On Monday, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that "enemy combatants" -- prisoners seized in the "war on terror" who the Bush administration argued had no legal recourse -- have the right to challenge their detention in American courts. Writing for the majority, Justice Sandra Day O'Connor wrote, "A state of war is not a blank check for the President when it comes to the rights of the Nation's citizens."

Somewhere in the San Francisco Bay Area, a soft-spoken man named Fred Korematsu is smiling.

Americans assume that their civil rights are sacrosanct, that civic tradition and the Constitution are a sure bulwark against the state's power to treat them without due process. They're wrong. Civil rights are only as strong as the nation's commitment to defending them. And the grim truth is that during wartime, that commitment often fails -- especially when the gasoline of racism is poured onto the flames of fear.

That is true today, as the dark-skinned prisoners in Guantánamo and the thousands of harmless Arabs and Muslims deported or harassed after 9/11 can attest. And it was true in 1942, when Fred Korematsu, along with 120,000 other law-abiding Americans of Japanese ancestry -- two-thirds of them American citizens -- were forcibly removed from their homes, farms, businesses and communities and sent into imprisonment in desolate camps throughout the West. Their crime? Being of Japanese descent. It was the greatest mass violation of civil rights in 20th century American history.

Fred Korematsu resisted the order. He took his case to the Supreme Court. Of the four Supreme Court cases brought by Japanese-Americans involving the internment order, his was the only one in which the court directly ruled on the constitutionality of the relocation order. In what is now regarded as one of the most disgraceful rulings in the court's history, he lost -- and to this day, the right of the government to act as it did in 1942 has never been overturned. But his defeat carried within it the seeds of a larger victory. Forty-one years later, a legal team made up of mostly young Japanese-American lawyers -- many of whose parents had been in the camps -- brought suit to bring justice not just to Korematsu, but also to all those who had been wronged by the internment orders. In a stunned and tearful California courtroom, his conviction for refusing to report to an "assembly center" was overturned, and the shame of a dark moment in American history was finally washed away.

