If, like me, you've been following America's torture policies not just for the last few years but for decades, you can't help but experience that eerie feeling of déjà vu these days. With the departure of George W. Bush and Dick Cheney from Washington and the arrival of Barack Obama, it may just be back to the future when it comes to torture policy, a turn away from a dark, do-it-yourself ethos and a return to the outsourcing of torture that went on, with the support of both Democrats and Republicans, in the Cold War years.

Like Chile after the regime of General Augusto Pinochet or the Philippines after the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos, Washington after Bush is now trapped in the painful politics of impunity. Unlike anything our allies have experienced, however, for Washington, and so for the rest of us, this may prove a political crisis without end or exit.

Despite dozens of official inquiries in the five years since the Abu Ghraib photos first exposed our abuse of Iraqi detainees, the torture scandal continues to spread like a virus, infecting all who touch it, including now Obama himself. By embracing a specific methodology of torture, covertly developed by the CIA over decades using countless millions of taxpayer dollars and graphically revealed in those Iraqi prison photos, we have condemned ourselves to retreat from whatever promises might be made to end this sort of abuse and are instead already returning to a bipartisan consensus that made torture America's secret weapon throughout the Cold War.

Despite the 24 version of events, the Bush administration did not simply authorize traditional, bare-knuckle torture. What it did do was develop to new heights the world's most advanced form of psychological torture, while quickly recognizing the legal dangers in doing so. Even in the desperate days right after 9/11, the White House and Justice Department lawyers who presided over the Bush administration's new torture program were remarkably punctilious about cloaking their decisions in legalisms designed to preempt later prosecution.

To most Americans, whether they supported the Bush administration torture policy or opposed it, all of this seemed shocking and very new. Not so, unfortunately. Concealed from Congress and the public, the CIA had spent the previous half-century developing and propagating a sophisticated form of psychological torture meant to defy investigation, prosecution, or prohibition -- and so far it has proved remarkably successful on all these counts. Even now, since many of the leading psychologists who worked to advance the CIA's torture skills have remained silent, we understand surprisingly little about the psychopathology of the program of mental torture that the Bush administration applied so globally.

Physical torture is a relatively straightforward matter of sadism that leaves behind broken bodies, useless information and clear evidence for prosecution. Psychological torture, on the other hand, is a mind maze that can destroy its victims, even while entrapping its perpetrators in an illusory, almost erotic, sense of empowerment. When applied skillfully, it leaves few scars for investigators who might restrain this seductive impulse. However, despite all the myths of these last years, psychological torture, like its physical counterpart, has proven an ineffective, even counterproductive, method for extracting useful information from prisoners.

Where it has had a powerful effect is on those ordering and delivering it. With their egos inflated beyond imagining by a sense of being masters of life and death, pain and pleasure, its perpetrators, when in office, became forceful proponents of abuse, striding across the political landscape like Nietzschean supermen. After their fall from power, they have continued to maneuver with extraordinary determination to escape the legal consequences of their actions.

Before we head deeper into the hidden history of the CIA's psychological torture program, however, we need to rid ourselves of the idea that this sort of torture is somehow "torture lite" or merely, as the Bush administration renamed it, "enhanced interrogation." Although seemingly less brutal than physical methods, psychological torture actually inflicts a crippling trauma on its victims. "Ill treatment during captivity, such as psychological manipulations and forced stress positions," Dr. Metin Basoglu has reported in the Archives of General Psychiatry after interviewing 279 Bosnian victims of such methods, "does not seem to be substantially different from physical torture in terms of the severity of mental suffering."

A secret history of psychological torture

The roots of our present paralysis over what to do about detainee abuse lie in the hidden history of the CIA's program of psychological torture. Early in the Cold War, panicked that the Soviets had somehow cracked the code of human consciousness, the Agency mounted a "Special Interrogation Program" whose working hypothesis was: "Medical science, particularly psychiatry and psychotherapy, has developed various techniques by means of which some external control can be imposed on the mind/or will of an individual, such as drugs, hypnosis, electric shock and neurosurgery."

All of these methods were tested by the CIA in the 1950s and 1960s. None proved successful for breaking potential enemies or obtaining reliable information. Beyond these ultimately unsuccessful methods, however, the Agency also explored a behavioral approach to cracking that "code." In 1951, in collaboration with British and Canadian defense scientists, the Agency encouraged academic research into "methods concerned in psychological coercion." Within months, the Agency had defined the aims of its top-secret program, code-named Project Artichoke, as the "development of any method by which we can get information from a person against his will and without his knowledge."

