I don't know what the rating was for last night's All-Star Game in Seattle, but it was lower than it was the year before, just as it has been lower nearly every year for the past 10 years. The ratings for All-Star games in general have plummeted dramatically since the early '90s, to a point where the NBA All-Star Game drew just a 5.1 share this season (lowest since the dark days before Magic Johnson and Larry Bird came on the scene), the NFL Pro Bowl just 4.7 (Is football the stupidest sport in which to have an all-star game?) and the NHL a truly ridiculous 1.7 (each point indicates about 1.2 million households). By this standard, baseball's game is doing fairly well at 10.1 last year, but there's no doubting the message of the overall trend.

Football can do nothing to revamp its package (Who cares when the season is over?), and nobody can get an NBA player to play defense on a holiday, so those games are probably doomed. Baseball could do some things to boost interest, but nobody wants to deal with the political consequences. For instance, the number of players. When I was growing up you could watch the All-Star Game and stand a reasonably good chance of seeing some really interesting matchup at least twice -- Willie Mays vs. Whitey Ford, Juan Marichal vs. Tony Oliva, like that. There were so few teams that you knew all the players, and many of the stars played the whole game. Now, with 30 teams and at least one player from every team included -- a really dumb rule -- players are shuffled in and out so fast that the game never really gets any rhythm going.

The cure for this is obvious: Reduce the number of players to 24, the number on a Major League roster. And since pitchers hate going to the All-Star Game anyway, limit the selection of pitchers to, say, five. The problem is that Major League Baseball isn't willing to put up with all the whining and howling from the press, fans and players about the guy who didn't get to go.

This illustrates a great truth about All-Star Games that we tend to forget every year when the ratings are announced, namely that there's as much interest in the All-Star selection as there is in actually watching the game. Fans love arguing about who's best; after all, your favorite player might have a bad night in a real game, but in your arguments he's always going to be a winner.

But the quality of the debating has gone downhill in recent years. In times past there was no need to define "All-Star"; there might be some debate about whether Roberto Clemente should start ahead of Hank Aaron or whether Juan Marichal was better than Bob Gibson, but nobody dared to argue that Hugo Throckmorton, a 12-year veteran with a .257 average and a fantastic first half of the season, should be starting in place of a slumping Willie Mays. These days, the Hugo Throckmortons not only get the votes, but there isn't much of a debate. The selection of the Seattle Mariners' Bret Boone as the American League second baseman is a perfect case in point. Over the previous decade the Cleveland Indians' Roberto Alomar has clearly established himself as an All-Star, hitting over .300 eight times, scoring more than 100 runs five times, stealing over 400 bases and winning a pile of Gold Gloves. In that same time span, Bret Boone has clearly demonstrated that he is not an All-Star, batting .255. Now, this season, because he hit a few home runs and has been fortunate enough to bat cleanup in a lineup where everyone reaches base, Boone is leading the league in RBIs. Now, does anyone really think Bret Boone has suddenly developed into a great player? Of course not; open a baseball encyclopedia to the phrase "One-Year Wonder" next year and you'll see Boone's picture. So why is he starting on the All-Star team ahead of Alomar, who may be the best second baseman in American League history (and who is currently leading the league in batting)?

