President Bush's political strategy at home is an implicit if unintended admission of the failure of his military strategy in Iraq and toward terrorism generally. Betrayal is his theme, delivered in his speeches, embroidered by his officials and trumpeted by the brass band of neoconservative publicists. The foundation for his stab-in-the-back theory was laid in the beginning.

"Either you are with us or you are with the terrorists," Bush said in his joint address to Congress nine days after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks. And in the weeks that followed he repeated variations of his formula, reducing it to "for or against us in the war on terrorism." At the Charleston, S.C., Air Force Base on Tuesday, Bush resumed his repudiated habit of conflating threats, suggesting a connection between 9/11 and the Iraq war, and intensified his blaming of domestic critics for the shortcomings of his policy. His story line depends upon omitting his own part in the calamity. "The facts are," insisted Bush to his captive audience, "that al-Qaida terrorists killed Americans on 9/11, they're fighting us in Iraq and across the world, and they are plotting to kill Americans here at home again."

But how did it happen that al-Qaida in Iraq, sworn enemy of Saddam Hussein and his secularism, operating in isolation prior to 9/11, though almost certainly with the connivance and protection of Kurdish leader and current Iraqi President Jalal Talabani, has come to thrive under the U.S. occupation? And since AQI represents perhaps 1 percent or less of the insurgent strength, how can it be depicted as the main foe, capable of seizing state power? The other Sunni insurgent groups increasingly view it as an impediment to their own ambitions and have marked it for elimination. Rather than address these problematic complexities, Bush points the finger of blame at U.S. senators who dare to question his policy. "Those who justify withdrawing our troops from Iraq by denying the threat of al-Qaida in Iraq and its ties to Osama bin Laden ignore the clear consequences of such a retreat."

Bush's accusation of betrayal anticipates the September report of Gen. David Petraeus on the progress of the "surge" in Iraq. The absence of victory inspires a search for an enemy within. Bush's stab-in-the-back theory is the latest corollary to the old policy that military force will create political success. Bush is a vulgar Maoist: "Political power comes from the barrel of a gun," said Chairman Mao. But the surge is simply an endlessly repetitive reaction to the failure of the purely military. Somehow, in the political vacuum, additional U.S. troops are supposed to quell the civil war, compel the sects and factions to lie down like lambs, and destroy AQI. U.S. ambassador Ryan Crocker last week begged that the Iraqi government not be held accountable for meeting political benchmarks, none of which have been realized; and at the same time he requested exit visas for his Iraqi staff, who obviously have no confidence in the Bush policy and do not wish to leave via the embassy roof. Crocker's actions speak louder than his words -- and louder than Bush's.

Bush, however, clings to the rhetoric of conventional warfare, of "victory" and "retreat." The collapsed Iraqi state, proliferation of sectarian warfare and murderous strife even among Shiite militias bewilder him; clear-cut dichotomies are more comforting, producing deeper confusion. The friend of his enemy is his friend; the enemy of his enemy is not his friend. Meanwhile, Bush seeks to displace responsibility for the potentially dire consequences of his policy on others.

Neoconservative publicists spread the calumnies that critics of Bush's policy are against the troops and that these critics will be responsible for genocide if they and not Bush are followed. William Kristol, editor of the Weekly Standard -- whose July 15 article in the Washington Post, "Why Bush Will Be a Winner," Bush has recommended to his White House staff -- has published a new piece in the latest issue of his magazine, "They Don't Really Support the Troops." "Having turned against a war that some of them supported, the left is now turning against the troops they claim still to support," he writes. His combination of nuance and crudity is ideologically deft. By pointing out that "some of them supported" the war at the start, his intention is not to draw distinctions but to lump all critics together as now undifferentiated and discreditable -- "the left." Then he ascribed a common motive: fear that Bush will succeed and a hatred of the soldiers. "They sense that history is progressing away from them -- that these soldiers, fighting courageously in a just cause, could still win the war, that they are proud of their service, and that they will be future leaders of this country." But this is not enough for Kristol. "The left slanders them. We support them. More than that, we admire them." Slander?

Jonah Goldberg, a columnist for the Los Angeles Times, writes in an article Tuesday that "liberals" are the ones responsible for a coming "genocide" in Iraq. "But if genocide unfolds in Iraq after American troops depart, it would be hard to argue that we weren't at least partly to blame. Yes, the mass murder would have more immediate authors than the United States of America, but we would undeniably be responsible, at least in part, for giving a green light to genocide." Having initially adopted a vague "we," he quickly dispenses with this rhetorical strategy, blaming "liberals" and one person in particular for "mass murder." Barack Obama "offers precisely that green light," he writes.