This secret research produced two discoveries central to the CIA's more recent psychological paradigm. In classified experiments, famed Canadian psychologist Donald Hebb found that he could induce a state akin to drug-induced hallucinations and psychosis in just 48 hours -- without drugs, hypnosis or electric shock. Instead, for two days student volunteers at McGill University simply sat in a comfortable cubicle deprived of sensory stimulation by goggles, gloves and earmuffs. "It scared the hell out of us," Hebb said later, "to see how completely dependent the mind is on a close connection with the ordinary sensory environment, and how disorganizing to be cut off from that support."

During the 1950s, two neurologists at Cornell Medical Center, under CIA contract, found that the most devastating torture technique of the Soviet secret police, the KGB, was simply to force a victim to stand for days while the legs swelled, the skin erupted in suppurating lesions, and hallucinations began -- a procedure which we now politely refer to as "stress positions."

Four years into this project, there was a sudden upsurge of interest in using mind control techniques defensively after American prisoners in North Korea suffered what was then called "brainwashing." In August 1955, President Eisenhower ordered that any soldier at risk of capture should be given "specific training and instruction designed to ... withstand all enemy efforts against him."

Consequently, the Air Force developed a program it dubbed SERE (Survival, Evasion, Resistance, Escape) to train pilots in resisting psychological torture. In other words, two intertwined strands of research into torture methods were being explored and developed: aggressive methods for breaking enemy agents and defensive methods for training Americans to resist enemy inquisitors.

In 1963, the CIA distilled its decade of research into the curiously named KUBARK Counter-intelligence Interrogation manual, which stated definitively that sensory deprivation was effective because it made "the regressed subject view the interrogator as a father-figure ... strengthening ... the subject's tendencies toward compliance." Refined through years of practice on actual human beings, the CIA's psychological paradigm now relies on a mix of sensory overload and deprivation via seemingly banal procedures: the extreme application of heat and cold, light and dark, noise and silence, feast and famine -- all meant to attack six essential sensory pathways into the human mind.

After codifying its new interrogation methods in the KUBARK manual, the Agency spent the next 30 years promoting these torture techniques within the U.S. intelligence community and among anti-communist allies. In its clandestine journey across continents and decades, the CIA's psychological torture paradigm would prove elusive, adaptable, devastatingly destructive, and powerfully seductive. So darkly seductive is torture's appeal that these seemingly scientific methods, even when intended for a few Soviet spies or al-Qaida terrorists, soon spread uncontrollably in two directions -- toward the torture of the many and into a paroxysm of brutality toward specific individuals. During the Vietnam War, when the CIA applied these techniques in its search for information on top Vietcong cadre, the interrogation effort soon degenerated into the crude physical brutality of the Phoenix Program, producing 46,000 extrajudicial executions and little actionable intelligence.

In 1994, with the Cold War over, Washington ratified the U.N. Convention Against Torture, seemingly resolving the tension between its anti-torture principles and its torture practices. Yet when President Clinton sent this Convention to Congress, he included four little-noticed diplomatic "reservations" drafted six years before by the Reagan administration and focused on just one word in those 26 printed pages: "mental."

These reservations narrowed (just for the United States) the definition of "mental" torture to include four acts: the infliction of physical pain, the use of drugs, death threats or threats to harm another. Excluded were methods such as sensory deprivation and self-inflicted pain, the very techniques the CIA had propagated for the past 40 years. This definition was reproduced verbatim in Section 2340 of the U.S. Federal Code and later in the War Crimes Act of 1996. Through this legal legerdemain, Washington managed to agree, via the U.N. Convention, to ban physical abuse even while exempting the CIA from the U.N.'s prohibition on psychological torture.

This little noticed exemption was left buried in those documents like a landmine and would detonate with phenomenal force just 10 years later at Abu Ghraib prison.

War on terror, war of torture

Right after his public address to a shaken nation on Sept. 11, 2001, President Bush gave his staff secret orders to pursue torture policies, adding emphatically, "I don't care what the international lawyers say, we are going to kick some ass." In a dramatic break with past policy, the White House would even allow the CIA to operate its own global network of prisons, as well as charter air fleet to transport seized suspects and "render" them for endless detention in a supranational gulag of secret "black sites" from Thailand to Poland.

The Bush administration also officially allowed the CIA ten "enhanced" interrogation methods designed by agency psychologists, including "waterboarding." This use of cold water to block breathing triggers the "mammalian diving reflex," hardwired into every human brain, thus inducing an uncontrollable terror of impending death.

