The headline could be "The Wise Men Strike Back" or maybe "The Wise Men Strike Out."

Wednesday's press conference unveiling the report of the Baker-Hamilton commission was as close as Washington comes to a Rorschach test. Depending on perspective, this was the moment when the foreign-policy establishment scathingly repudiated George W. Bush's conduct of the war, or proved its own irrelevance by singing a hymn to bipartisanship unlikely to be heeded by anyone in the White House bunker.

A day after Robert Gates -- who left the panel after he was nominated to replace Donald Rumsfeld at the Pentagon -- admitted we were not winning the war, the Iraq Study Group upped the ante by beginning its report with this soon-to-be-famous appraisal, "The situation in Iraq is grave and deteriorating." But the 10-member bipartisan committee also went out of its way to congratulate its own even-handed fair-mindedness, even as former Wyoming Republican Sen. Alan Simpson railed against what he called "the 100-percenters" -- ideological warriors whom he described as people who are "not seekers, they're seethers." In an earthy counterpart to the high-minded tenor of the proceedings, Simpson also claimed that these zealots of the left and right "have gas, ulcers, heart-burn and B.O."

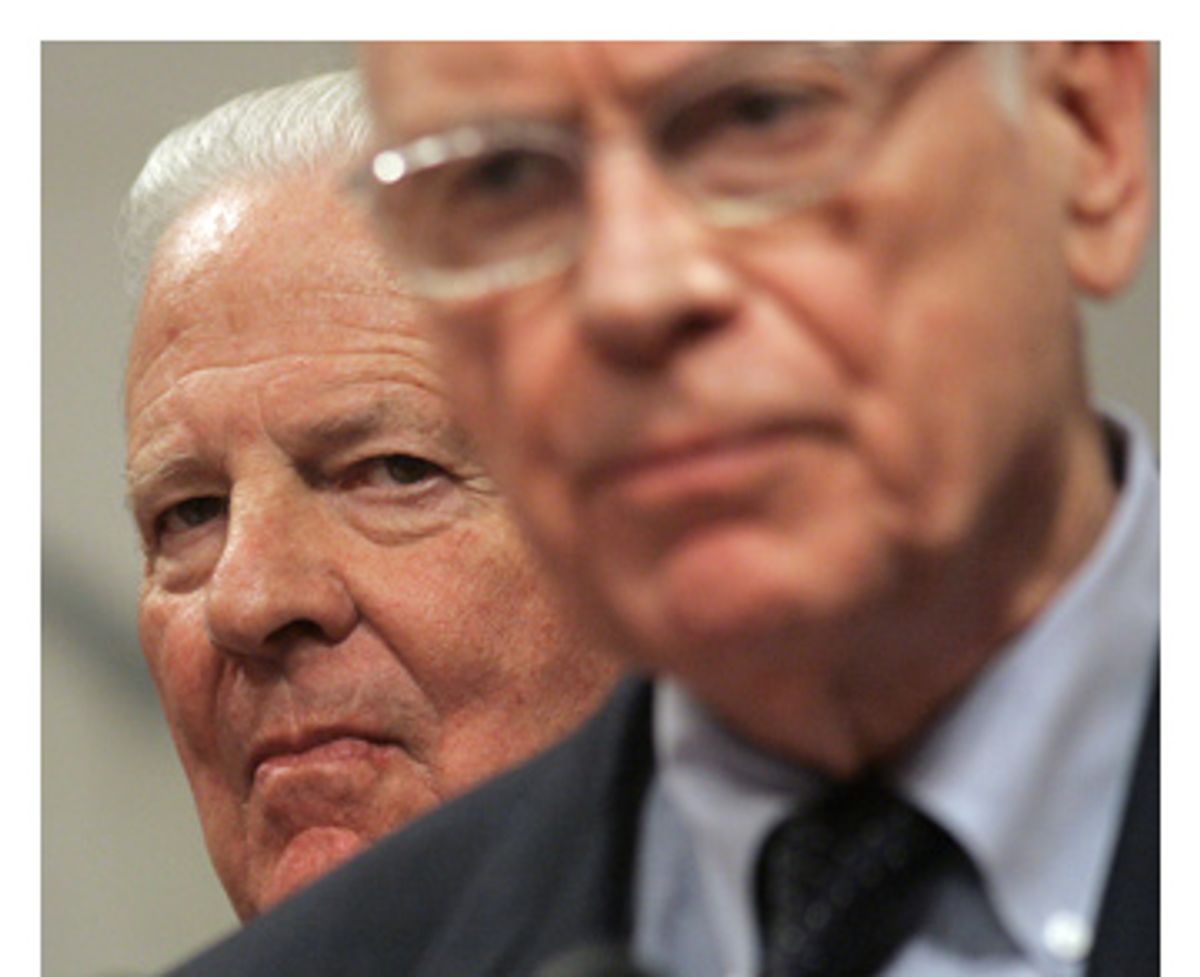

Bush family consigliere James Baker, who chaired the group along with Democrat Lee Hamilton, artfully tap-danced away from any direct criticism of the president. The most hard-hitting recommendations were read aloud by Hamilton, such as the one calling for "a change in the primary mission of U.S. forces that will enable the United States to begin to move its combat forces out of Iraq responsibly." Asked specifically about the president's reaction to the report, Baker, with a smug smile, immediately turned the microphone over to former Clinton chief of staff Leon Panetta, who piously declared, "This country cannot be at war and be as divided as we are today. You've got to unify the country."

