Short of "traitor," "appeaser" is the dirtiest word you can call an American politician. And ever since 9/11, supporters of George W. Bush's Middle East policies have promiscuously used both words to smear their opponents. In the immediate aftermath of the attacks, prominent blogger Andrew Sullivan attacked Bush critics as "the enemy within the West itself -- a paralyzing, pseudo-clever, morally nihilist fifth column." Neoconservative publications like the Weekly Standard compare antiwar leftists to Neville Chamberlain so often they should give out free umbrellas with every issue. And the right-wing blogosphere is pretty much one endless shriek of "treasonous liberals!"

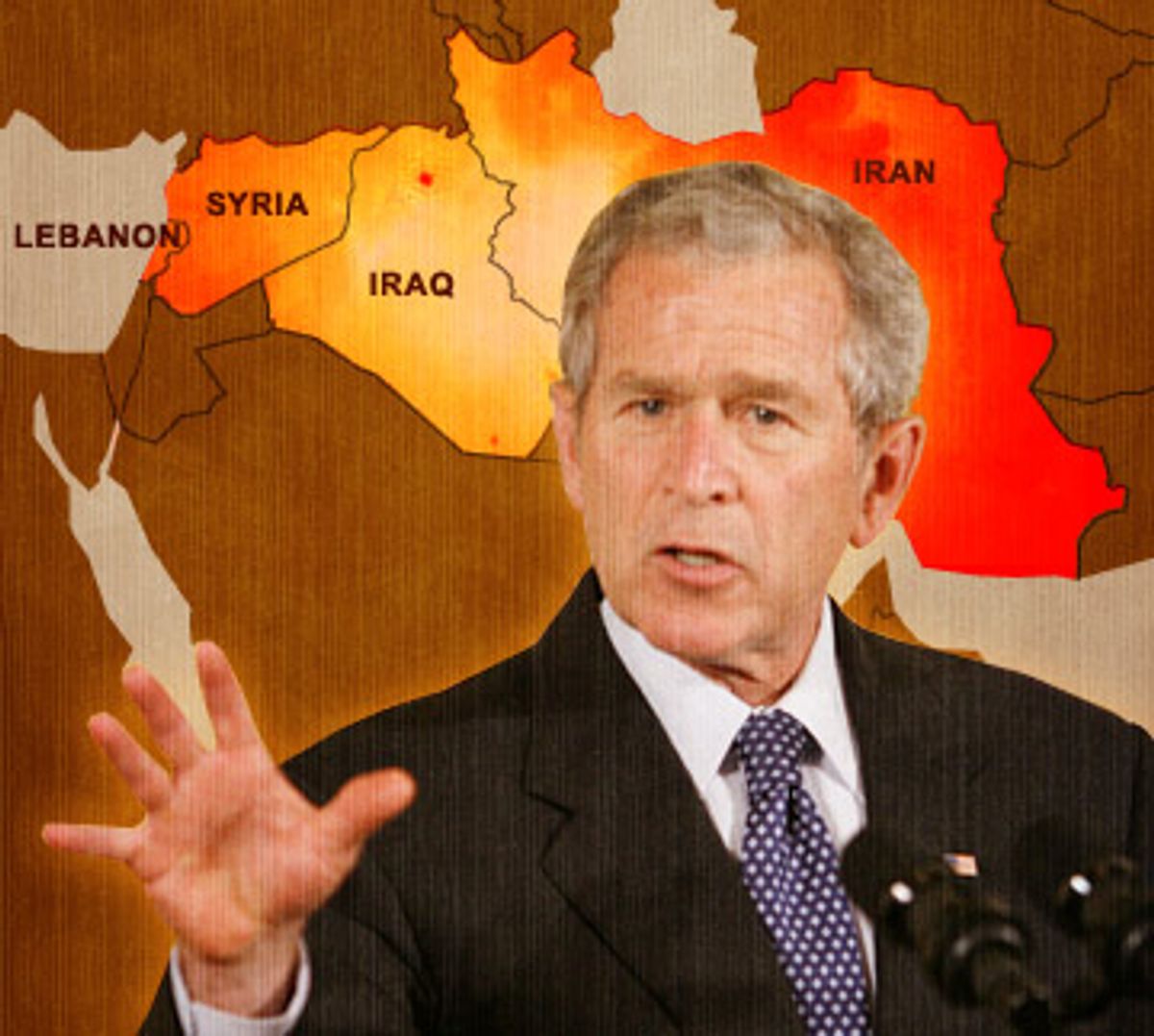

One might think that the colossal failure of Bush's "shoot first, think later" approach to the Middle East would have put to rest the accusations of appeasement and betrayal. But with a few exceptions (Sullivan, to his credit, has recanted), it hasn't. Presumptive GOP presidential nominee John McCain has repeatedly accused Barack Obama of being weak, naive and willing to sell out America to the "terrorists." On his recent trip to Israel, Bush compared those who support negotiating with "terrorists and radicals" to Nazi appeasers. Although Bush denied it, his remarks were obviously aimed at Obama.