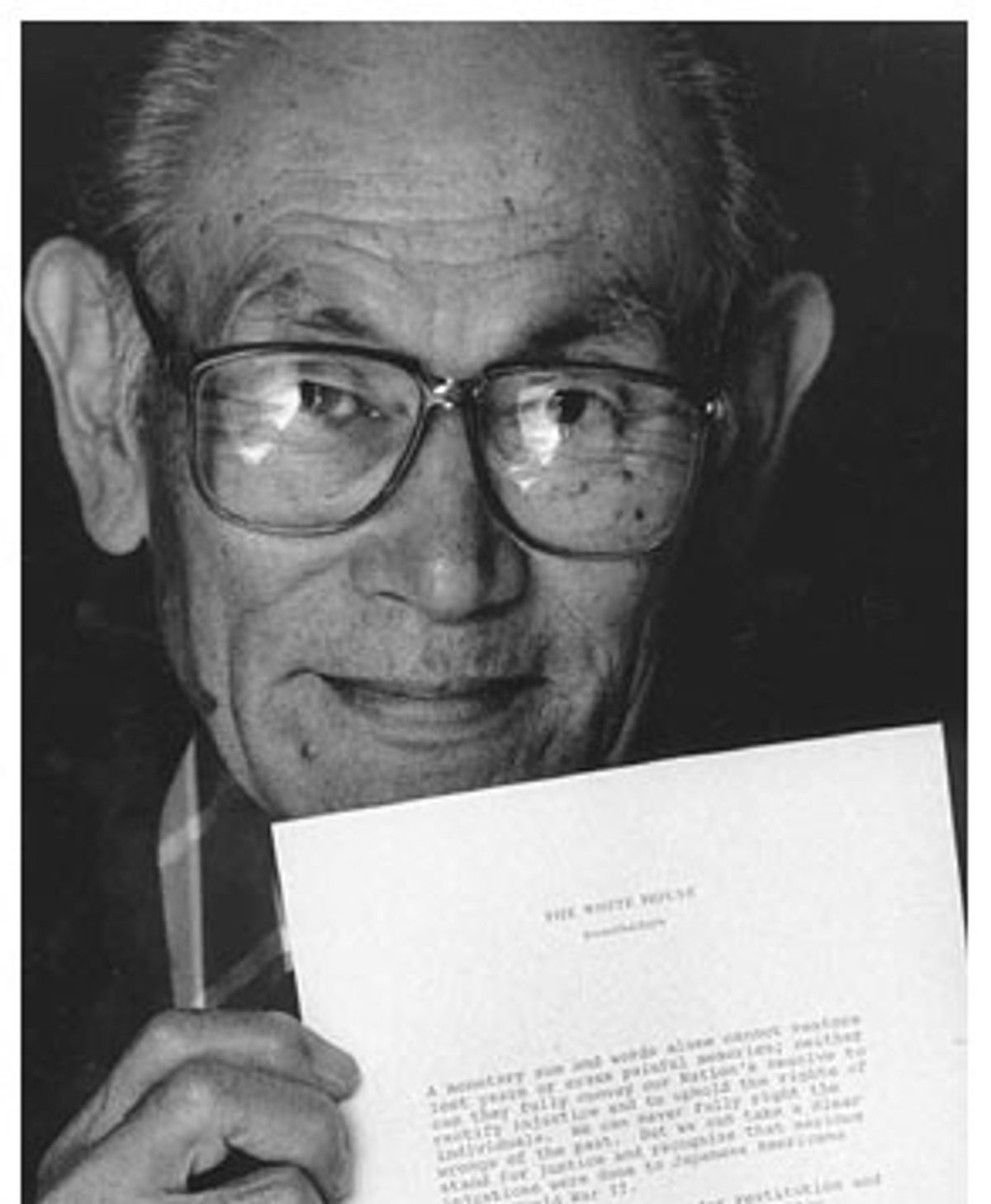

Five years later, President Bill Clinton awarded Korematsu the nation's highest civilian award, the Presidential Medal of Freedom. That award recognized that the unassuming young welder had stood up for something larger than himself. Fred Korematsu, who would not go into the camps, had joined Rosa Parks, who would not give up her seat, in the most exclusive, yet most universal, American club: the club of ordinary heroes.

"We should be vigilant to make sure this will never happen again," Korematsu said upon receiving the Medal of Freedom. And he has practiced that vigilance himself. Last October, he joined a friend-of-the-court brief to the Supreme Court, arguing that the extended executive detentions of "enemy combatants" are unconstitutional. Few amicus petitioners have carried more moral authority.

The event that was to change Fred Korematsu's life forever took place on Feb. 19, 1942, a little more than two months after Pearl Harbor. That was the day that President Franklin Delano Roosevelt -- acting under pressure from military authorities, the media and West Coast political leaders -- signed Executive Order 9066, authorizing the mass evacuation of 120,000 Americans of Japanese ancestry from the West Coast. The reason given was that the Japanese constituted a military threat. No evidence was ever presented for this claim. Roosevelt did not discuss the order with his cabinet, nor did he ask for justification.

Among the thousands of those affected was the Korematsu family, which ran a nursery in Oakland. The elder Korematsus, like almost all other Americans of Japanese descent, planned to obey without protest. But their son, 22-year-old Fred Korematsu, took a different view. He thought it was wrong and unfair that he should be forced to abandon his home and be sent to a far-off prison camp simply because of his race. After talking things over with his parents and his Italian-American girlfriend, he decided not to go. He was one of only a handful of Japanese-Americans who refused to comply with the internment order.