As Jane Mayer reported in the New Yorker, psychologists working for both the Pentagon and the CIA "reverse engineered" the military's SERE training, which included a brief exposure to waterboarding, and flipped these defensive methods for use offensively on al-Qaida captives. "They sought to render the detainees vulnerable -- to break down all of their senses," one official told Mayer. "It takes a psychologist trained in this to understand these rupturing experiences." Inside Agency headquarters, there was, moreover, a "high level of anxiety" about the possibility of future prosecutions for methods officials knew to be internationally defined as torture. The presence of Ph.D. psychologists was considered one "way for CIA officials to skirt measures such as the Convention Against Torture."

From recently released Justice Department memos, we now know that the CIA refined its psychological paradigm significantly under Bush. As described in the classified 2004 Background Paper on the CIA's Combined Use of Interrogation Techniques, each detainee was transported to an Agency black site while "deprived of sight and sound through the use of blindfolds, earmuffs, and hoods." Once inside the prison, he was reduced to "a baseline, dependent state" through conditioning by "nudity, sleep deprivation (with shackling ...), and dietary manipulation."

For "more physical and psychological stress," CIA interrogators used coercive measures such as "an insult slap or abdominal slap" and then "walling," slamming the detainee's head against a cell wall. If these failed to produce the results sought, interrogators escalated to waterboarding, as was done to Abu Zubaydah "at least 83 times during August 2002" and Khalid Sheikh Mohammad 183 times in March 2003 -- so many times, in fact, that the repetitiousness of the act can only be considered convincing testimony to the seductive sadism of CIA-style torture.

In a parallel effort launched by Bush-appointed civilians in the Pentagon, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld gave General Geoffrey Miller command of the new American military prison at Guantánamo in late 2002 with ample authority to transform it into an ad hoc psychology lab. Behavioral Science Consultation Teams of military psychologists probed detainees for individual phobias like fear of the dark. Interrogators stiffened the psychological assault by exploiting what they saw as Arab cultural sensitivities when it came to sex and dogs. Via a three-phase attack on the senses, on culture and on the individual psyche, interrogators at Guantánamo perfected the CIA's psychological paradigm.

After General Miller visited Iraq in September 2003, the U.S. commander there, General Ricardo Sanchez, ordered Guantánamo-style abuse at Abu Ghraib prison. My own review of the 1,600 still-classified photos taken by American guards at Abu Ghraib -- which journalists covering this story seem to share like Napster downloads -- reveals not random, idiosyncratic acts by "bad apples," but the repeated, constant use of just three psychological techniques: hooding for sensory deprivation, shackling for self-inflicted pain and (to exploit Arab cultural sensitivities) both nudity and dogs. It is no accident that Private Lynndie England was famously photographed leading an Iraqi detainee leashed like a dog.

These techniques, according to the New York Times, then escalated virally at five Special Operations field interrogation centers where detainees were subjected to extreme sensory deprivation, beating, burning, electric shock and waterboarding. Among the thousand soldiers in these units, 34 were later convicted of abuse and many more escaped prosecution only because records were officially "lost."