On July 16, the Associated Press reported on a letter from Undersecretary of Defense for Policy Eric Edelman to Sen. Hillary Clinton, condemning her for deigning to request in her capacity as a member of the Armed Services Committee information on Pentagon contingency plans for withdrawal. "Premature and public discussion of the withdrawal of U.S. forces from Iraq reinforces enemy propaganda that the United States will abandon its allies in Iraq, much as we are perceived to have done in Vietnam, Lebanon and Somalia," Edelman replied. Even asking about such plans aids and abets the enemy, tantamount to treason. Edelman added the suggestion of a massacre if we "abandon" the "allies," and said its responsibility would fall on those who raised questions.

In response to a letter from Sen. Clinton, asking if Edelman's statement "accurately characterizes your views as Secretary of Defense," Robert Gates in effect repudiated it. "I have long been a staunch advocate of congressional oversight, first at the CIA and now at the Defense Department," he wrote on July 20. "I have said on several occasions in recent months that I believe that congressional debate on Iraq has been constructive and appropriate. I had not seen Senator Clinton's reply to Ambassador Edelman's letter until today."

Gates' note is extraordinary not only for its open acknowledgment of a breach with his undersecretary but also for its revelation that he was unaware of Edelman's vitriolic letter. Edelman is a longtime neoconservative with deep ties to Dick Cheney. Like John Bolton, who served as a counterintelligence agent for Cheney when he was undersecretary of state under Colin Powell, Edelman does not truly serve his immediate superior in the chain of command. His ultimate allegiance is pledged to an ideological network. Given the incendiary nature of his letter to a Democratic presidential candidate, which could only be conceived and interpreted as supremely political, it's hard to imagine that as seasoned an operator as Edelman would act entirely on his own. But if he did not brief and receive approval from Gates -- and Gates has gone out of his way to distance himself from any involvement -- then whom did Edelman discuss his letter with before he sent it?

Edelman is a rare Foreign Service officer long aligned with neoconservatives. As he explained in his letter of April 21 to Judge Reggie Walton requesting clemency in sentencing for I. Lewis Libby, Cheney's former chief of staff, he has known Libby, "a deeply dedicated public servant," for 26 years. Edelman first served with Libby, he wrote, during the Reagan administration, followed by service as Libby's deputy in the Defense Department during the elder Bush's administration, under Secretary of Defense Cheney, and most recently as Libby's deputy on Cheney's staff.

Edelman, in fact, was the first person on Cheney's staff to sound the alarm against former ambassador Joseph Wilson after reading the May 6, 2003, column by Nicholas Kristof in the New York Times that described Wilson but did not name him. Edelman urged Libby to leak information to rebut Wilson's disclosure that it was a request from the vice president's office that initiated his mission to Niger in search of the phantom yellowcake uranium Bush claimed Saddam was purchasing -- a major rationale for the Iraq war.

This year, Edelman leapt to the defense of the prewar disinformation campaign operated out of the Pentagon through a small unit called the Office of Special Plans and run by Edelman's predecessor in his current post, the neoconservative Douglas Feith. When the Defense Department's inspector general, Thomas Gimble, issued a report in February calling Feith's operation "inappropriate" and urging that new controls be established to prevent officials from conducting rogue "intelligence activities," Edelman countered with a heated 52-page memo calling the I.G. "egregious," charging that he "does not have special expertise" on an issue that is "fraught with policy and political dimensions." Edelman's blast succeeded in forcing the I.G. to drop his recommendations and, as Newsweek reported, "shows how current and former Cheney aides still wield their clout throughout the government."

The degree to which Edelman has been rewarded for his ideological affinities is apparent not only in his appointments but also in monetary emoluments. According to State Department records, in 2005 and 2006, he received Senior Foreign Service performance awards of $10,000 and $12,500, respectively, both standard for someone of his rank. However, in June of this year he received a Presidential Rank Award of $40,953, an amount described as "amazing" by a former senior State Department professional who has administered such awards. Indeed, the Office of Personnel Management cautions against granting Presidential Rank Awards for appointments requiring Senate confirmation and for those in their positions for less than three years. Gates signed off on this award, but Cheney loomed as Edelman's sponsor, having personally reviewed his performance evaluations from 2001 to 2003.