Korematsu, who had been working as a welder in a shipyard, changed his name and had minor plastic surgery to make himself look less Japanese. He succeeded in avoiding the authorities for about three months, but on May 30, 1942, someone recognized him in a San Leandro store and called police. He was arrested and sent to Tanforan Race Track, where Japanese-Americans were processed (sleeping in horse stalls reeking of manure) before being shipped off to various desolate camps on the wind-swept plateaus of the West. Korematsu was sent to the internment camp at Topaz, Utah.

Before he departed, however, he was visited in jail by a man named Ernest Besig, the executive director of the Northern California chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union. He had read about Korematsu in the paper. He had been looking for a Japanese-American who would challenge the legality of the internment order -- a test case. Besig was acting without institutional sanction: the national ACLU, intimidated by war fervor, had decided not to challenge the constitutionality of the internment. He asked the young man if he would agree to go to court.

Korematsu was utterly alone. His family was already gone. His girlfriend was, too -- in fact, he never saw her again. His community was scattered. The conservative Japanese American Citizens League, the sole group representing both Issei (Japan-born Americans, forbidden by racist U.S. law from becoming citizens) and Nisei (their American-born children) had decided for strategic reasons to go along quietly with whatever the authorities ordered. By fighting the government, Korematsu risked alienating himself from his peers, many of whom had decided that the only way to prove their loyalty was to keep their heads down.

Korematsu agreed to fight the government in court. In October 1944, with World War II heading into its brutal final winter, Korematsu's case reached the Supreme Court. The government's lawyers argued that in wartime, the military was required to take all steps necessary to protect the national security. It cited a report by General DeWitt, the officer responsible for the defense of the West Coast (and whose recommendation was responsible for Executive Order 9066), claiming that many people of Japanese ancestry were disloyal and that there was no time to figure out which of them were loyal and which were not.

Korematsu's lawyers charged that the evacuation orders were transparently racist and denied an entire class of people due process and equal protection under the law. They pointed out that not a single episode of espionage or sabotage had taken place during the four months between Pearl Harbor and General DeWitt's first evacuation order. (This fact did not faze DeWitt, who in his "Final Report: Japanese Evacuation From the West Coast" boldly made the Orwellian argument that "the very fact that no sabotage or espionage has taken place to date is disturbing and confirming indication that such action will take place.") They argued that DeWitt was himself a racist, citing this statement he made in 1943 before a congressional committee:

"A Jap's a Jap. It makes no difference whether he is an American citizen or not. I don't want any of them ... They are a dangerous element, whether loyal or not."

DeWitt's viewpoint was probably shared in some form by most Americans. At bottom, the fear was of a racially tinged "clash of civilizations": the Japanese were mysterious and opaque, not "real" Americans, and when the chips were down they were likely to betray their new nation in favor of their race. This belief was eloquently expressed by none other than Earl Warren, the California attorney general who was later to become the famously liberal chief justice of the United States. Testifying in 1942 before a House committee, Warren said, "the consensus of opinion among the law-enforcement officers of this State is that there is more potential danger among the group of Japanese who are born in this country than from the alien Japanese who were born in Japan. We believe that when we are dealing with the Caucasian race we have methods that will test the loyalty of them, and we believe that we can, in dealing with the Germans and Italians, arrive at some fairly sound conclusions because of our knowledge of the way they live in the community and have lived for many years. But when we deal with the Japanese we are in an entirely different field and we can not form any opinion that we believe to be sound."

This, then, was the intellectual climate in which the Supreme Court heard the case. On Dec. 18, 1944, the court handed down its decision. The divided court (6-3) ruled against Korematsu. In his majority opinion, Justice Hugo Black essentially deferred to the military authorities and Congress, who had stated that the presence of an uncertain number of disloyal Japanese made it necessary to remove all of them from the coast. Quoting the Court's opinion in Hirabayashi, an earlier case involving a Japanese-American who knowingly violated a curfew, Black wrote, "We cannot reject as unfounded the judgment of the military authorities and of Congress that there were disloyal members of that population, whose number and strength could not be precisely and quickly ascertained. We cannot say that the war-making branches of the Government did not have ground for believing that in a critical hour such persons could not readily be isolated and separately dealt with, and constituted a menace to the national defense and safety, which demanded that prompt and adequate measures be taken to guard against it."

