The documents disclosed by the DOJ shed very interesting light not only on the process by which the U.S. attorneys were fired, but also on the related conduct of federal law enforcement agencies. One of the claims made by the DOJ as to why it fired Arizona U.S. Attorney Paul Charlton is that Charlton wanted to institute a policy of requiring law enforcement agents to tape record or videotape interrogations and confessions of criminal suspects -- a request which the DOJ refused and, shortly thereafter, fired him.

The documents disclosed by the DOJ with regard to this issue -- here, here, and here (.pdf) -- shed very interesting light on why the DOJ, and the various law enforcement agencies (led by the FBI and the ATF) vehemently oppose having their interrogations recorded.

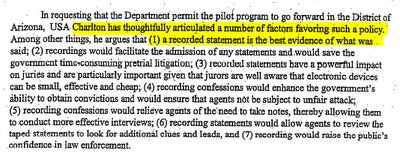

In March, 2006, Charlton sent a letter to Alberto Gonzales' Deputy, Paul McNulty, requesting permission to create a "pilot program" whereby federal law enforcement agencies would be required to tape record interrogations of suspects. This is part of what he wrote:

Charlton cited numerous prosecutions where his office either lost a jury trial or had to accept an inadequate plea bargain because the only incriminating evidence (or confession) was contained in the handwritten notes of FBI agents, which were (either objectively or in the eyes of jurors) unreliable and an insufficient basis on which to convict. He also argued that jurors find it suspicious -- given the frequency with which the Federal Government records everyone (other than itself) and the ease of doing so -- that such interrogations are not taped, and that numerous federal judges have urged federal law enforcement agencies to tape record interrogations and confessions. Charlton therefore wanted all such interrogations and confessions to be recorded.

In a June, 2006 Memo regarding Charlton's request, a Senior Counsel to the Deputy Attorney General summarized Charton's rationale as follows:

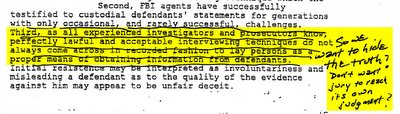

But the Justice Department denied Charlton's request, concluding that it did not want mandatory recording of interrogations and confessions. The DOJ solicited the views of all federal law enforcement agencies -- the FBI, ATF, DEA, U.S. Marshall's Service -- and each of them vigorously opposed mandatory recording. In doing so, one of the principal arguments was that they wanted to conceal from jurors the conduct of law enforcement agents in interrogating defendants and obtaining confessions, because that conduct would appear coercive and improper to jurors.

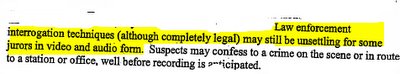

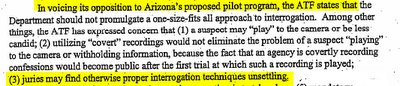

The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms, for instance, cited this argument in a Memorandum it submitted to the DOJ opposing mandatory recordings of confessions and interrogations:

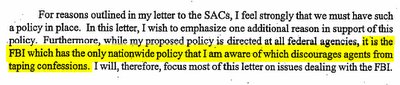

One of the documents disclosed by the DOJ was this extremely interesting letter to the DOJ from the FBI's Office of General Counsel, in which the FBI expressed its opposition as well:

The handwritten reaction (it is unclear who wrote it) reads: "So we want to hide the truth? Don't want jury to reach its own judgment?"

The DOJ memo cited above recommended against Charlton's program, and in doing so, it specifically cited the ATF's concern that jurors would find out what really went on in interrogations and confessions:

This is rather notable for multiple reasons. Initially, the conduct of agents in interrogations would only be at issue where the defendant was claiming that the statements or confessions were coerced -- or otherwise obtained using methods that cast doubt on the reliability of the statements. In such cases, federal agents -- in the absence of a recording -- would still be asked about what they said and what they did in order to prompt the responses or confessions. Thus, even in the absence of a recording, their conduct during the interrogation would be known to the jurors -- unless they lie about what they did and conceal their behavior.

The difference between recording v. no recording is not whether the conduct of federal agents will be an issue in a trial. The difference is whether there will be an accurate or inaccurate record of what these law enforcement agents are doing to extract statements and obtain confessions. Yet here, every federal law enforcement agency is expressly arguing against recordings because they want to conceal from the jury what they did (or because they want to conceal what the defendant actually said).

Jurors, by definition, are randomly selected citizens from the communities in which defendants are tried. If they collectively find behavior of law enforcement agents to be coercive, unconscionable or excessive -- and therefore likely to engender involuntary or unreliable statements and confessions -- that seems to be rather compelling evidence that agents should not be engaged in that behavior.

But this is how our federal government operates now. This whole argument over recordings reflects the prevailing mentality. They engage in conduct that they know is improper and that Americans would find repellent. But their reaction to that knowledge is to figure out how to best conceal what they are doing. That is the argument made by every federal law enforcement agency, and the DOJ, as to why they do not want their behavior recorded. So they continue to engage in all sorts of surveillance and recording of American citizens, yet fight vigorously to ensure that their own conduct is never chronicled.

Shares