American political discourse has gotten increasingly nasty over the past 10 months, with brutal rhetoric spilling from talk radio to town hall meetings to the very halls of Congress. When anti-government protesters openly carry loaded weapons at rallies and Texas Gov. Rick Perry hints at the possibility of secession, you might wonder whether the nation is actually at the brink of civil war over the unlikely issue of healthcare reform. Sadly, the commentators and politicians who exploit such threats of violence and revolution seem to have forgotten what the real Civil War was about, and what it was like. Now would be a good time to start remembering, because, as it happens, the first pitched battle of our bloodiest war began exactly 150 years ago today.

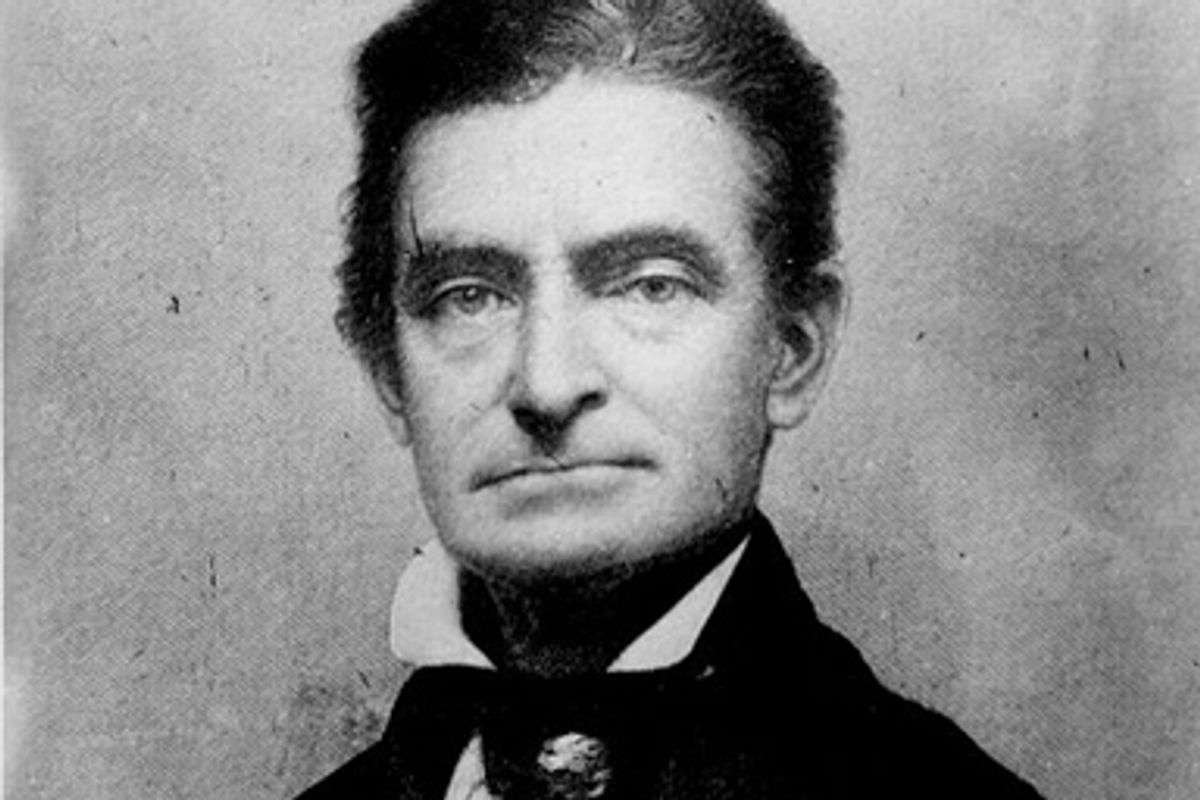

On Sunday night, Oct. 16, 1859, John Brown and a troop of 18 men entered the sleeping town of Harpers Ferry, Va., where they began an assault on slavery that would lead first to civil war and eventually to emancipation. They quickly took control of a federal arsenal, but shots were fired in the encounter, killing a black railroad worker and alerting the town that a raid was under way. By mid-morning the following day, Brown and his men were surrounded by local militia whose constant fire killed many of the raiders.

