The great political failure of the 1960s was the New Left's inability to bring the labor movement into its great liberationist tent. There were lots of reasons for that, one of them being that most big union leaders didn't want to be in that stinky tent with a lot of hippies, feminists, dashiki-wearing black militants and "fags." (That last comes from AFL-CIO leader George Meany's description of the New York delegation to the disastrous 1972 Democratic convention: "They've got six open fags and only three AFL-CIO representatives!") Also, not a small matter: The New Left opposed the Vietnam War; again, most labor leaders supported it.

Still, the inability to forge a political movement that was as much about class as race and gender rights haunts the United States today. We saw the shadows of that struggle even in the 2008 presidential campaign, as supporters of Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama traded charges of "racism" and "sexism," but few paid attention to the increasing openness of white working-class voters, especially men, to pick a Democrat again in a time of profound economic crisis. We see it today in the hostility of many Democrats, and the resistance of the Obama administration, to backing aggressive government action to address the continuing unemployment disaster. The decline of the labor movement hobbled the Democratic Party, and so far nothing has come along to replace it, to represent the great majority of Americans who are disadvantaged by the ever-increasing power of corporate America and the wealthy.

If you want to understand how we got here -- how the Democrats' New Deal coalition shattered in the 1970s, and why progressives are still picking the shrapnel out of their political hides -- you must read Jefferson Cowie's "Stayin' Alive: The 1970s and the Last Days of the Working Class." If you missed the 1970s entirely, or only remember it as a child or teen (as I do), you'll learn a lot. If you lived through it, you might come to think about it all very differently -- the missed opportunities, and what they say about our own time. Plus, this isn't an eat-your-spinach review, it's a fun read with cultural insight that makes connections I hadn't, from "Saturday Night Fever" to "Dog Day Afternoon," Bruce Springsteen to Devo.

Telling the story of how the New Left clashed with Big Labor to bring about the end of New Deal liberalism, Cowie is impossibly fair. Some accounts stress the conservatism (and racism and sexism) of labor bosses; others emphasize the New Left's contempt for mainly white union members and its preference for what came to be called "identity politics," the struggle of women, minority groups and gays for equal rights. Cowie reveals the extent to which both narratives have some truth.

"Stayin' Alive" also makes clear that the roots of intra-Democratic Party strife in the '60s can be found in the glorious New Deal of the '30s, which, to win the support of Southern Democrats, excluded agricultural and service workers from its new protections, including the National Labor Relations Act, leaving out many blacks as well as women. That led to strange inequities, such as a firm legally and successfully arguing it laid off workers because they were black, not because of union activism (the first was OK, the second was prohibited by federal law).

And once industrial unions were forced, whether by upstart organizers or federal intervention, to bring blacks and women into their ranks, the decline of industries like steel, mining and auto manufacturing created a zero-sum agony in which the worst nightmares of white unionists came true: Integration often came at the expense of white guys, as the number of overall jobs began to contract nationwide. But nobody won: While the percentage of black steelworkers, for instance, climbed during the '70s, the overall number of black steelworkers actually declined. Cowie in no way suggests the push to integrate those industries was a mistake (nor do I); it just suggests that the paranoia of the white working class, that minorities and women would take away their jobs, in some cases came true. As Cowie puts it: "Diversity arrived to American industry just as industry was leaving America."