The significance of the Iraq Study Group has little to do with its actual recommendations, which Baker admitted were not a "magic formula that will solve the problems of Iraq." Rather its importance rests entirely with the luster of the former officials on the commission, including two secretaries of state (Baker and Lawrence Eagleburger), a secretary of defense (William Perry), an attorney general (Ed Meese) and its only woman, retired Supreme Court justice Sandra Day O'Connor. Baker jokingly described them as "a group of has-beens" -- but the reality is this is about as blue-ribbon an assemblage as you get in contemporary America aside, perhaps, from the front row at a state funeral.

But it may not be enough to convince Bush to accept the abject failure of his Iraqi adventure -- a message the president has not heeded when it was delivered by press reports, retired generals, think-tank studies, opinion polls and the results of the 2006 congressional elections. The short-term issue is not what Bush says publicly, since rewriting presidential rhetoric on Iraq requires the talents of both a George Orwell and a Lewis Carroll. (White House press secretary Tony Snow seems to be channeling Humpty Dumpty's dictum: "When I use a word, it means just what I choose it to mean -- neither more nor less.")

What is at stake is a change of policy that is more than cosmetic. The report is unambiguous about calling for a prompt pull-back: "By the first quarter of 2008, subject to unexpected developments in the security situation on the ground, all combat brigades not necessary for force protection could be out of Iraq." While the Iraq Study Group's commitment to beef up American training of the Iraqi army may prove as foolhardy as Richard Nixon's faith in "Vietnamization," the report does offer the murky outlines of an eventual road home from Baghdad.

After the press conference ended and the TV lights died down, the 76-year-old Eagleburger, who travels by wheelchair these days, stayed behind to chat with reporters. Asked whether the president would give the report a fair look, Eagleburger immediately replied "yes," and then paused to give a long sigh. "I don't know what a 'fair look' means, but he'll certainly consider it."

The bet here is that more truth was embedded in Eagleburger's sigh then in all of Wednesday's brave words about a new "way forward" in Iraq and a new era of bipartisanship in Washington.

The collapse of Bush's stay-the-course political constituency, dreaming of victory in Iraq, has happened too quickly to imagine the beleaguered president abruptly reversing direction. The arrival in the Cabinet of Gates, who was confirmed by the Senate Wednesday afternoon, plus the military's own upcoming strategic reassessment, guarantees endless rounds of meetings debating the obvious. At a time when the president stubbornly refuses to negotiate with Iran and Syria, the report calls for a "new diplomatic offensive," including all nations in the region, which "should be launched before December 31, 2006." Somehow it seems unlikely that Bush will spend New Year's Eve brooding over whether to call Tehran and Damascus because of the Iraq Study Group's deadline.

While public opinion was most tellingly revealed in the congressional elections, it will be intriguing to see what happens with the polls after voters have time to digest the Iraq Study Group's report. Up to now, about the only belief that unifies the electorate is a distaste for the decision to invade Iraq. Pollster Andrew Kohut, the president of the Pew Research Center, underscored this point when he said last week in an interview, "You're not going to get a sense from public-opinion polls what course to take in Iraq. There is no consensus. This is an issue on which the public is looking for leadership."

The 79 recommendations (the odd-numbered precision comically echoed a magazine cover promising "79 new sexual tricks") of the Iraq Study Group are unlikely to inspire a mass movement, although Vintage has published the report in book form. After all, this is a commission that explicitly repudiates "a precipitate withdrawal of troops and support" as fervently as it rejects "staying the course" and sending more troops to Iraq. For those like John McCain and Silvestre Reyes, the incoming Democratic chairman of the House Intelligence Committee, who believe that more combat brigades are a realistic solution, the report offers a blunt response. It quotes an unnamed American general saying that unless the political morass is somehow remedied in Baghdad, "all the troops in the world will not provide security."

Despite the Iraq Study Group's infatuation with bipartisanship, the most potent pressure group in the Iraq debate remains the Republican Party. Up to now, only mavericks like Nebraska Sen. Chuck Hagel have loudly dissented from the official White House line that this war is worth fighting and can still be won. But privately Republicans recognize the dire political consequences for their party in 2008 if Bush does not quickly embrace realism in Iraq. The new crop of GOP congressional leaders (Mitch McConnell in the Senate and John Boehner in the House), worried about being permanently relegated to the minority, may prove to have more clout with the White House than the foreign-policy titans of yesteryear.

The Baker commission's lasting contribution may be simply changing the tenor of the debilitating debate in Washington. No longer is it just the liberal media or Democratic defeatists who harp on the bad news from Iraq. Now the bipartisan establishment (including Meese, the original Reaganite) has put its imprimatur on the doctrine that victory is out of the question in Iraq. What remains -- and achieving it will try the talents of White House spinmasters, military strategists and foreign-policy theorists for at least the next year -- is to arrange the terms for America's eventual retreat from the humiliating and tragic blunder that was the Iraq War.

Shares