But the chest beating, the contempt for "naiveté" and the fetishization of "toughness" are not limited to the right. The Democratic Party abandoned its post before the Iraq war precisely because it was afraid of being smeared as "soft on terrorism," and the party has still not unequivocally rejected Bush's policies. The exemplar of mainstream Democratic Party thinking is Hillary Clinton, who supported Bush's Iraq war resolution, voted for the Kyl-Lieberman Amendment that declared Iran's Revolutionary Guards a "terrorist organization," and called Obama "irresponsible and naive" for saying he would be willing to meet unconditionally with the leaders of Iran, Syria, North Korea and Cuba.

Clinton is no Bush, and she probably adopted some of these right-leaning positions both because she felt as a woman she had to exaggerate her toughness, and because later she decided that the best way to attack Obama was from the right. But even though those decisions, particularly the Iraq war vote, doomed her campaign, she has still not completely repudiated Bush's tough-guy approach, and her cautious centrism on the Middle East remains the party's default position.

Of the major presidential candidates, only Obama has dared to unequivocally reject the Appeasement Paradigm. He has vowed to end not only the Iraq war but, crucially, also what he called "the mind-set that got us into war in the first place."

The coming election is shaping up to be a referendum not just on Iraq but on that black-and-white mind-set. McCain and the GOP will relentlessly attack Obama as weak, inexperienced and cowardly, pointing to his willingness to talk to our enemies as evidence. But the fact is that what Obama is proposing is simply rational, realistic foreign policy. And the proof is that the rest of the world, including Israel, has defied the Bush administration and is talking to the "terrorists."

If it's appeasement to talk to "evildoers," we are all appeasers now. Everywhere you look, our allies -- or we ourselves -- are negotiating with members of the "Axis of Evil" and their allies.

Israel, whose U.S.-backed security theoretically could be most directly compromised by "appeasement," has been talking to the Palestinian militant group Hamas, using Egypt as an intermediary. Israel isn't doing this because it suddenly decided that "some ingenious argument will persuade [Hamas] they have been wrong all along," as Bush derisively commented in his thinly veiled attack on Obama, but because it is trying to reach agreements on issues critical to its security, including a cease-fire, prisoner exchanges and border-crossing arrangements. Israel has realized that pretending that Hamas does not exist, or wishing it would disappear, is not a viable strategy.

Similarly, the Jewish state is engaged in negotiations over prisoner exchanges with another bitter enemy, Hezbollah, using Germany as a go-between. Of course, these talks aren't aimed at producing a lasting peace; they're extremely limited in scope. But the very fact that they're taking place reveals the absurdity of the Bush administration's attempt to impose a total blockade on its enemies.

Still more embarrassingly for the appeasement crowd, Israel is talking with its old foe Syria, using Turkey's good offices. No one dreams that Israel has suddenly joined the Basher Assad fan club; its goal is to split Syria off from Iran, and if the price for doing that is ending its 40-year occupation of the Golan Heights, that's a price it deems worth paying. The U.S., which has opposed any diplomatic openings to the nation it regards as a junior member of the Axis of Evil, thus finds itself in the ridiculous position of being ignored by the very country its boycott was intended to protect. There couldn't be a clearer example of the way that moralistic posturing dissolves when confronted with facts on the ground.

In fact, the U.S. itself should have learned that lesson in Iraq. Just a couple of years ago, the Bush administration portrayed Sunni insurgents who were killing U.S. troops as evil terrorists. But then U.S. commanders realized that those disaffected Sunnis could play a key role in fighting al-Qaida, and suddenly the "terrorists" were magically transformed into peace-loving "Sons of Iraq."

As for the ultimate boogeyman, Iran, the U.S. has conducted talks with it as well, albeit extremely limited ones.

