"We had to struggle with the old enemies of peace: business and financial monopoly, speculation, reckless banking, class antagonism, sectionalism, war profiteering," President Franklin Roosevelt told an audience in Madison Square Garden in 1936. "They had begun to consider the Government of the United States as a mere appendage to their own affairs. We know now that Government by organized money is just as dangerous as Government by organized mob. Never before in all our history have these forces been so united against one candidate as they stand today. They are unanimous in their hate for me and I welcome their hatred."

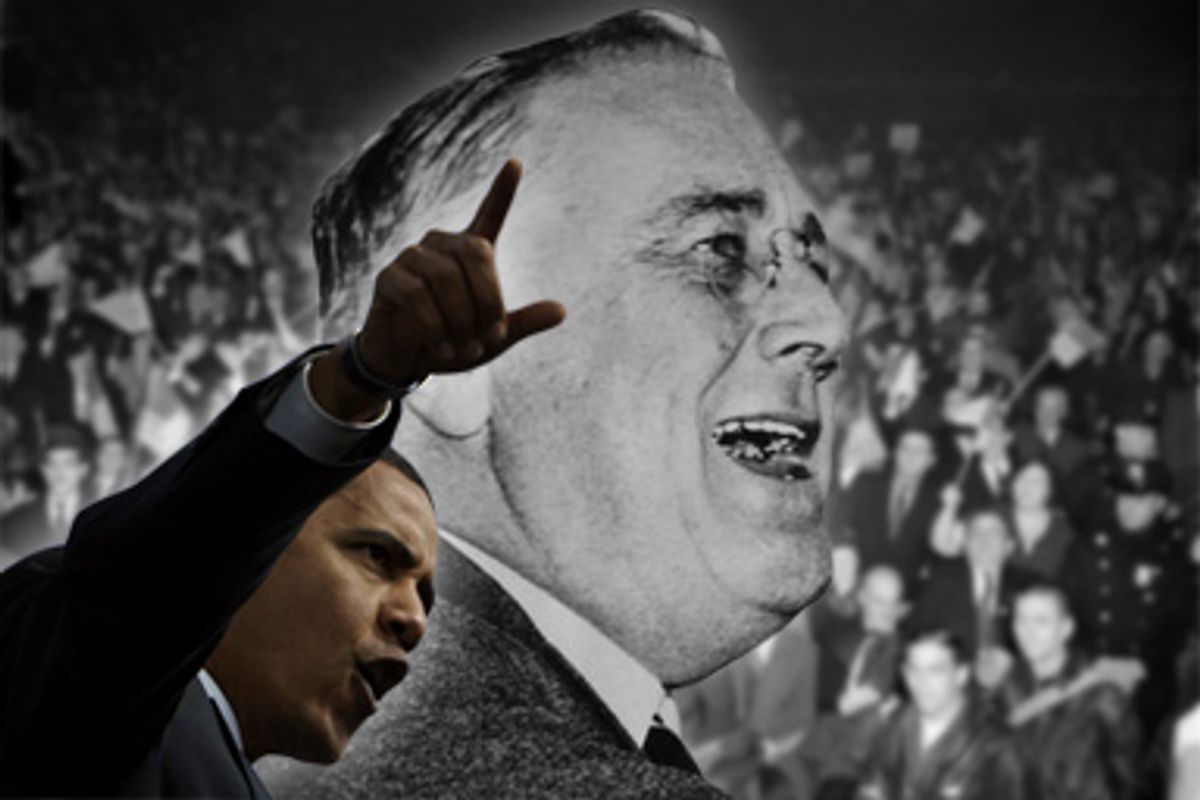

Can anyone imagine President Barack Obama saying anything like that? The nickname of Roosevelt's successor in the White House, Harry Truman, was "Give-'Em-Hell Harry." As the Republican minority, backed by an avalanche of special-interest money, mobilizes to thwart the health reform agenda of the Democratic majority, maybe the time has come for "Give-'Em-Hell Barry."