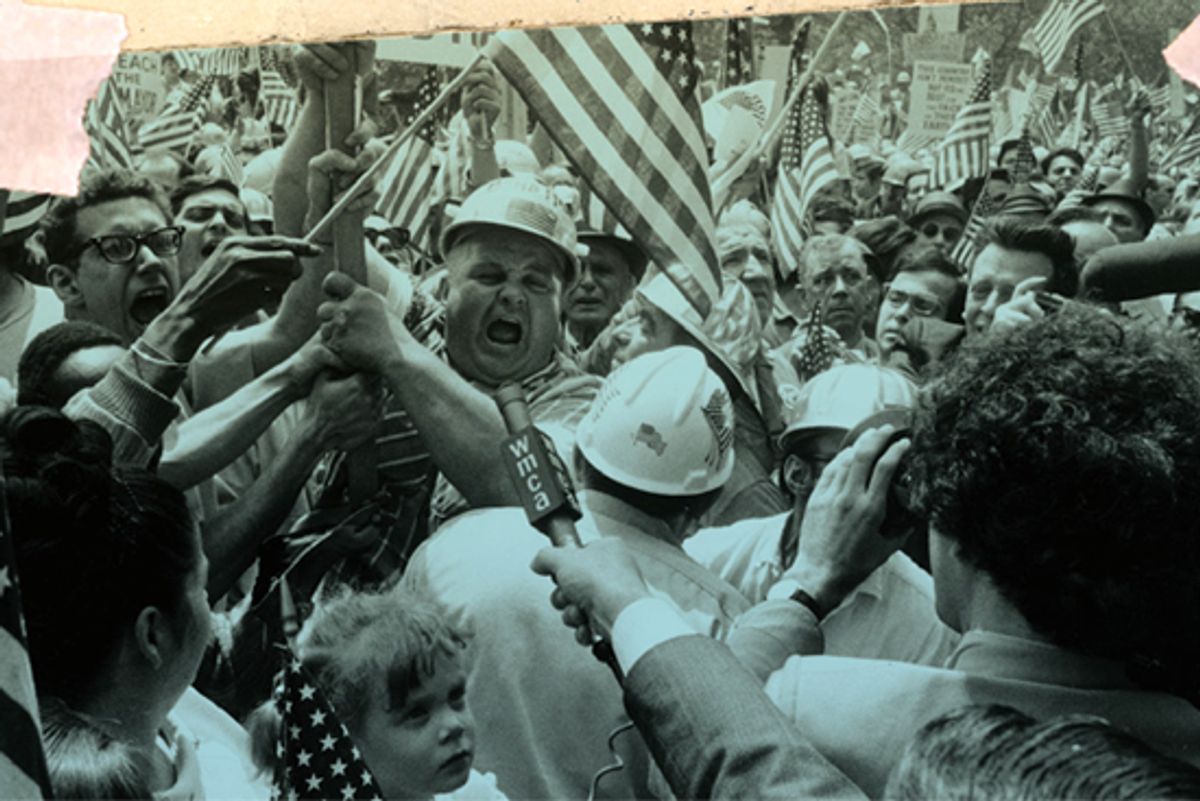

With their cultural and material standing on the wane, blue-collar workers drifted to the Republican Party, which came to represent a kind of identity politics for white working-class men. Cowie traces the story of Dewey Burton, an autoworker outside of Detroit who made the transition from Hubert Humphrey Democrat to George Wallace Democrat to Reagan Democrat in just about a decade. Frustrated with his job and his union, angry at Democrats for supporting mandatory busing to integrate the public schools, Burton became a symbol of the rightward drift of the white working class, profiled repeatedly by the New York Times. Nixon went after men like Burton in 1972, with a strategy of "cultural recognition" of their grievances while paying little attention to their economic travails. By the time of the notorious "hard-hat riots" of 1970, when construction workers beat up antiwar protesters near New York's City Hall, Nixon saw the promise of a blue collar-GOP alliance. The head of the building trades, Peter Brennan, did too; he went to the White House and presented Nixon with his own hard hat, and became secretary of labor in Nixon's second administration. While George Meany flirted with Nixon, he refused to endorse him -- but he did everything in his power to make sure George McGovern lost in 1972. As Cowie explains, "The majority of white working class voters [selected] Nixon by wide margins over the most pro-labor candidate ever produced by the American two-party system." The New Deal coalition was dead.

Just as voting Republican became a kind of identity politics for white working-class men who felt abandoned by Democrats, 1970s pop culture also detached the blue-collar worker from hoary notions of group pride and solidarity. On television and in movies, they were increasingly depicted as left-behind losers, whose only heroism derived from escaping their doomed brethren. Cowie contrasts that with the populism of Frank Capra, whose films always had heroes, but their heroism consisted in standing up for their family, friends and neighbors against attempts to abuse them, whether by government or business. In the late 1970s, working-class heroes from "Saturday Night Fever's" Tony Manero to the Bruce Springsteen of "Born to Run" could only prevail by leaving their roots behind ("It's a town full of losers and I'm pulling out of here to win," Springsteen sings to his lady in "Thunder Road," though later he would intentionally strive to represent and celebrate his working-class roots, not renounce them). Cowie's got an odd, funny meditation on disco, which actually managed to pull together the coalition the New Left never did -- blacks and women and "fags," as well as white working-class kids aping John Travolta. (I was the only one of my friends back in the day who loved disco and Springsteen.)

With Labor Day approaching, and President Obama preparing to make his annual bow to the labor movement, speaking at an AFL-CIO picnic on Monday, I had a long phone conversation with Cowie about his book, the Democratic Party's unraveling, and potential hope for the future. I asked him if he could pick the most disastrous single decision, by either a labor leader or a New Lefty, in the '70s, and he surprised me by doing so. Read on, and find out what it was.