Black denied that racism lay behind the relocation order, only military necessity. But neither he nor the rest of the majority seemed interested in trying to find out just what that military necessity was. Certainly little evidence, and no convincing evidence, was advanced of Japanese-American disloyalty. (In fact, not a single case of sabotage or espionage by Japanese-Americans ever took place during the entire war.) Black cited the fact that 5,000 internees refused to swear unqualified allegiance to the United States, overlooking the fact that their forcible removal from their homes and businesses without legal recourse might have had something to do with their refusal. Nor did he deal with the uncomfortable fact that neither Italian-Americans nor German-Americans were evacuated from their homes and forced into prison camps.

It is difficult to escape the conclusion that Black, who was a former member of the Ku Klux Klan, subscribed at some level to the same racist beliefs that infected so many other Americans. Why else would he have so uncritically accepted the feeble national-security arguments advanced by the government?

Whatever his motivations, it was a decision that was reportedly to haunt Black for the rest of his life. After all, Black was one of the court's greatest defenders of civil liberties, author of the now-classic decision in the landmark Pentagon Papers case. (Ironically, the most towering civil liberties advocate in court history, Justice William O. Douglas, concurred with the majority in Korematsu.) But though troubled by the ruling, Black was never able to bring himself to admit he was wrong. In a 1967 interview, Black said, "I would do precisely the same thing today, in any part of the country. I would probably issue the same order were I President. We had a situation where we were at war. People were rightly fearful of the Japanese in Los Angeles, many loyal to the United States, many undoubtedly not, having dual citizenship -- lots of them. They all look alike to a person not a Jap. Had they [the Japanese] attacked our shores you'd have a large number fighting with the Japanese troops. And a lot of innocent Japanese-Americans would have been shot in the panic. Under these circumstances I saw nothing wrong in moving them away from the danger area."

In a biting dissent, Justice Frank Murphy called the ruling "a legalization of racism." But Korematsu had lost.

The war ended and Korematsu, along with thousands of other internees, got out of the camps and on with his life. He did not like to talk about his Supreme Court case; in fact, his own daughter only learned about it in class. He wanted to reopen his case but didn't know how. It was not until 1983 that his now-ancient legal battle stirred again.

As recounted in Eric Paul Fournier's moving 2000 documentary "Of Civil Rights and Wrongs," which with Steven Okazaki's "Unfinished Business" offers a powerful account of Korematsu's fight, a San Diego historian and law professor named Peter Irons made the kind of discovery that historians, lawyers and journalists can only dream about: He came upon documentary evidence proving that the government had knowingly lied to the Supreme Court in the original Korematsu case.

In researching a book on the internment cases, Irons made a request to the National Archives for the actual case files, which had been misfiled. "It was just by chance that one slip of paper survived stating where the cases were," Irons says in the film. "In fact, they were sitting in three cardboard boxes that were covered with dust, tied up with string. And it was obvious that I was the first person in more than 40 years who'd looked at these files. I knew that there would be a lot of case material, the kind of stuff that lawyers produce -- memos, briefs, things like that. What I did not expect to find was literally on the top of the first file, a document from one of the Justice Department lawyers to the Solicitor General of the United States saying we are telling lies to the Supreme Court. We have an obligation to tell the truth to the court."

The documents showed that the solicitor-general of the United States, Charles Fahy, knew that all of the military's arguments that Japanese-Americans were engaging in subversive behavior were contradicted by reports from the FBI and military intelligence -- and failed to share that information with the court. Smoking guns don't get much more billowing.