In addition to the accusations of betrayal involving aiding "enemy propaganda," stabbing our troops in the back just as they are about to succeed, and acting as the architects of genocide, neoconservatives also argue that if only their initial advice had been followed in installing their favorite exile, Ahmed Chalabi, as leader of Iraq, none of the subsequent problems would have occurred. Thus it would all have been a "cakewalk" as projected, if not for the occupation, for which they were not responsible. The only error the neoconservatives admit is not being vigilant against compromise and insisting on the seamless political correctness of their plan, such as it was.

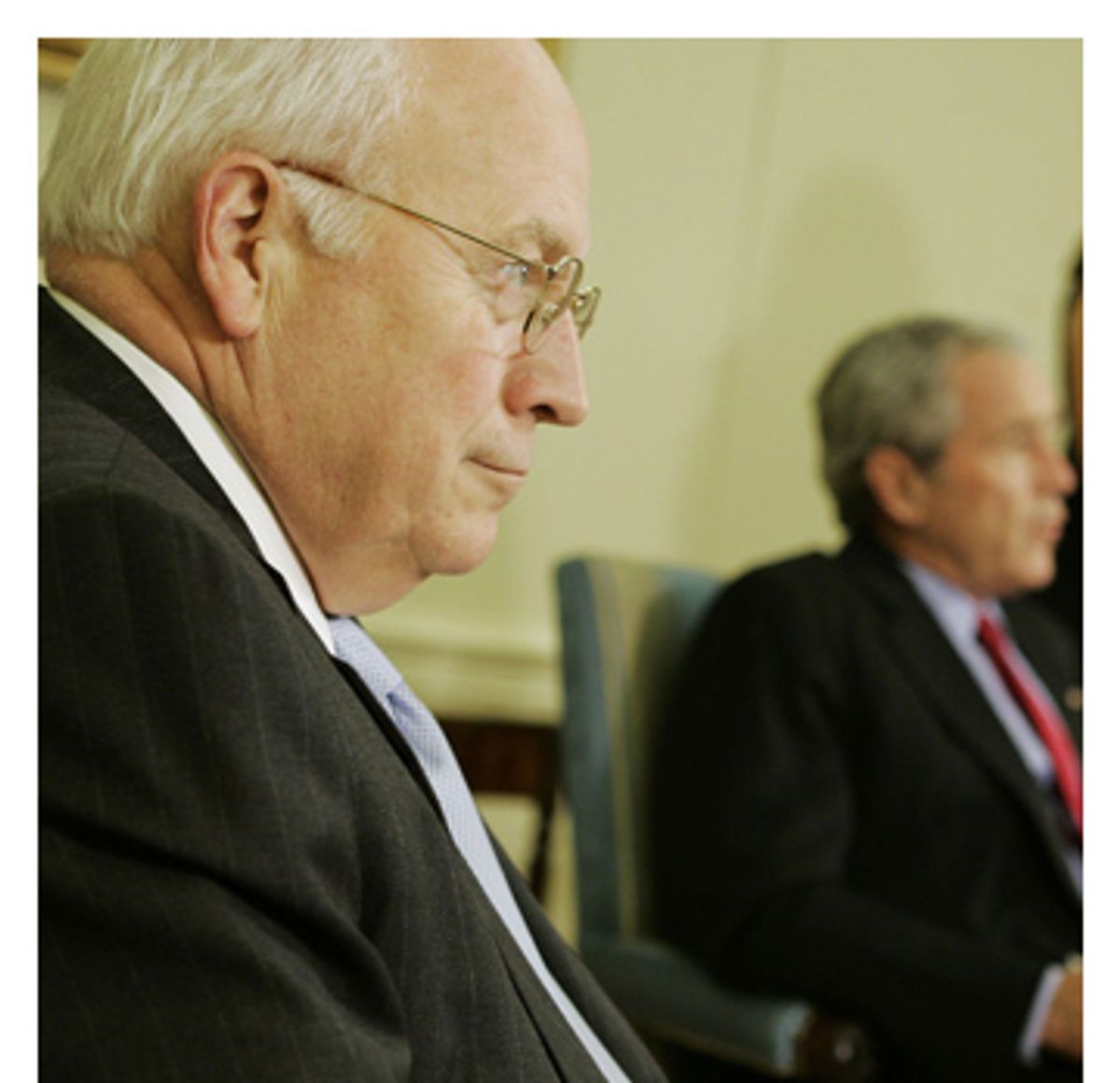

The latest personage to take up this neoconservative argument is none other than Cheney himself. "I think we should have probably gone with the provisional government of Iraqis," he says. "I think the Coalition Provisional Authority was a mistake." The vice president's remark appears in a new, authorized biography, "Cheney: The Untold Story of America's Most Powerful and Controversial Vice President," by Stephen F. Hayes, the Weekly Standard writer best known for his effort to bolster the case for a link between al-Qaida and Saddam before the invasion of Iraq and for defending Cheney's pressure on the intelligence community to put its imprimatur on such views.