Last week our interview with Tom Geoghahan about his book "Were You Born on the Wrong Continent?" (about why Europeans, particularly Germans, have it better than American workers) did incredibly well with our readers. I think there is this sense right now that our lives are tough, that we work harder than we used to, harder than in other countries, and we have so little security. And as I was talking about it with some younger colleagues here, and I brought up, "Well, y'know, we really don't have a big labor movement much to speak of in this country anymore."

And it fell like a brick on the conversation.

They're all smart people, it's not like they didn't know about the ancient labor movement, but nobody entirely recognizes the missing piece -- that there's no big movement agitating to make working conditions or economic conditions better for most people today.

Right.

So how did that happen?

That's a great question. (Laughs) There used to be a thing called the working class, and institutional representation of that group through the Democratic Party, through the ward system, through urban politics, through unions, and it also got wrapped up in the New Deal coalition. And that just shattered on the shores of the 1970s.

You've written a history of the Democratic Party in that period, because everything that went on within and around the labor movement hit the Democratic Party just as hard. There are two competing stories: Union leaders were racist, sexist dinosaurs, who were hostile to the new politics of women and minorities that was opening up, or else those dirty hippies and feminists and black power people hijacked the Democratic Party, deliberately left out the white working class, and now they deserve what they've gotten, a weakened party. You show there's truth on both sides.

Yeah. There is a rich moment of possibility where you almost see a reconciliation. In my first chapter, on the union insurgencies, you see [Steelworker union activist] Eddie Sadlowski, and [United Mineworker reformer] Arnold Miller, and Cesar Chavez, you see people who are sort of making peace with the new politics, and taking it into organizing, and trying to be more inclusive, but they're really fighting against a group of people within the union movement who feel they already won the game. The game is over, labor has won -- but they don't see everything's just eroding right out from underneath them.

It also became clear that it was a zero-sum game. Just as there were these insurgent movements, and just as we were as a society getting ready to deal with questions of equality and equal opportunity, just then, the economy began to contract. So it was true, in some industries, if you're going to give a job to a black worker or a woman, you're going to potentially be taking a job away from a white man. Growing up, I didn't believe that. I thought that was ...

Just racist crap.

... Just racist crap, and fear-mongering. But when you look at what was happening in the early to mid-'70s, say, in the steel mills, it was sadly kind of true.

Yeah, and just when the '60s make it to the Heartland, and some of those issues are really being dealt with by working people -- outside of the Berkeley, Ann Arbor, Madison, Columbia nexus -- there's this moment where they're confronting this, say, in a place like Lordstown [Ohio, the scene of a radical United Autoworkers strike], then bam, it all collapses. That's why I call the first epoch in the book "Hope amid the confusion," because it is this complex thing going on, that promises some hope, but it really is dashed, by 1974. And it leaves people with a lot of despair. Dewey Burton says we locked our dreams up and we turned the key, and despair was palpable in 1974. I've talked to many people that said, I was depressed for six months in 1974. It really was a miserable kind of moment, where you could feel it all change, and on top of it, Watergate, the OPEC oil shocks.

You also explain the way the New Deal set up some of this conflict by leaving out service and agricultural workers, largely blacks and women, from a lot of protections -- Social Security, the Wagner/labor relations act. Then, when we turn to the agenda of individual rights in the '70s, those protections get administered very separately, through the Civil Rights Act. So we created equal opportunity, but there was never an integrated approach to women as workers, or black people mainly in their economic context. The New Deal that we hail now built in that separation and segregation.

Definitely. I'm trying to get around this very common problem of pitting some ideal sense of class politics against identity politics, which is often the way the debate goes here. There's probably a little something to upset both sides on this. As this vibrant rights movement takes off, it really does present that zero-sum problem you were talking about. But then there are these ideas that show people were kind of aware of that moment. Like the Humphrey-Hawkins [full employment] Act. Now it just seems like crazy talk: "We can guarantee a job to everybody." But it provided a material foundation for everybody to be able to have economic rights.

If everybody's going to have equal opportunity, you are probably going to have to make sure you also expand opportunities.

Exactly right, and when the steel mills are closing, at the same time that blacks are getting positions in the steel mills, that's not going to do any good.

Well, let's go back to Humphrey-Hawkins, because I think that we're so far away from any conception of thinking about full employment acts that it's just so ...

Yeah, I mention the Humphrey-Hawkins Act to my students, and they're just like ... what? What planet are you from?

But even I, being from the same planet as you, think that the mechanisms that were needed to put it all together, at a time when people were, for lots of different reasons, not trusting government in the first place, it really was...

