It's December 2003. Do you know who the wife of your 2004 Democratic presidential front-runner is?

Dr. Judith Steinberg Dean, M.D., the Vermont internist married to the state's former governor and presidential candidate Howard Dean, has been MIA on her husband's campaign trail, and is bold in her assertion that she will remain almost as absent from his presidency and instead keep up her full-time medical practice.

The quicksilver Dean campaign has already turned water into wine by making his just-folks country doctor act into the hip campaign with momentum. That fizzy, effortless Howard Dean magic may be at work on his wife as well, transforming the abstemious Judith Steinberg -- aka Judy Dean -- into the perfect foil for a new presidential millennium. An unlikely mating of rural career girl, Dr. Quinn Medicine Woman and Donna Reed, Dr. Steinberg could be the anti-Hillary, anti-Laura first lady that Americans have been waiting for: a cipher onto which every woman -- whether she has a high-powered career or is a stay-at-home mom -- can project herself. A woman who, like the rest of her husband's campaign, is almost too good to be true.

The official Dean For America Web site describes the candidate's wife as "the second most important person in the campaign ... [who gives the] insight, advice, and honest feedback that only a life-partner can provide," just after noting that "because of her responsibilities to her patients her time on the campaign trail is limited."

But limited time on a campaign trail doesn't always wash with an American public frantic for demonstrations of familial intimacy from its political candidates. And while Steinberg may provide her husband with many things that only a life partner can, she and every source who spoke for this story have agreed that political counsel is not one of them. Judy Steinberg Dean cares about medicine, not politics, and she shows no signs of shifting her concentration, even for the sake of her husband's bid for the country's highest office.

Steinberg's press for the campaign is funneled through Susan Allen, Gov. Dean's former press secretary, who explained that the good doctor could not speak to Salon because of a particularly grueling hospital schedule. "Setting up an interview means canceling a patient," said Allen, "and she hates to do that."

Eventually, Allen said, Steinberg will "do what Governor Dean asks her to do. If he feels strongly that at some point she needs to make some appearances, I'm sure she will." But until then, the Dean campaign's second most important figure is a woman who quite bluntly refuses to put her husband's career before her own.

"Everything that people thought would not work for Howard Dean has worked for him," said Democratic Party strategist Hank Sheinkopf, who worked on the Clinton-Gore 1996 media team. "Being from a small state, being a physician, concentrating on youth, commandeering the Internet, and having a wife who is a nonparticipant. These are nontraditional ways of looking at a presidential campaign, and they are working."

Steinberg's insistence on being the anti-political wife echoes Dean's role as the anti-politician. Through her husband's 12-year stint as governor of Vermont and now through the first giddy months of his presidential bid, she has been a stethoscope-wielding Bartleby. She prefers not to: Not to get dolled up, not to do a lot of press, not to talk about her family, not to sacrifice her professional identity for her husband's, not to open her home to the beady-eyed lifestyle press.

"Vermonters were always very respectful of her choice not to be a public figure," said Allen. "It's been [the Deans'] pattern and it's worked for them." She paused for a moment before chuckling and saying, "This is a little different, obviously."

Kathy Hoyt, Gov. Dean's chief of staff from 1991 to 1997 and one of the surrogates commissioned by Allen to speak about Steinberg, recalled seeing her at state functions in Montpelier only a handful of times. "In Vermont it was an accepted thing that she wasn't involved in a lot of events," said Hoyt. "She'd come to the inaugurations, and I know she came to the swearing-in the first time and I think the other times he won reelection, but I'm not sure."

"I know everyone is very skeptical about whether she can really pull off a whole different way of doing this," Hoyt continued. "But I admire her for trying."

"On the one hand, Democratic primary voters may actually look positively on the fact that she has not been involved in her husband's campaign and has this important and demanding job," said Howard Wolfson, former press secretary for Hillary Clinton's New York Senate campaign. "On the other hand, I do think that there are many voters in this country who like to have a sense of who their president is, what their family is like, what their spouse is like."

So far, details about Judy Dean have been scarce and spoon-fed to the public in the form of a few well-placed newspaper interviews with decidedly sympathetic journalists. In October, she was profiled by syndicated columnist Ellen Goodman of the Boston Globe, and in August she sat down with both Newsweek's Eleanor Clift and Johanna Neuman of the Los Angeles Times.

Allen confirmed that while there is "no organized pattern for doing one [interview] over another," that Steinberg knew Goodman, and Dean knew Clift, making those interviews more comfortable first dips into the media waters.

