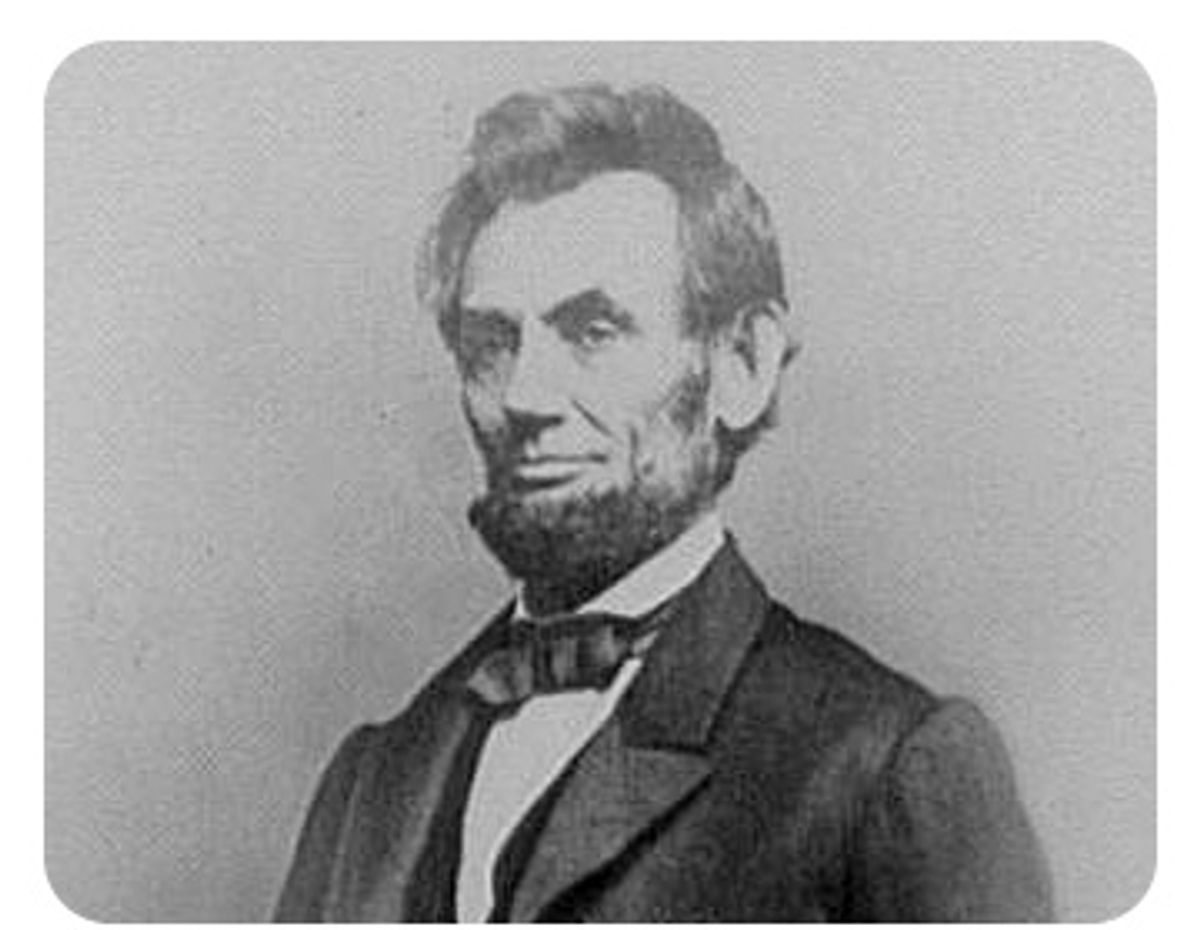

Today is the 200th anniversary of the birth of Abraham Lincoln on Feb. 12, 1809. President Barack Obama will celebrate it by speaking at a banquet in Lincoln's adopted hometown of Springfield, Ill. Obama has consciously and consistently sought to identify himself with his fellow Illinois politician, by launching his campaign in Springfield and taking a train, like Lincoln, to his inauguration.

Obama is not the only public figure who seeks to identify his cause with America's most iconic president. Ever since Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his "I Have a Dream" speech, the Lincoln Memorial has been part of the iconography of the civil rights movement. For its part, the Republican Party, whose first elected president was Abraham Lincoln, claims to be "Mr. Lincoln's party." Free-market conservatives like to quote Lincoln's speech in New Haven, Conn., on March 6, 1860, to make him sound like a Wall Street Journal libertarian: "I don't believe in a law to prevent a man from getting rich; it would do more harm than good." (Never mind that Lincoln said this to refute claims that his opposition to the ownership of slaves meant that Republicans wanted a "war on capital.") Conversely, liberals can dig out nuggets that seem to support the cause of labor, like these words from Lincoln's Annual Message to Congress in 1861: "Capital is only the fruit of labor, and could never have existed if labor had not first existed. Labor is the superior of capital." (Never mind that this is a reference to Locke's labor theory of value, not to collective bargaining). Log Cabin Republicans claim that because Lincoln supported black rights he would have supported gay rights, while Straussian conservatives claim that because he supported black rights he would support a federal ban on abortion.