Oh, it was a total long shot.

Right.

But it passed! That's the weird thing; they built a bill and passed this thing. They weren't just laughed out of Congress. In fact, they had it killed by amendment and just evisceration, but there was enough interest in that to get it through. And yeah, I agree, it was unlikely, it was inflationary, but they did it. There was almost the same thing with labor law reform ... because this is right when people were talking about organizing the South again, and bringing minority workers and service workers and the rest into unions. And a retooled National Labor Relations Act really would have assisted in that. There's an alternative history there -- it's not a strong story, but there's possibility there.

You describe the politics of the Carter administration -- that he saw labor as a constituency that he had to talk to, but wasn't motivated by its struggles or accomplishments. But at least he felt like he had to pay lip service. When we get into the Reagan era, and we have guys like Dewey, our Reagan Democrats, the Democratic Party seems to lose all connection to what they used to stand for.

It becomes -- especially when the [Democratic Leadership Council] gets off the ground -- a reaction to Reagan. "Gosh, we really have to become more conservative." The party had working-class constituents, and many of their cultural values tend to be conservative, but their economic values have been very progressive. You look at a guy like [Nixon advisor and Southern Strategy architect] Kevin Phillips, who supported national health insurance, and stuff that now seems like ...

... complete socialism.

Exactly. There's a guy who parks near me in the faculty lot with a sticker that says, "Nixon: Now more than ever."

Right. He proposed a Family Assistance Plan, and ...

Yeah, exactly.

OSHA, EPA, and all these things Nixon did that Reagan tried to undo. It's also as if liberal Democrats felt they had to run away from unions: You talk about Gary Hart, McGovern's guy -- remember that he was re-created as an "Atari Democrat"? Whatever the hell that meant. But he was so burned by the unions trashing the McGovern campaign and the reforms of the Democratic Party, he said, "Screw labor." Watching all that unfold in your book is painful.

You're watching the wheels fly off the bus. (laughs)

And they're going to stay off forever.

Gary Hart's a classic example. He was big in the Democratic Party of the 1980s, he's important now, and he will hold a lifetime grudge against organized labor.

And why not? The fact that they thought they could just muscle past the 1972 Democratic delegate reforms and hold onto the power they had in '68? And pay no attention to these kids, or anyone else? I love the George Meany quote, "The New York delegation has six open fags!"

And yet, the interesting fact is, that kind of attitude is classic, but there were actually more union delegates than ever before. They just weren't all AFL-CIO guys -- and I mean guys.

Do you have one momentous bad decision on the part of a union leader, or a Democrat, or any political leader, when you look back at the complex ways that this all fell apart, and say, "This one was really bad." Could you pick just one?

I think you pinpointed it already, and that's the 1972 decision by organized labor, after all the convention rules changes (to open up to women and minorities), to destroy McGovern. Because that solidified a moment. It said, "We can't work with the unions," to the left, and to the women's movement and the rest. It said organized labor is just about guys like George Meany, and Mayor Daley, it's really the same monster, we can't deal with them. And that creates a natural alliance between the New Left and the New Democrats, who were much more sympathetic to important issues of diversity. But when unions came around, those leaders wouldn't be interested. So I really think that's the bad blood, because if you go back to '68, when Martin Luther King is assassinated, that was a terrible tragedy, but also, what a moment it was, where the unions and the civil rights leaders stand shoulder to shoulder for the Memphis sanitation workers strike. And then, by '72, everybody's out.

I've come to see the Tea Party as identity politics for white people. But you make me realize that long ago, the Republican Party became identity politics for white working-class men, it was the place where their grievances were paid attention to ... well, their cultural grievances, at least. It's amazing the whole way Nixon manages to co-opt so many of them while doing relatively little economically.

And so consciously, too.

He was really smart!

He really was ... he's my favorite character in all political history.

Really?

Yeah, he's so fascinating. Actually, I got a course evaluation once that said, "Great teacher," blah blah blah, "but he's got kind of a Nixon problem."

It was Nixon's great insight that you could pull a coalition together not about what we want, but what we don't want ... not "I have a dream," but "I have a grudge."

Who hates whom. (laughs)

Who hates whom, it's the foundation of modern politics.

Talk about the cultural stuff you found in the '70s, walk us through "Saturday Night Fever" and even Springsteen, who later takes back responsibility for representing the working class. But the Springsteen who became popular in 1975 is the guy who's gonna leave it all behind. The dreams you see projected on working-class people ... their only solution is to escape.