All this means that Obama's supposedly "weak" and "risky" approach simply follows one that the interested parties in the region are already engaged in. All across the Middle East, the Bush administration's simplistic insistence on isolating the bad guys is breaking down. It's Foreign Policy Realism 101. Any serious student of the Middle East, indeed of any intractable crisis, knows it's essential to talk not just to your friends, but to your enemies. This doesn't mean you like them or support them: It just means you recognize when it's in your interest to deal with them. But when it comes to the Middle East, this is apparently too complex a truth for U.S. pundits and politicians to swallow. They continue to repeat conventional condemnations of "terrorists and radicals" even when events make that moralistic stance meaningless.

A recent column by New York Times columnist David Brooks about Hezbollah offers a perfect example. It was a peculiar column. Although he ended by comparing, with apparent approval, Obama's foreign policy approach to Bush the elder's, Brooks first found it necessary to take Obama to the woodshed for his suspiciously nuanced attitude toward the Lebanese militant group. Brooks opened by flatly declaring "Hezbollah is one of the world's most radical terrorist organizations" -- one of those question-begging definitions that forecloses all discussion. He cited Obama's call for diplomatic efforts to build a "new Lebanese consensus" as having "the whiff of what President Bush described yesterday as appeasement." And he went on to write, "Does Obama believe that even the most intractable enemies can be pacified with diplomacy? What 'Lebanese consensus' can Hezbollah possibly be a part of?"

A week after Brooks wrote his column, Lebanon signed the Doha agreement, which was a decisive victory for Hezbollah and its allies. It gave Hezbollah veto power over cabinet decisions, deferred demands that the organization disarm and acknowledged that the militant group is a key political player in the country. Army chief Michel Suleiman, named president, proceeded to deliver a speech in which he spoke respectfully of Hezbollah as "the resistance," finessed the question of disarming it and called Israel "the enemy." The country celebrated the agreement rapturously.

Of course, the nation's reaction to Doha doesn't mean that all Lebanese support Hezbollah: Many detest it. The nation is fragmented on political and sectarian lines, and the possibility of another civil war still looms. Hezbollah is not part of a "Lebanese consensus" because there is no Lebanese consensus. But as Doha confirmed, the militant group is an integral part of Lebanon's reality. And Lebanon's task now is to find a way to move toward that consensus -- one that must include Hezbollah.

So according to Brooks, a conservative, but one who on this subject speaks for virtually the entire American political and media establishment, it is forbidden for Obama to support what the Lebanese themselves are trying to do. If Hezbollah is beyond the pale, then no one must deal with it. If reality does not conform to ideology, then reality must be denied.

The U.S. faces a crucial choice in Lebanon, a tiny nation that in many ways is a microcosm of the entire Middle East. It can put its head in the sand, denounce Hezbollah, and try to destroy it -- the approach followed with such ringing success by the Bush administration. Or it can recognize that, despite the conventional wisdom served up by pundits like Brooks, sometimes even the most intractable enemies canbe pacified with diplomacy.

In the Middle East, everything is interrelated. That's why successful diplomacy in one arena can have beneficial effects in another -- and why the Bush administration's refusal to talk to its enemies was so fatally flawed. As Rami Khouri, editor at large of the Beirut-based Daily Star newspaper, pointed out in a perceptive recent column, the key issue facing Lebanon is the "Hezbollah-state relationship, which is directly or indirectly linked to other tough issues such as Syrian- Lebanese ties, and the role of external powers such as Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the United States."

The U.S. can play a constructive role in Lebanon, and nudge Hezbollah toward giving up its arms and joining the Lebanese polity, in a number of ways. A resolution of the Israeli-Palestinian crisis would go a long way toward depriving Hezbollah, whose prestige and power rest on its appeal to pan-Arabism and its support for the Palestinians as well as the social services it provides, of its increasingly shaky raison d'être. And a grand bargain between the U.S. and Iran could result in the mullahs' pulling the plug on their client. (In fact, Iran made a secret offer back in 2003 to do just that in exchange for normalized relations with the U.S., but the Bush administration refused.)

No one knows whether Obama's advocacy of a more muscular diplomacy (an approach that, as he told Brooks, does not rule out force) will translate into such foreign-policy successes. But more than five years after the U.S. invaded Iraq, it should be clear that the ignorant, black-and-white approach pursued by the Bush administration has been extremely harmful to our national interests. Accusations of "appeasement" and denunciations of "terrorists and radicals" may provide visceral satisfaction, but they are no basis for a realistic foreign policy. Until America musters the courage and wisdom to look reality in the face, we will continue to lose in every conceivable way in the Middle East.

Shares