Irons visited Korematsu at his San Leandro home and showed him the documents. Korematsu sat in silence for 15 or 20 minutes, puffing on his pipe, reading the documents. Then he asked Irons, "Are you a lawyer?" Irons said he was. "Would you be my lawyer?"

And so the battle was joined again. This time, Korematsu would win.

A legal team led by Irons and a young Sansei (third-generation Japanese-American) lawyer named Dale Minami filed a coram nobis petition on Korematsu's behalf in a San Francisco district court. "Coram nobis" is Latin for "before us": Like the related writ of habeas corpus, which protects against illegal detention, coram nobis applies to those individuals who have been convicted wrongfully and have served their sentence. To prove coram nobis, the petitioner must show that a fundamental error or manifest injustice has been committed. Only egregious errors of fact or prosecutorial misconduct, not interpretations of the law, will result in a successful coram nobis writ.

Fortunately, that is exactly what Korematsu's attorneys had. In fact, so incendiary were the documents that the lawyers feared they would "disappear"; they met in secret for many months. The team made a tactical decision to file in the District Court, rather than to the high court, because there was a much greater chance they would lose in the Supreme Court.

The government, clearly aware that it was doomed, stalled, arguing about procedure. It offered Korematsu a pardon -- which of course implies guilt. Korematsu refused.

Finally the judge hearing the case, Marilyn Hall Patel, grew impatient with the government's delaying tactics. She asked the lead government attorney whether the government was going to oppose the petition or agree to it. The attorney said he didn't have the authority to make that decision. She told him to go call someone "right now" who did have that authority. He came back and said he still couldn't make that decision. At this point, Patel decided that the government had in effect confessed error, "even though they don't say in those magic incantation words 'we confess error.' They had done substantially the same thing." She prepared a substantive decision to read in the courtroom the next day, knowing that it would be packed with people.

The next day, the government made its arguments. It argued that the case should not be reopened because to do so would be to reopen old wounds. There was no reason to go back and try to find out what actually happened back then, the government said -- why not just let bygones be bygones?

Minami responded by pointing out that the only "old wounds" that would be reopened would be those of a government that had lied to the Supreme Court, not those of people who had already lost their homes and livelihood. Then he asked if Fred Korematsu could make a short statement.

Korematsu said that 41 years ago, he entered this courtroom in handcuffs and was sent to a camp that was not fit for human habitation. Horse stalls are for horses, not people. He asked the court to overturn his conviction, saying, in Minami's recollection, "that what happened to him could happen to any American citizen who looks different or who comes from a different country and that it was important for this court to understand that the relief given to him was not just for him personally, but in a sense, for the benefit of the whole country."

When Korematsu finished, Patel read her ruling to the courtroom right from the bench. She said that there was sufficient evidence of governmental misconduct to overturn the conviction. Evidence had been suppressed. The policies of the U.S. government were infected with racism. She said that the Constitution had to be protected at all times for all people. Then she got up and left the court.

For a moment, after she left, the entire audience was stunned. History had been made in front of their eyes: a great injustice had been legally expunged. But it was too big to take in. Korematsu asked someone, "What happened?" He was told, "You won." Then it sank in. The crowd, many of them camp survivors, was overcome with emotion. They swarmed Korematsu, hugged him. Tears flowed -- but this time they were tears of vindication. The young shipyard welder's long odyssey had finally ended. He had carried not just himself, but also his people, into the safe harbor of belated justice. That justice did not make up for lives shattered, property lost, hopes blighted. But it helped.

Korematsu's victory was not complete. The Supreme Court ruling in his case has never been overturned; it remains on the books, like a malignant virus, waiting to be activated when racist paranoia and war hysteria sweep aside Americans' commitment to civil rights. Every generation seems condemned to fight the same battles on different grounds: Guantánamo is today's Heart Mountain. But the knowledge that ordinary people like Fred Korematsu are there, willing to stand quietly up for their rights, makes it possible to dream that one day the battle will be won.

Shares