The most dangerous deficit that the United States faces is not the budget deficit or the trade deficit. It is the Democrats' demagogy deficit. Franklin Roosevelt, looking down from that Hyde Park in the sky, would not be surprised that conservatives are seeking to channel populist anger and anxiety, not against the Wall Street elites who wrecked the economy, but against reformers promoting healthcare reform and economic security for ordinary people. As he told his audience in 1936, "It is an old strategy of tyrants to delude their victims into fighting their battles for them." But FDR would be shocked by the inability of his party to mobilize the public on behalf of reform.

The irony is that the modern conservative movement started out by opposing the very populism it later embraced. The late William F. Buckley Jr. was influenced by the philosopher Albert Jay Nock, a family friend who despised mass democracy. Buckley's never-published philosophical manifesto, written in the 1950s and early 1960s (he allowed me to read the manuscript), was a critique of the mass society, inspired by the Spanish philosopher Ortega y Gasset's "The Revolt of the Masses." The symbol of empty, decadent mass politics for the young Buckley, as for Gore Vidal in his novel "Washington, D.C.," was the telegenic celebrity politician John F. Kennedy. A few years later in the 1960s, Buckley wrote that he would rather be governed by the first 400 names in the Boston phone book than by the Harvard faculty, and in 1980 the conservative movement captured the White House in the person of the ultimate telegenic celebrity master of mass politics, Ronald Reagan.

While the right was rejecting its gloomy elitism and embracing the mass society and populist politics, liberalism was moving in the other direction. Liberal intellectuals, shocked by McCarthyism and the rejection by the voters of the urbane Adlai Stevenson for Dwight Eisenhower, concluded that the American people themselves were the problem. In "The Age of Reform" and other works, the influential liberal historian Richard Hofstadter argued that the Progressive and Populist movements, far from being the precursors of New Deal liberalism, were reactionary movements by downwardly mobile professionals or farmers suffering from "status anxiety." Seymour Martin Lipset and other sociologists and historians including Daniel Bell and Peter Viereck argued that many members of the working class had "authoritarian personalities" and that populism here as in Europe could lead to fascism. Although more accurate historians and pollsters demolished their caricature of working-class Americans as proto-Nazis suffering from "status anxiety," the damage had been done. The New Left of the 1970s and 1980s, clashing with socially conservative blue-collar "hard-hats," were if anything even more hostile to the white working class, and sought allies instead among blacks, immigrants and various "social movements," most of them staffed and run by members of the college-educated upper middle class.

Whereas progressives and populists alike had been able to invoke the people against the interests, the mid-century liberals and many of their successors on the center-left to this day fear the people even more than they fear the interests. They worry that if liberals rile up the crowd against Wall Street, the rampaging mob, like the torch-bearing Transylvanian villagers in the old Universal Pictures Frankenstein movies, might turn on the universities or carry out political pogroms against minorities. When passion and polemic are ruled out as uncivil, when appeals to the people and their tradition are ruled out by liberalism's own theory of itself, it is hard to see how there can be a popular liberal politics, as distinct from a politics of brokering among interests or elite reforms from above. It follows that liberals should focus on keeping the public calm, while carrying out reforms on their behalf -- but without their participation -- on the basis of negotiations among politicians, public-spirited nonprofit activists, and enlightened interest groups. The Obama administration's approach to healthcare reform has followed this script exactly.

The two arguments on which the administration has rested the case for healthcare are calculated to appeal to elites, not the general public. One argument holds that it is immoral to allow a substantial minority of Americans, who are disproportionately poor, to lack health insurance. This argument appeals to progressive Democrats in the academic and nonprofit communities for whom politics is a form of charity. The other argument is that healthcare cost inflation will wreck the economy in the future, unless it is brought under control. This argument appeals to the Wall Street donor wing of the party, symbolized by Robert Rubin, whose protégés, including Larry Summers, Timothy Geithner and Peter Orszag, surround Obama in the White House.