Others understandably seek to turn the Lincoln bicentennial into a festival of nonpartisan national unity. According to many popular historians, we need only remember that Lincoln saved the Union and destroyed slavery. You can't get more bipartisan than that. In 2009, how many Americans defend secession and slavery?

So are we all Lincolnians now? Maybe not. It's perfectly reasonable to ask what political movements and factions today would attract someone with Lincoln's political values. Lincoln was not King Arthur, living in a wholly alien society. Many of the issues of the mid-19th century -- from the role of the federal government in the economy to whether America is a Christian nation to evolution vs. creationism -- remain issues in the early 21st century.

In his long career as a Whig and Republican politician, Abraham Lincoln expressed views on many subjects other than unionism and slavery. Americans are rightly curious about the beliefs and values of the most iconic American president. Contemporary historians are inclined to deflect such questions by mumbling that Lincoln was "mysterious" or "puzzling." But there is no lack of evidence. Lincoln's ideas about race, religion, economics and the Constitution are well known to scholars. What Lincoln might think about today's American politics is not only a legitimate question, but one that can be answered with a reasonable chance of success.

Let's begin with race and immigration. Lincoln was not a radical abolitionist committed like all but a few modern Americans to a colorblind society. If he had been, he would have been a marginal figure in national politics. Like most Republicans who were not radicals, Lincoln wanted to keep slavery out of the Midwest and the North in the interests of white farmers and workers. At the same time, Lincoln sincerely believed that slavery was utterly incompatible with the natural rights liberalism on which the U.S. was founded. He passionately and eloquently denounced efforts to "dehumanize the negro -- to take away from him the right of ever striving to be a man ..." A "colonizationist" like his hero Henry Clay, as well as James Madison and Thomas Jefferson, Lincoln initially favored a gradual end to slavery, followed by the federally financed, voluntary emigration of freed blacks to Africa, Central America or the Caribbean. During the Civil War, however, Lincoln abandoned his support for colonization, and shortly before his death, in words that reflect his prejudices, he was recommending that states consider granting the right to vote to "intelligent" blacks and black Union veterans. More important, Lincoln firmly defended the principle of natural equality that was invoked as the basis for the much later Civil Rights Revolution. Unlike the states' rights conservatives of his day and ours, the author of the Emancipation Proclamation did not have philosophical objections to federal enforcement of civil rights.

What about immigration? While Lincoln did not question the white-only immigration policy of his time, he did reject the anti-Catholic, anti-European nativism of many of his fellow Whigs: "I am not a Know-Nothing," he wrote his former law partner Joshua Speed in 1855. "As a nation, we began by declaring that 'all men are created equal.' We now practically read it 'all men are created equal, except negroes.' When the Know-Nothings get control, it will read 'all men are created equal, except negroes, and foreigners, and catholics.'" Someone with Lincoln's basic values might be concerned that ill-devised immigration policies could reduce wages for some citizens; that, after all, was one of the arguments of the Lincoln Republicans against the expansion of slavery. But Lincoln's dismissal of prejudice against Irish and German Catholics naturally leads to dismissal of all arguments about immigration based in bigotry.

What about economics? In his first campaign manifesto of 1832, the young Whig Party politician declared: "My politics are short and sweet, like the old woman's dance. I am in favor of a national bank ... in favor of the internal improvements system and a high protective tariff." In short, Lincoln was in favor of a strong federal government that actively promoted American infrastructure and manufacturing.

Would a modern Lincoln denounce infrastructure spending projects as boondoggles? Unlikely. As an Illinois legislator, Lincoln promoted an ambitious infrastructure scheme that bankrupted the state. Undeterred, Lincoln led the federal government to lavish subsidies on the railroads, which as a result nearly doubled American track miles between 1860 and 1870.

Would a contemporary American sharing the values of Lincoln oppose "Buy American" provisions in the stimulus package? Lincoln was a lifelong economic nationalist who favored federal government support for American industry against foreign competition. In 1859, shortly before becoming president, Lincoln wrote: "I was an old Henry Clay-Tariff-Whig. In old times I made more speeches on that subject [the need for protectionist tariffs] than any other. I have not since changed my views." Thanks to Lincoln and his congressional allies, the average U.S. tariff on dutiable imports ranged between 40 and 50 percent. The U.S. policy of import substitution, in defiance of free trade theory, helped to make the U.S. the world's greatest industrial powerhouse in the world in the generation following Lincoln's death. (Having made effective use of protectionism to become the dominant manufacturing power, the U.S. eventually changed its tune and began promoting free trade to gain export markets.)

Would Lincoln join the fiscal conservatives who fret over the size of the national debt? Largely because of the Civil War, the federal budget grew from $63 million in 1860 to $1.2 billion in 1865. Following his assassination, his widow, Mary, explained that Lincoln had wanted to take a trip to Europe, after leaving office: "After his return from Europe, he intended to cross the Rocky Mountains and go to California, where the soldiers were to be digging out gold to pay the national debt." I don't think that today's deficit hawks would be amused by Lincoln's joke.