"I always felt that he was an ally," Hayes quotes an obviously perplexed L. Paul Bremer, who served as the head of the CPA. Bremer ought to have grounds for being confused by Cheney's odd comment. According to his 2005 memoir, "My Year in Iraq," he was first contacted to serve by Scooter Libby and Paul Wolfowitz, the neoconservative deputy secretary of defense. Cheney had already blocked State Department participation in the Office of Reconstruction and Humanitarian Assistance, the CPA's predecessor organization. The CIA had flown Chalabi, a principal source of the false intelligence used to justify the war, later a self-proclaimed "hero in error," from his base in Iran to Iraq with several hundred of his "Free Iraqi Fighting Forces." (Chalabi was long on the payroll of the Iranian intelligence service.) Chalabi and his forces eagerly led the looting of Iraqi ministries. His advice to disband the Iraqi army and fire Baath Party members that ran the government bureaucracies was accepted by Wolfowitz and Feith -- and ratified by Bremer.

In his account, Bremer writes that the Principals Committee meeting of the National Security Council that gave Bremer his marching orders decided that the Iraqi exiles were too weak and unrepresentative to establish authority in the country. Bremer cites his notes from that meeting: "Here's the vice president ... 'We're not at a point where representative Iraqi leaders can come forward. They're still too scared. We need a strategy on the ground for the postwar situation we actually have and not the one we wish we had.' This didn't sound like an open endorsement of the exiles."

Cheney's seeming confession of error is little more than belated historical revisionism to obscure his own part in the fiasco. It is his first step toward walking away from responsibility through self-denial, not least about the reality that the Iranians played him and the neoconservatives as stooges.

Cheney prides himself on his skill as a hidden-hand master manipulator of politics through control of bureaucracies. Hayes' hagiography is a shabby, tendentious work, of the sort that used to be produced in the Soviet Union, impossible to grasp without independent knowledge or access to samizdat. Nonetheless, there are a few shiny objects that can be retrieved from this dump.

Cheney granted Hayes a series of interviews that provide insight into the development of his cynical politics, his view of unaccountable executive power and his penchant for secrecy. One can almost hear Cheney chuckle as he tells his Boswell how the credulous Washington press corps got him wrong all these years, to his everlasting advantage. "The press never looked at my voting record" as a congressman, he says. "They thought I was all warm and fuzzy and they never looked to see."

Cheney also reveals how as President Gerald Ford's chief of staff he learned to undermine and destroy Vice President Nelson Rockefeller, the last unabashed moderate Republican in the White House. Cheney described how he would put "sand in the gears," claiming "we'll staff it out," to kill Rockefeller's projects. Cheney gloats over humiliating Rockefeller at the 1976 Republican Convention, where during Rockefeller's last moment on the public stage, giving the nomination speech for his successor, the microphone suddenly went dead. Cheney recalls that Rockefeller blamed him and that they had "shouting matches." Yet Cheney doesn't deny the accusation. Instead, he snickers. "You've got to watch vice presidents. They're a sinister crowd."

Hayes also recounts Cheney's confrontation with Sen. Patrick Leahy, D-Vt., on the floor of the Senate on June 21, 2004, when, having heard of Leahy's critical comments about Halliburton's contracts in Iraq, he told him, "Go fuck yourself." Hayes quotes a "fishing buddy" of Cheney's, Merritt Benson, recalling that afterward Cheney told him of his regret: "You never, ever let those people get to you. Or then they win." Of course, Cheney was paraphrasing Richard Nixon, the first president he served, who said on the day he resigned his office, "Always remember that others may hate you, but those who hate you don't win unless you hate them. And then you destroy yourself."

But that Nixon citation is not the end of Cheney's reflections on what he calls "the F-bomb." "It was out of character from my standpoint, I suppose," he confesses. "But what can you say ... It was heartfelt." Cheney unleashed is Nixon without regrets. If it feels good, do it -- and it feels so good to drop the bomb.

Shares