Late Monday, Oct. 17, a detachment of federal Marines arrived under the command of Robert E. Lee, and Brown's fate was sealed. At dawn on Tuesday morning, only five of Brown's men remained standing -- several had fled and the others were dead or gravely wounded. When Brown refused a demand to surrender, a squadron of Lee's troops stormed the armory. Brown was taken alive along with four other survivors.

Brown was turned over to the state of Virginia for prosecution. He was soon indicted on the capital counts of murder, inciting servile rebellion, and treason against the state of Virginia. Gov. Henry Wise had decided to use the prosecution as a means to assail the entire abolitionist movement, and the indictment therefore blamed the raid not only on Brown, but also on the "counsel of other evil and traitorous persons."

John Brown, too, understood the potential political impact of his trial. Refusing secret offers to organize his rescue, he explained that "I cannot now better serve the cause I love so much than to die for it; and in my death I may do more than in my life." Then Brown set about orchestrating the events leading up to his own execution, using the courtroom as a platform from which he could explain and justify his war on slavery.

In the days immediately following the raid, Brown had been disowned by leaders of the abolitionist movement, nearly all of whom were fearful of being tarred by association. Republican newspapers referred to Brown as a "solitary madman," and a "lawless brigand." When he was finally given an opportunity to address the court, however, Brown's deeply emotional speech succeeded in stirring northern consciences and, astonishingly, turning the reviled leader of a suicidal raid into an abolitionist hero.

The trial itself was held in nearby Charlestown, beginning on Oct. 26. The evidence against Brown was overwhelming, with numerous witnesses recounting the killings committed by his men. Following a day of procedural motions and four days of testimony, it took the jury only 45 minutes to return a verdict of guilty on Monday, Oct. 31. Sentencing was set for the following Wednesday morning.

The defendant appeared almost serene when court reconvened. The trial judge did not anticipate what was coming when Brown was asked whether he "had anything to say why sentence should not be pronounced upon him."

Brown arose and delivered a ringing attack on slavery. "This Court," he said, "acknowledges, too, as I suppose, the validity of God's law," which teaches us "to remember them that are in bonds." In attempting to free slaves, he declared, "I did no wrong, but right. Now if it is deemed necessary that I should forfeit my life for the furtherance of the ends of justice, and mingle my blood further with ... the blood of millions in this slave country whose rights are disregarded by wicked, cruel and unjust enactments, I say, let it be done."

Brown's speech drew convulsive reactions on both sides of the Mason-Dixon line. In the North, significant public opinion swung behind Brown, who was suddenly seen as a martyr to the slave power. Henry David Thoreau, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Wendell Phillips all gave lectures lauding Brown. More than anything else, a phrase of Emerson's captured and intensified reaction to Brown's transformative speech, describing him as, a "new saint" who "will make the gallows glorious like the cross."

Abolitionists in the North were energized, but Southerners were universally enraged, using the occasion to demonize not only Brown but also every political figure associated with the anti-slavery movement. Jefferson Davis, then a senator from Mississippi, called for New York Sen. William Seward (later Lincoln's secretary of state) to be hanged for supposedly encouraging Brown's raid.

After decades of mistrust and recrimination over the conflict between slavery and free labor, many in the North and South now found themselves even more fundamentally at odds. As Northerners increasingly hailed Brown as a hero, panicky Southerners execrated him as the devil himself. The tempest over John Brown appeared to shatter any hope of regional reconciliation. As one South Carolina editor put it, "The day of compromise is passed [and] there is no peace for the South in the Union."

It would be too much to claim that John Brown's raid made the Civil War inevitable. But it is fair to say that it helped to create an unbridgeable gap between the free states and the slave power that could only be, as Brown himself put it, "purged away with blood." There are many lessons that can be drawn from John Brown's raid, but the experience of the Civil War ought to stand as a permanent rebuke to the irresponsible incitement of contemporary political figures who trade so easily in rage and resentment.

Shares