Would Lincoln join today's Republicans in calling for more tax cuts as the answer to every problem? President Lincoln signed the bills creating the IRS and the first U.S. income tax.

What would Abraham Lincoln think of the religious right in today's Republican Party -- and more to the point, what would the religious right think of him? According to his law partner William Herndon, in 1834 Lincoln wrote "a little book on infidelity" in which he questioned "the divinity of Christ -- Special Inspiration -- Revelation &c." He reluctantly burned it, when his friends warned him it would damage his career. During the same year, the young Whig politician criticized supporters of the Democrat Peter Cartwright, an evangelist turned politician like Mike Huckabee, as "in some degree priest-ridden." When he ran for Congress in 1846, Lincoln was accused by the religious right of the day of being an infidel; his reply was a classic of politically motivated equivocation: "That I am not a member of any Christian Church is true; but I have never denied the truth of the Scriptures; and I have never spoken with intentional disrespect of religion in general, or any denomination of Christians in particular."

Lincoln's speeches were deeply influenced by the King James Bible, and as the costs of the Civil War mounted he dwelled on the mysteries of Providence. According to his closest associates, however, he never became a Christian. "He had no faith in the Christian sense of the term -- had faith in laws, principles, effects and causes," observed David Davis, a longtime friend whom Lincoln appointed to the Supreme Court. His law partner John Todd Stewart wrote: "He was an avowed and open infidel and sometimes bordered on atheism ... went further against Christian beliefs and doctrines and principles than any man I ever heard; he shocked me ... Lincoln always denied that Jesus was the Christ of God -- denied that Jesus was the son of God as understood and maintained by the Christian Church."

While Lincoln did not believe that Jesus was the son of God, he did believe in biological evolution. His law partner Herndon recalled that Lincoln took great interest in "Vestiges of Creation" (1844) by Robert Chambers, a book that popularized the idea of evolution even before Darwin published his theory of natural selection as its mechanism: "The treatise interested him greatly, and he was deeply impressed with the notion of the so-called 'universal law' -- evolution; he did not extend greatly his researches, but by continued thinking in a single channel seemed to grow into a warm advocate of the new doctrine."

Can anyone believe that a contemporary Republican politician who refused to join a Christian church, who was described by friends as "an avowed and open infidel," who had written a book mocking the miracles in the Bible, who described evangelical voters as "priest-ridden," and was a "warm advocate" of evolutionary theory, could be nominated for president by today's Republican Party?

There is one subject, to be sure, on which the contemporary right might approve of Lincoln. On the basis of claims of executive power, during the Civil War Lincoln ordered the eventual nationwide suspension of habeas corpus, a policy ratified by Congress. He ordered the arrest of legislators in Maryland and the deportation to the Confederacy of an Ohio Democrat who criticized him. Even Lincoln's allies like Supreme Court Justice David Davis thought that Lincoln went too far in the emergency, but Lincoln wrote: "I think the time not unlikely to come when I shall be blamed for having made too few arrests rather than too many." Here, if nowhere else, the conservative Republicans who have defended the Bush administration's authorization of torture and denounced the closing of Guantánamo might finally find an aspect of Lincoln to admire.

None of this means that someone with Abraham Lincoln's views today would be found on the left. Lincoln the wealthy railroad lawyer was too enthusiastic about business, industrial growth and the conversion of wilderness into cities for the approval of those contemporary progressives who despise capitalism and denounce sprawl. A contemporary Lincoln might find himself more at home among Democrats focused on technology and economic growth.

One thing, however, is clear: Nobody with Lincoln's religious and political beliefs could be a conservative Republican on the bicentennial of Lincoln's birthday. Until a generation ago, someone who thought the way Lincoln did could still find a home among the moderate Republicans of the Northeast and Midwest. But today Lincoln Republicans have been driven out of the Republican Party by an alliance of the religious right and free-market fundamentalists. The Northern and Midwestern states that voted for Lincoln in 1860 are largely Democratic today. Take away the thinly populated mountain-prairie West, and the Republican Party is essentially the party of the former Confederacy. Lincoln, the first Republican president, would find himself marginalized in the party he helped to found, by the political descendants of the Southern Jeffersonians and Jacksonians whom he opposed throughout his political career and defeated in war. While today's Democrats are not necessarily the party of Lincoln, the GOP definitely is not Mr. Lincoln's party anymore.

Lincoln concluded his First Inaugural Address on March 4, 1861, by declaring: "I am loath to close. We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battle-field, and patriot grave, to every living heart and hearth-stone, all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely as they will be, by the better angels of our nature." Lincoln's hope in his first inaugural for reconciliation and his call in his second inaugural in 1865 for reunion "[w]ith malice toward none; with charity for all" were separated by the volcanic chasm of the Civil War. For Lincoln, compromise was desirable, but never at the expense of principle. In today's national emergency, the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression, conflict is preferable to compromise between justice and injustice or sanity and error. Winners should be charitable -- but first they have to win. In the words of Abraham Lincoln in his Cooper Union Address in 1860: "Let us have faith that right makes might, and in that faith, let us, to the end, dare to do our duty as we understand it."

Shares