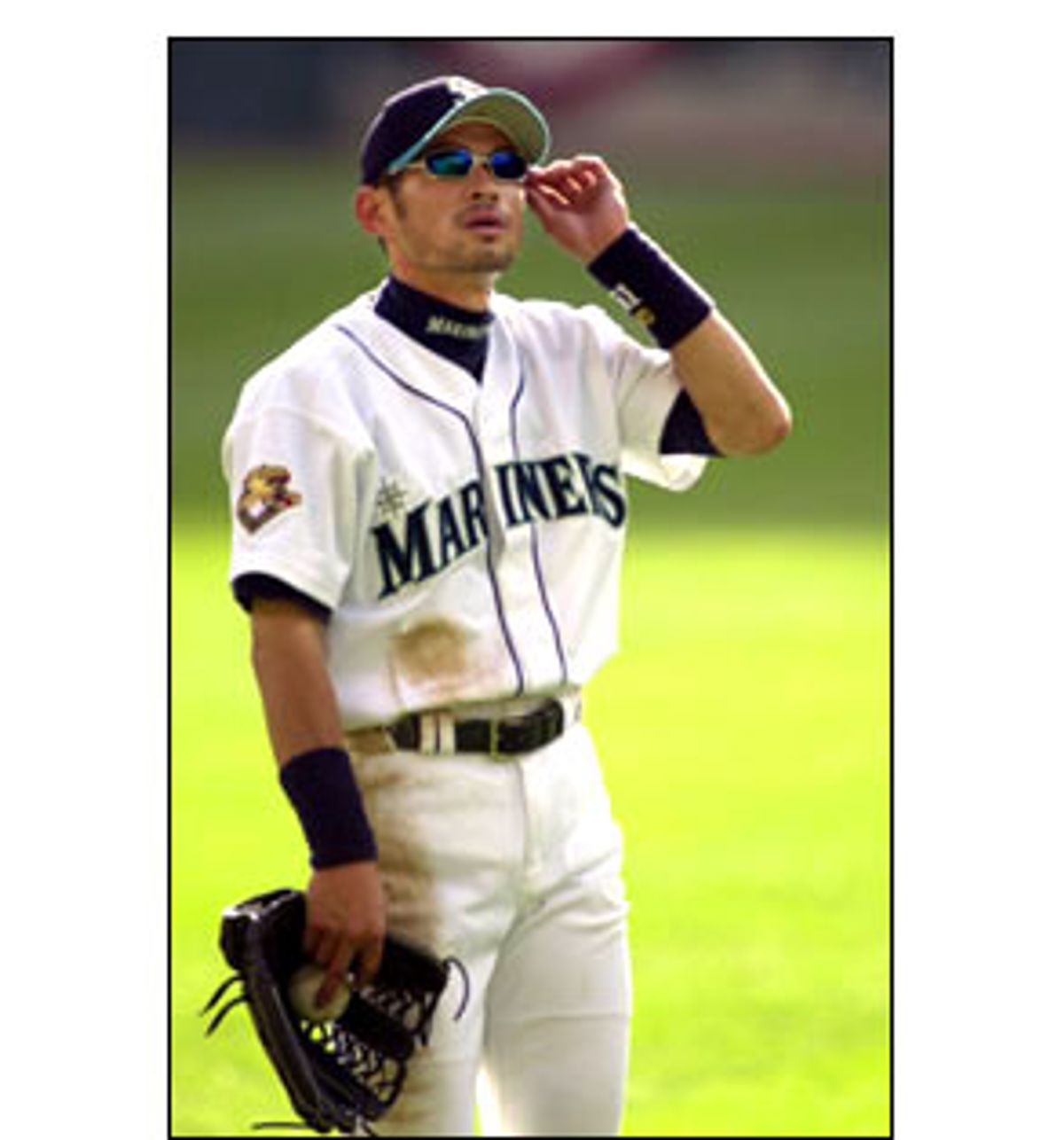

Here's another point that ought to have been debated but wasn't. Why did no one stick up for the New York Yankees' Bernie Williams as a legitimate All-Star center fielder? I like the Mariners' Ichiro Suzuki, too, but the guy has played exactly 85 games of big-league ball, while Williams has batted .305 for over 1,300 games, has driven in at least 100 runs four times in five years and has collected four World Series rings. Now, of the two, who has clearly demonstrated he is an All-Star? What exactly has Suzuki indicated that he does better than Bernie Williams, who, at the break, led him by 35 points in on-base average, 71 points in slugging average, and who had hit three times as many home runs?

The dumbest controversy is the mini-howl from fans and radio-show hosts that came down on Yankees manager Joe Torre for putting seven Yankees on the All-Star squad (including Williams). What is it with the fans and sports media today? Has ESPN reduced its memories to last night's highlights? Does no one recall that the Yankees have won four World Series in five years, and that they're in first place in the A.L. East this year? Gee, do you think it might have something to do with the players? The Yankees have won more games since 1995 than any team in baseball; what is wrong with rewarding the team's best players with a space in the dugout for the All-Star Game? Derek Jeter, Bernie Williams, Jorge Posada, Roger Clemens, Andy Pettitte, Mariano Rivera? Aren't these guys kind of, well, good? Haven't they proved it on the field, year after year? And if Rivera isn't going to pitch, is it so unfair that Mike Stanton get his spot? Isn't he an important part of baseball's best pitching staff?

Myself, I hope the sports press and at least a portion of the voting fans continue to stay dumb. It makes for great arguments every year.

Shares