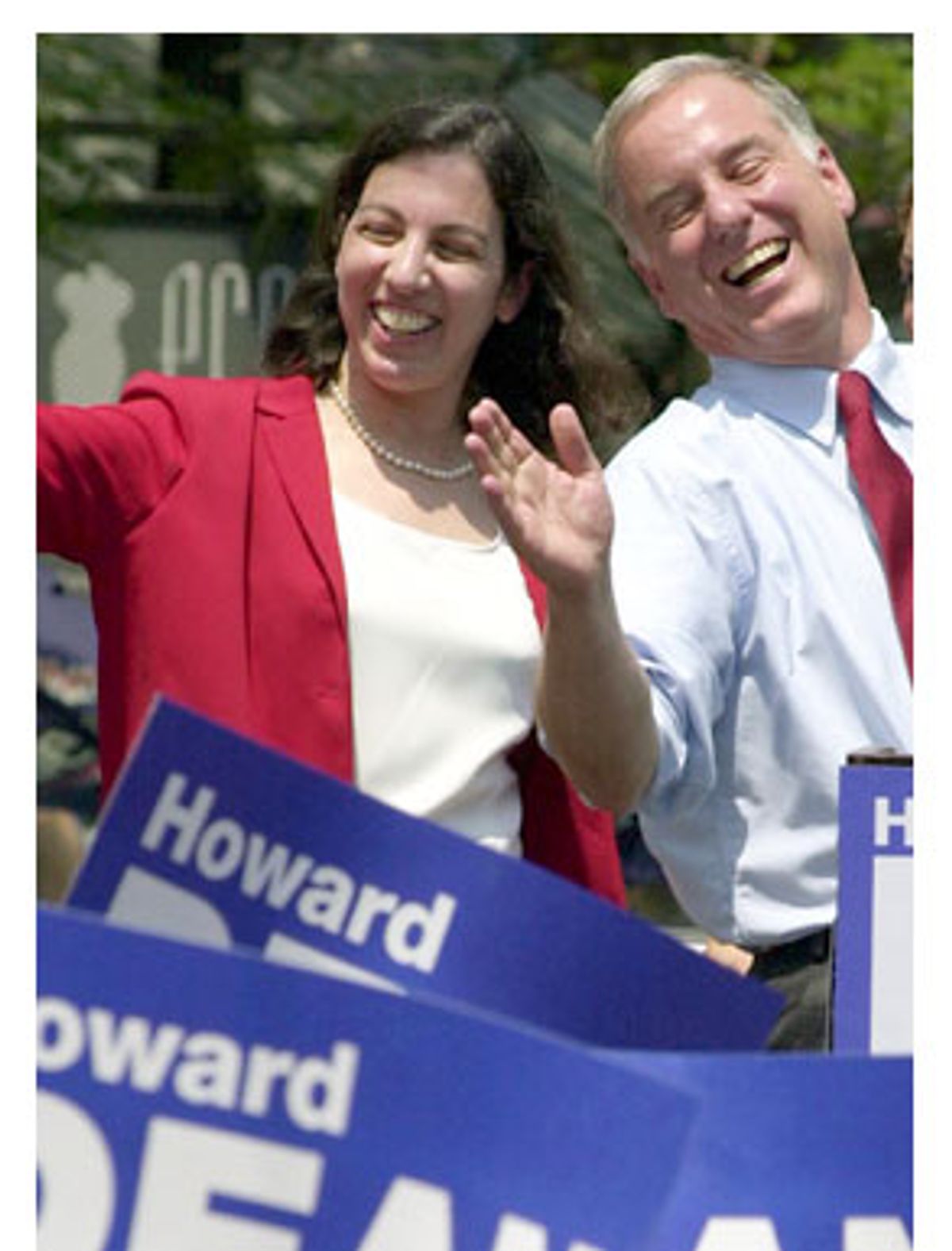

The bits of information revealed in these profiles are precious: Judy Steinberg Dean canoes and hikes and rides her clunky old bike around Lake Champlain. She has only bought one new suit -- a red one! -- for her husband's presidential campaign. She doesn't watch the debates on TV because her family doesn't have cable. She makes house calls and her office in Shelburne, Vt., is full of mismatched furniture.

Steinberg told Goodman that she values the tiny size of her practice because, "If six patients call me with shortness of breath, I can tell which one needs to go to the emergency room and which one doesn't."

Well, shoot, that's enough down-home earnestness to make voters short of breath. (And yes, everyone who has written about Steinberg has compared her to Stockard Channing's ballsy first lady and working physician Abigail Bartlett on the left's wet dream, "The West Wing.")