"Behind the green door" at the White House

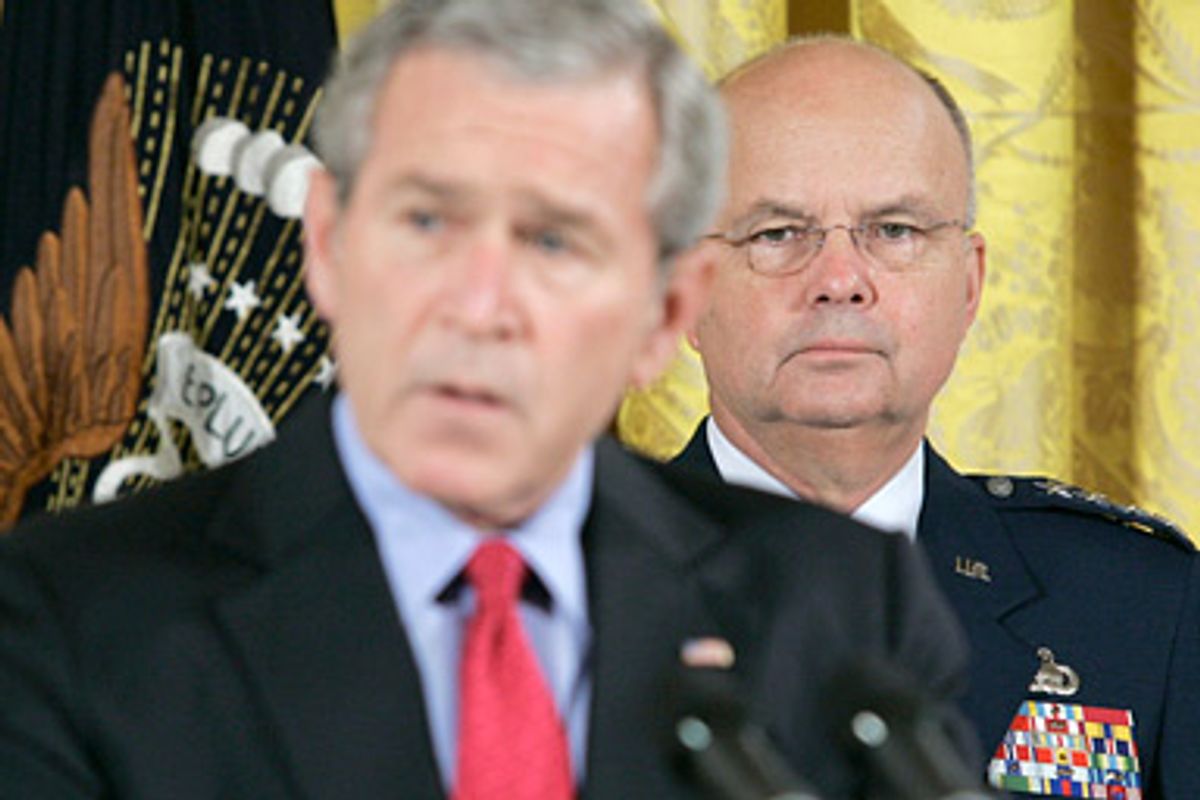

Further up the chain of command, National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice, as she recently told the Senate, "convened a series of meetings of NSC [National Security Council] principals in 2002 and 2003 to discuss various issues … relating to detainees." This group, including Vice President Cheney, Attorney General John Ashcroft, Secretary of State Colin Powell and CIA director George Tenet, met dozens of times inside the White House Situation Room.

After watching CIA operatives mime what Rice called "certain physical and psychological interrogation techniques," these leaders, their imaginations stimulated by graphic visions of human suffering, repeatedly authorized extreme psychological techniques stiffened by hitting, walling and waterboarding. According to an April 2008 ABC News report, Attorney General Ashcroft once interrupted this collective fantasy by asking aloud, "Why are we talking about this in the White House? History will not judge this kindly."

In mid-2004, even after the Abu Ghraib photos were released, these principals met to approve the use of CIA torture techniques on still more detainees. Despite mounting concerns about the damage torture was doing to America's standing, shared by Colin Powell, Condoleezza Rice commanded Agency officials with the cool demeanor of a dominatrix. "This is your baby," she reportedly said. "Go do it."

Cleansing torture

Even as they exercise extraordinary power over others, perpetrators of torture around the world are assiduous in trying to cover their tracks. They construct recondite legal justifications, destroy records of actual torture and paper the files with spurious claims of success. Hence, the CIA destroyed 92 interrogation videotapes, while Vice President Cheney now berates Obama incessantly (five times in his latest Fox News interview) to declassify "two reports" which he claims will show the informational gains that torture offered -- possibly because his staff salted the files at the NSC or the CIA with documents prepared for this very purpose.

Not only were Justice Department lawyers aggressive in their advocacy of torture in the Bush years, they were meticulous from the start, in laying the legal groundwork for later impunity. In three torture memos from May 2005 that the Obama administration recently released, Bush's Deputy Assistant Attorney General Stephen Bradbury repeatedly cited those original U.S. diplomatic "reservations" to the U.N. Convention Against Torture, replicated in Section 2340 of the Federal code, to argue that waterboarding was perfectly legal since the "technique is not physically painful." Anyway, he added, careful lawyering at Justice and the CIA had punched loopholes in both the U.N. Convention and U.S. law so wide that these Agency techniques were "unlikely to be subject to judicial inquiry."

Just to be safe, when Vice President Cheney presided over the drafting of the Military Commissions Act of 2006, he included clauses, buried in 38 pages of dense print, defining "serious physical pain" as the "significant loss or impairment of the function of a bodily member, organ, or mental faculty." This was a striking paraphrase of the outrageous definition of physical torture as pain "equivalent in intensity to ... organ failure, impairment of bodily function, or even death" in John Yoo's infamous August 2002 "torture memo," already repudiated by the Justice Department.