But if you are trying to mobilize public support for a sweeping healthcare overhaul, appealing to charity or the concerns of bondholders is not the way to go about it. "Vote your interests!" Harry Truman told Americans in 1948. Most Americans have employer-provided healthcare. They are worried about keeping it if they lose their jobs and about the rising cost of deductibles. Democrats should have sold healthcare reform as establishing a permanent, universal right to affordable healthcare.

You also can't fight and win a war without naming your enemies. In the case of healthcare, the enemies of the American people -- if I may be demagogic as well as accurate -- include rent-seeking insurance companies, rent-seeking pharma companies, and overcompensated doctors and hospitals.

Last but not least, you need a narrative in which today's campaign is not an isolated technocratic attempt to solve a particular public policy problem, but part of the ongoing story of progressive reform in America. In his 1964 Democratic convention speech, Lyndon Johnson invoked American history in laying out the vision of the Great Society: "The Founding Fathers dreamed America before it was. The pioneers dreamed of great cities on the wilderness that they crossed." It's hard to make that appeal if you agree with elements of the academic left that the Founders were self-seeking crooks, that the pioneers were genocidal monsters and that great cities on the wilderness are ecological disasters. The consensus liberals of the mid-20th century and the multicultural liberals of the late 20th century have been too busy exaggerating the anti-Semitism of 19th-century populists or emphasizing the racist attitudes of the 19th-century labor movement to invoke the ideals those precursors share with post-racist 21st-century liberals. But we can be inspired by the universal ideals that we share with our predecessors without endorsing or excusing their parochial prejudices.

A Rooseveltian or Trumanesque campaign speech, addressing the concerns of the American majority, invoking the heroic history of American reform and naming the enemy, practically writes itself:

"My fellow Americans, we say that healthcare is a right of all citizens. The other party says that it is a privilege for those who can afford it. If you agree with them that healthcare is a privilege, not a right, then vote for them. We would like to persuade you to join us, but if we can't, then we are going to defeat you.

"Decades ago our opponents tried to block Social Security and Medicare, using the same bogus arguments that they are using today against healthcare reform. They said Social Security and Medicare would bankrupt the country. They were wrong. Once we fix the cost inflation of our broken medical sector, with some minor tweaks Social Security and Medicare can be made solvent forever.

"Decades ago, our opponents said that Social Security and Medicare would turn the United States into a fascist or communist police state. They were wrong then and they are wrong now. And not only are they wrong, they are hypocritical. Many of our opponents who claim absurdly that universal healthcare will bring tyranny to the U.S. have defended some of the greatest assaults on civil liberties and the rule of law in American history during the previous administration.

"They can draw a Hitler mustache on me. They can draw a mustache on the Mona Lisa, for all I care. They are wrong and we are going to defeat them.

"We won the elections and we are the majority. We would like to build the biggest consensus possible, but progress is more important than consensus. Our job is to help the American people, not split the difference between right and wrong by giving a veto to the party that the American people have rejected.

"In this fight, as in earlier struggles, powerful interests are opposed to the needs of the people. In the 19th century, we the people defeated the Southern slave owners, freed the slaves and saved the nation. In the 20th century, while fighting alongside many other nations to save the world from militarism and totalitarianism, we the people here at home tamed the corporations for a generation and fought segregation based on race, gender and, more recently, sexual orientation.

"Today the campaign for affordable healthcare as a right, not a privilege, is opposed by powerful interests in the medical and insurance industries. They seek to deceive and confuse you. And they seek to bribe or intimidate your elected representatives into serving their will rather than the needs of the public.

"They may win this battle. They may win the next. But we will never stop fighting for the needs of the many against the greed of the few. For more than 200 years, from the time we threw off the tyranny of the British empire and established our republic, we have worked to realize the spirit of '76 on this continent and in the world beyond. The enemies of progress have money on their side. We have history on ours."

If Barack Obama can speak in accents like these, then he will be able to declare, like Franklin Roosevelt in 1936, "I should like to have it said of my first Administration that in it the forces of selfishness and of lust for power met their match. I should like to have it said of my second Administration that in it these forces met their master."

Shares