Well, since Mark Twain people have been getting out, "lighting out for the territories." But it was never with such a vengeance. There was never such a difference between the chosen ones and those who were left behind. And you clearly see that with "Born to Run." But what's new and different is the degree to which the communities they're leaving are relegated to the past. You never find out what's going to happen to those guys.

Yeah. It's not going to end well, and you're not really supposed to care.

It becomes much more about hero, spectacle, if you compare it to, say, Frank Capra movies of the '30s and '40s; it's a very different world. The community is there, but there's also the hero.

There the hero is saving the community.

Exactly.

So let's talk about the present, which is not that much more inspiring.

I keep thinking the pendulum has swung far enough on these issues on race that we can get back to talking about the economy, or infrastructure, and jobs, and healthcare, which would really bring together a broad coalition of working people. But it is unbelievable how toxic race can be. If you look at all the crazy stuff -- the Obama birther stuff is still alive out there, the Obama Muslim stuff, and then, of course, immigration. I think Nixon laid the paradigm for politics of fear and divisiveness. I think the '70s really are the paradigm for the current age. Just like the '30s created the paradigm for the postwar era, the '70s created the paradigm for the next decades. And I think part of writing this book for me was trying to lay that out so we can get it behind us.

I kept being struck by parallels between the '70s and today. You had 1974, Democrats are swept in by Watergate and hatred of Nixon; compare that to 2006, where Democrats surge thanks to Bush loathing and the reaction against the Iraq war. Two years later -- in '76 and '08 -- you elect a rather centrist Democrat. You have this line in the book about Carter winning because he made inroads with Republicans, because there was still a Republican backlash against Nixon. And I think that was true of Obama -- he had this fiction that he was going to create "Obamacans," and he did bring over some Republicans -- but it was because of the anti-Bush backlash, and a lot of them are now going back. I don't know what they're going back to; John Boehner and Mitch McConnell are no more inspiring than Bush, but these voters were culturally and politically Republican, and they're now ditching Obama. So I see these 1974-76/2006-08 parallels, in terms of the Democrats benefiting from the Republicans' screw-ups, but not being able to consolidate their gains.

Yeah. And also, then, choosing to play on their terrain. I think there's an almost unconscious sense that, OK, we got away with something here, we got elected, so we gotta be really careful. The Democrats seem to have been playing on the Republicans' playing field for the last generation, rather than trying to say, "OK, here's our agenda. Here's what we do ... if we're going to fail, let's fail on our agenda rather than their agenda!" Because Republicans are always going to do their agenda better. I think that haunts us.

To close, Obama's spending Labor Day with the AFL-CIO. What does that mean?

Not much, I don't think. [AFL-CIO president] Richard Trumka was just up here at Cornell, talking about all the great stuff that Obama's going to do -- they're sort of trapped, right? I know the type of person they would like to have in the presidency, but they feel they're not going to get him, so they're going to cheerlead for Obama. Obama's going to give them very little; I don't think Obama, for instance, was ever serious about the Employee Free Choice Act. And so the unions continue this pattern of shoveling out the money to the Democratic Party and getting very, very little back in exchange.

I don't want to end this on a note of pessimism. Who inspires you on the political labor front?

Well, I like the fact that Tom Geoghahan ran for Congress in Chicago. I thought that was pretty cool. And you know, one thing that I enjoy about Trumka quite a bit is that he can take complex economic issues, and boil them down into common sense as fast as anybody I know, and really spit it back at you, and you're like "Oh, OK, I got that." Which is something, because we tend to speak as technocrats. He does a good job of speaking English on a lot of these issues. I appreciate that very much.

During the campaign he gave an amazing speech to his union members, I saw it on YouTube, about if you're not going to vote for Obama because he's black ...

Oh, that was a brilliant speech. That was the first time I think that any leader of the AFL-CIO and probably any leader of any big union got up there and basically said the most cleansing and frank thing about race and labor that has ever been said. It was stunning.

What else makes you optimistic about positive change?

[Pause] What class politics could we have that gets us past the old politics, New Deal politics? We really are at square one in this economy; we need to let 1,000 flowers bloom and see what happens. One mistake labor made was, it really wasn't just about collective bargaining, you really needed to be part of other social movements, through the churches, with black groups and so on. Unions really for a time became the administrators of the postwar economic system, and they were proud of that. I remember Michael Harrington talking about Humphrey-Hawkins, and he said, "OK, that's fine, but nobody cares! Nobody's coming to meetings. Nobody's involved." Liberalism became something that happens to people from above, from the state -- and it's going to be a long time before that will happen again. We need to try something else.

Shares