Above all, the Military Commissions Act protected the CIA's use of psychological torture by repeating verbatim the exculpatory language found in those Clinton-era, Reagan-created reservations to the U.N. Convention and still embedded in Section 2340 of the Federal code. To make doubly sure, the act also made these definitions retroactive to November 1997, giving CIA interrogators immunity from any misdeeds under the Expanded War Crimes Act of 1997 which punishes serious violations with life imprisonment or death.

No matter how twisted the process, impunity -- whether in England, Indonesia or America -- usually passes through three stages:

1. Blame the supposed "bad apples."

2. Invoke the security argument. ("It protected us.")

3. Appeal to national unity. ("We need to move forward together.")

For a year after the Abu Ghraib exposé, Rumsfeld's Pentagon blamed various low-ranking bad apples by claiming the abuse was "perpetrated by a small number of U.S. military." In his statement on May 13, while refusing to release more torture photos, President Obama echoed Rumsfeld, claiming the abuse in these latest images, too, "was carried out in the past by a small number of individuals."

In recent weeks, Republicans have taken us deep into the second stage with Cheney's statements that the CIA's methods "prevented the violent deaths of thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands, of people."

Then, on April 16, President Obama brought us to the final stage when he released the four Bush-era memos detailing CIA torture, insisting: "Nothing will be gained by spending our time and energy laying blame for the past." During a visit to CIA headquarters four days later, Obama promised that there would be no prosecutions of Agency employees. "We've made some mistakes," he admitted, but urged Americans simply to "acknowledge them and then move forward." The president's statements were in such blatant defiance of international law that the U.N.'s chief official on torture, Manfred Nowak, reminded him that Washington was actually obliged to investigate possible violations of the Convention Against Torture.

This process of impunity is leading Washington back to a global torture policy that, during the Cold War, was bipartisan in nature: publicly advocating human rights while covertly outsourcing torture to allied governments and their intelligence agencies. In retrospect, it may become ever more apparent that the real aberration of the Bush years lay not in torture policies per se, but in the president's order that the CIA should operate its own torture prisons. The advantage of the bipartisan torture consensus of the Cold War era was, of course, that it did a remarkably good job most of the time of insulating Washington from the taint of torture, which was sometimes remarkably widely practiced.

There are already some clear signs of a policy shift in this direction in the Obama era. Since mid-2008, U.S. intelligence has captured a half-dozen al-Qaida suspects and, instead of shipping them to Guantánamo or to CIA secret prisons, has had them interrogated by allied Middle Eastern intelligence agencies. Showing that this policy is again bipartisan, Obama's new CIA director Leon Panetta announced that the Agency would continue to engage in the rendition of terror suspects to allies like Libya, Pakistan or Saudi Arabia where we can, as he put it, "rely on diplomatic assurances of good treatment." Showing the quality of such treatment, Time magazine reported on May 24 that Ibn al-Sheikh al-Libi, who famously confessed under torture that Saddam Hussein had provided al-Qaida with chemical weapons and later admitted his lie to Senate investigators, had committed "suicide" in a Libyan cell.

The price of impunity

This time around, however, a long-distance torture policy may not provide the same insulation as in the past for Washington. Any retreat into torture by remote control is, in fact, only likely to produce the next scandal that will do yet more damage to America's international standing.

Over a 40-year period, Americans have found themselves mired in this same moral quagmire on six separate occasions: following exposés of CIA-sponsored torture in South Vietnam (1970), Brazil (1974), Iran (1978), Honduras (1988) and then throughout Latin America (1997). After each exposé, the public's shock soon faded, allowing the Agency to resume its dirty work in the shadows.

Unless some formal inquiry is convened to look into a sordid history that reached its depths in the Bush era, and so begins to break this cycle of deceit, exposé and paralysis followed by more of the same, we're likely, a few years hence, to find ourselves right back where we are now. We'll be confronted with the next American torture scandal from some future iconic dungeon, part of a dismal, ever lengthening procession that has led from the tiger cages of South Vietnam through the Shah of Iran's prison cells in Tehran to Abu Ghraib and the prison at Bagram Air Base in Afghanistan.

The next time, however, the world will not have forgotten those photos from Abu Ghraib. The next time, the damage to this country will be nothing short of devastating.

Shares