Judith Steinberg was born in 1953 and raised with three sisters in one of Long Island's ur-suburbs, Roslyn. Both her parents were doctors, and the family was Jewish. Steinberg studied biochemistry at Princeton, and medicine at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx, where she encountered Park-Avenue-reared Howard Dean. Their meet-cute story involves doing covert crossword puzzles in the back of neuroanatomy class.

David Wolk, the president of Castleton State College and Dean's former commissioner of education, said that he and his wife are longtime family friends of the Deans. He described them as a loving, affectionate couple who do not socialize much. "She is a solid, bright person who has given him the anchor and balance he's needed. I know because I've witnessed it when she speaks to him with unbridled candor, and believe me, he needs that ... She keeps him honest, keeps him on track, tries not to let him get too big for his britches."

After their 1981 marriage, Steinberg set a precedent for doing her own damn thing by completing a fellowship in hematology at McGill University in Montreal while her husband set up his medical practice just outside of Burlington in Shelburne. She later joined him and became his partner in the practice as he began to dabble in local politics. When Dean became governor in 1991, Steinberg and another doctor absorbed his patient load.

"For a long time I don't think they had a TV at home," said Wolk, who observed that the couple rarely dines out, and that the Deans' limited social life centers around their children, Yale sophomore Ann, a serious ice hockey player who worked on her father's campaign this summer, and high school senior Paul, whom Wolk said is first in his class at Burlington High School, and is "even more detached" from his father's political life than his mother.

Wolk's two daughters, a senior and a sophomore at the University of Vermont, are Steinberg patients, and he said, "they tell me that she's got a very warm bedside manner and gives them no-nonsense advice. What you've got in Judy is this incredible native intelligence," he said.

Garrison Nelson, a University of Vermont political science professor whose forthcoming book is about presidential politics in New England, has been one of Dean's most irritating critics. In November, Dean told the Boston Globe that Nelson has "made a career out of trashing" him. But when called for this story, Nelson said, "Judy is a fabulous doctor. I hear this from her patients. Howard was a good doctor but not in Judy's class. Many of her patients are scared he's going to win and that she's going to leave town."

While Steinberg's unbreachable devotion to her career is an attitude that will surely resonate with feminists and professional women, there is the faintest whiff of family values in her desire to stay at home rather than hit the campaign trail. It's that whiff that might make her appeal to the people Hank Sheinkopf calls the "Nascar men, this election's swing voters, who care about family."

"'I don't give advice,'" Goodman quotes Steinberg as saying. Goodman continues, "What she does is practice medicine and run a home." Clift described the family dynamic this way: "When [Dean]'s home from the campaign trail, they don't talk politics, they talk about their two kids."

"Judy hates politics! Hates it!" said Nelson. "She is just not interested."

Steinberg herself could have been reciting part of the 1953 Wellesley College "marriage lectures" featured in the upcoming "Mona Lisa Smile" when she told Clift, "We took a long walk and we discussed should he run. I thought my role was basically to say, 'Yes, the family could handle this. Go ahead if this is what you think you should do.' I certainly wasn't giving him advice about whether he should do that or not. He was asking, 'Would it be OK for the family?'"

It's clear that Steinberg's lack of interest in political life is more about having better things to worry about than it is about deferring to her man. But it might just play as the spoonful of traditionalist sugar that could make the idea of a Jewish scientist first lady who refuses to abandon her career go down a little easier in middle America.

Still, Steinberg's claim -- that should her husband win the election, she wouldn't stop practicing medicine, nor would she travel very much or play host to foreign dignitaries -- strikes some as pretty unrealistic, if not naive.

"All good intentions aside, I don't think she would really be able to continue working as a doctor if she became first lady," said presidential historian and first-lady biographer Carl Anthony, who said that he's in the midst of working on a dramatic television character who is a potential first lady who's made the same choices as Steinberg. "Can you imagine the Secret Service in a hospital, checking out every ambulance that pulled up, every person in the waiting room? It could be a little bit of a difficulty."

Anthony noted that the last first lady who actually abstained from traditional duties was the bright but tubercular Eliza Johnson, wife of Andrew Johnson.

Whether or not Steinberg's intentions could ever be converted into professional reality, the fact that she has voiced them has already gotten her noticed.

"I think we are at a place where we in this country understand that women work outside of the home. And that it would in fact make sense for a first lady to have a job of her own that was separate and apart from her husband's," said Wolfson, who added that "it may well be a selling point." But, he continued, "it is a separate question whether or not Ms. Steinberg -- Dr. Steinberg -- can go through a campaign without campaigning."

