

Transportation is responsible for two-thirds of U.S. petroleum consumption. The answer is not to throw money at crash programs for this or that single technology -- ethanol, solar, wind. It is to build an intercontinental electric freight and passenger rail system to reduce reliance on trucks, cars and airplanes -- and a smart, green, national electric grid, open to a variety of clean energy sources, that can power the electric trains and, perhaps, in time, a hybrid or purely electric automobile fleet.

"Internal improvements" in the form of federally financed canals and railroads were part of the Clay-Lincoln American System. Long-overdue infrastructure investment must be part of the Next American System -- not only "shovel-ready projects" as part of the short-term stimulus, but a permanent commitment to green and high-tech energy, transportation and telecommunications grids. These are classic capital improvements that should be paid for by borrowing rather than upfront spending. President Obama supports a National Infrastructure Reinvestment Bank. Allowing such an infrastructure bank and similar federal economic development agencies to issue bonds, as state and local governments and agencies routinely do, would permit the federal government to channel private international capital and even money from foreign sovereign wealth funds into productivity-enhancing public investments, without selling or leasing U.S. infrastructure assets to foreign corporations or governments. (Except in emergencies like the present, ordinary government expenditures like defense and social insurance should be paid for out of current taxation, not financed by debt.)

Only a minority of Americans are likely to be employed directly in manufacturing. Even so, a new American developmental capitalism requires an active federal labor market policy that aims to shift labor out of low-productivity industries like retail and restaurants and into the goods-producing export sector and its supporting industries. If labor is to be diverted from wasteful low-productivity jobs into the traded-goods export sector, service sector wages need to be much higher. Congress should pass pro-union legislation, but at best it would take decades to rebuild the labor movement in the private sector. We don't have the time. The federal government should intervene directly, gradually raising the minimum wage until it is an inflation-adjusted living wage of $10 or more an hour.

Wouldn't a high minimum-wage policy destroy some jobs in the service sector? Let's hope so. Minimizing the number of menial jobs -- gradually, not all at once--is the whole point. There would, however, be no wave of outsourcing as a result of higher service sector wages, because most nontraded service sector jobs like nursing can be performed only in the U.S. One beneficial side effect of this policy would be an incentive to automate backward, labor-intensive sectors like hospitals and home construction. Another would be increased demand for U.S.-made goods by well-paid American workers. Higher wages need not lead to inflation as long as productivity growth increases -- in part as a result of the substitution of capital for more expensive labor

To further discourage employment in less-productive sectors, Congress should impose a federal servant tax on the employers of nannies, maids, gardeners, chauffeurs, restaurant and hotel workers and other menial servants in luxury industries. That labor could be more productively employed to the benefit of the nation in the export sector or non-luxury services like healthcare, elder care and education. We need more machinists and fewer maids. In a democratic republic, even affluent citizens should not be too good to take out the trash and mop the floor themselves. Middle-class and low-income Americans unable to afford necessary services like nursing could be given vouchers or tax credits, or those could be publicly provided.

The American growth agenda requires an immigration policy in the national interest. A policy of enhancing productivity growth by gradually raising wages in the service sector cannot succeed if unpatriotic employers can sabotage it. This means eliminating the ability of employers to pit illegal aliens or indentured servants like H-1B's against American citizens and legal immigrants. Most of today's illegal immigrants should be quickly made citizens with full rights -- but only after illegal immigration has been reduced to a trickle, by a national ID card system, severe employer sanctions and a combination of border fencing and enhanced border patrols. Meanwhile, indentured servitude in the U.S. should be outlawed by abolishing programs like the H-1B visa, which makes foreign workers dependent on their employers, and replacing it with a skills quota like those of the U.K. and Canada. Unlike H-1B's, qualified applicants would get green cards at once and compete on fair terms with American workers and legal permanent residents. Under no circumstances should the U.S. Chamber of Commerce be given its sinister "guest worker" program, which is really a colossal serf-worker program.

Most of these sensible immigration reforms were recommended in 1996 by President Clinton's Commission on Immigration Reform, headed by Barbara Jordan. President Obama and Congress should abandon the misguided Kennedy-McCain comprehensive immigration reform approach, with its dangerous concessions to the cheap-labor lobby, and move quickly to enact the decade-old recommendations of the Jordan Commission instead.

I'll conclude this discussion of a new growth agenda with the words of Barbara Jordan at the Democratic National Convention in 1992: "Why not change from a Party with a reputation of tax and spend to one with a reputation of investment and growth? ... A growth economy is a must. We can grow the economy and sustain an improved environment at the same time. When the economy is growing and we are taking care of our air and soil and water, we all prosper. And we can do all of that."

Shares