Sheinkopf agreed: "Keeping her medical practice is a good thing. Not participating in the campaign is not such a good thing," he said, in reference to the ways in which a voting public needs to warm to its candidates. He maintained that regardless of her desires, Steinberg cannot stay hidden forever. "After the Clintons, is the press corps going to let her get away with being a non-person? I wouldn't hock the house on that one."

Steinberg's spokesperson, Susan Allen, says that Steinberg will put down her tongue depressor and join her husband on the stump soon.

"She will do television. She understands she needs to do television," she said, confirming that there is a list of network journalists already lined up to sit down with Steinberg.

The Deans have said that they are invested in protecting their children's privacy, and that may be one of the reasons that Steinberg has shied away from doing a lot of press. Paul's brush with the law this summer -- he got caught driving the getaway car for four of his friends who were stealing alcohol from a local country club -- was one of the only incidents that has brought Steinberg into the public eye so far. She accompanied him to the Burlington police station, and later appeared with him and Dean in court. (Paul Dean was sentenced to a court diversion program along with his friends.)

Once Steinberg does become more visible, the question of her religion is sure to be raised, just as it was with Joe and Hadassah Lieberman in the 2000 election. But what impact it will have on voters -- if any -- is debatable. Though Howard Dean was born a Catholic, raised Episcopalian, and became a Congregationalist, he has said that his two children "consider themselves" Jewish and celebrate Jewish holidays. Asked whether a religiously divided family would have an impact on voters, Sheinkopf said, "I don't think it matters that much. He's not running for pope. In a post-Kennedy Catholicism era, voters tend to be pretty reasonable about religion."

Those voters who do take issue with an interfaith couple likely won't be voting for Howard Dean anyway. And in certain places, Steinberg's background is certain to be a draw. "As they get to New York, it makes a lot of sense to showcase her," Sheinkopf said. "She's not just Jewish but a professional woman, which will be helpful."

Carl Anthony says that this early in the election cycle a candidate's family usually doesn't play such an important role. "You're going to start seeing a lot of that [family reporting] when Newsweek and Time and People do their cover stories, like, 'Judy Dean: Is There a Doctor in the House?'" he said. "But you've got to remember that we didn't know that Chelsea Clinton even really existed until a week before the Democratic Convention in 1992. Once it seems like someone's definitely going to get the nomination, that's when you'll see Judy Dean's recipe for challah bread somewhere."

Nelson disagreed. "She is a private person dedicated to her patients and her practice and when Good Housekeeping calls for her Christmas cookie recipe I don't think she's going to play along. I mean, Hillary rose to the challenge. But I don't think Judy will."

The truth, though, is that with or without baking tips, the supposedly recalcitrant Deans are way ahead of the game. In September, Steinberg actually sent a campaign-fundraising letter on behalf of her husband, the first three paragraphs of which were devoted to explaining why she would not be campaigning with him.

"This letter is my first public campaign activity for my husband, Howard Dean," the letter began. "I am a doctor, not a politician, and Howard to his great credit has never expected me to campaign for him. As a doctor and a partner in a medical practice, I have a responsibility to my patients. That's why my time 'on the campaign trail' is limited."

This earnest expression of "No campaigning please, I'm helping sick people," was brilliant -- and subtle -- political posturing.

In many ways, Hillary Clinton, who was listed as one of the country's top 100 attorneys before her husband became president, is the most obvious corollary to Steinberg. But in fact, what the Steinberg-Deans may provide is an antidote to the um ... intimacy of the Clinton administration.

The Clinton marriage was a spectacle from Day 1, which could be traced to their joint appearance on "60 Minutes" in which they did damage control on the Gennifer Flowers situation and admitted to having had bumps in their marital road. Hillary gave up her law practice, instead fulfilling the couple's two-for-one campaign promise and attempting to reform healthcare. It didn't go very well.

"What Hillary Clinton has always said [of being first lady] is that this is a role not a job," said Wolfson. "Everybody remakes it in a certain way."

The one thing the Clintons always got right was the handling of their daughter Chelsea. Even a vast right-wing conspiracy could not assail the grace with which they kept their adolescent offspring's life private; and the press, which has gleefully ripped apart everyone from Patti Davis to Amy Carter to the Bush twins, kept a respectful distance.

It's as if the Deans have taken the protective bubble that was fitted for Chelsea and wrapped it around their entire New England home, sending only the patriarch out into the biting world of media and high-stakes campaigning.

"We may be at a place in this country where people feel like we've kind of gone too far in the boxers or briefs direction," said Wolfson. "The Dean campaign is obviously betting that we have."

Shares