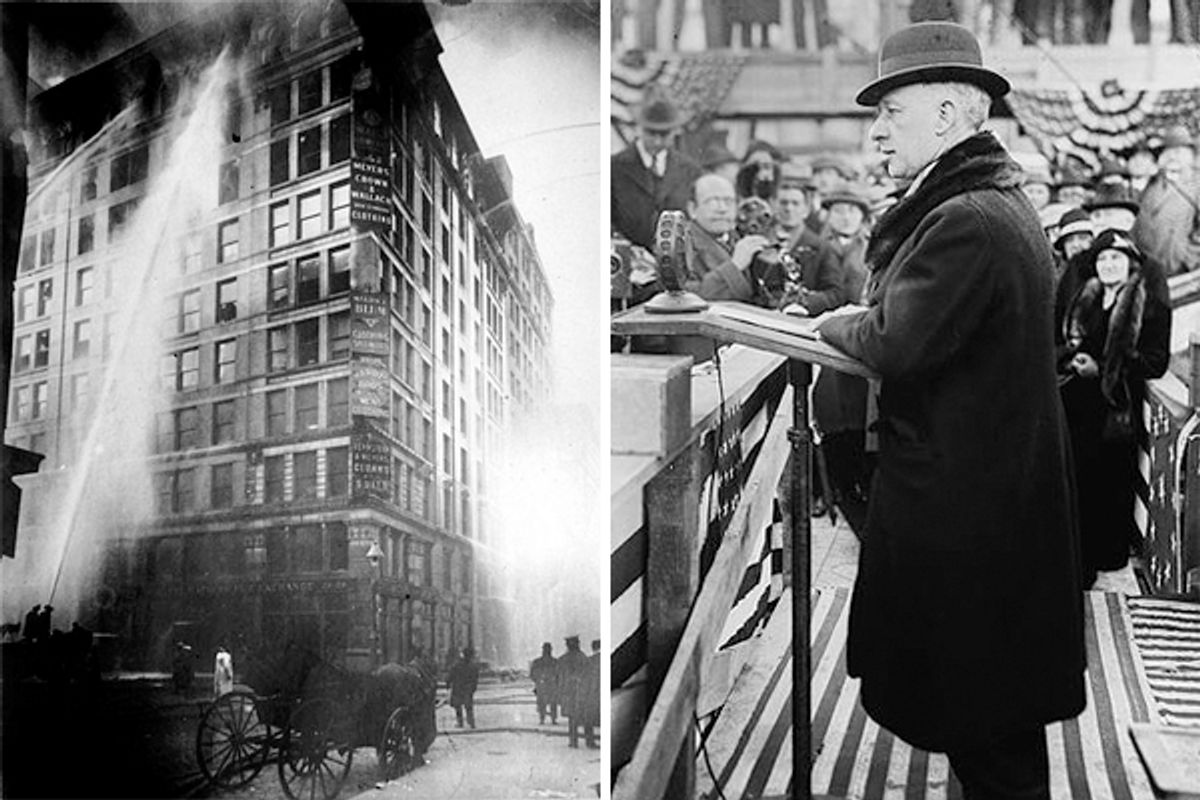

I wrote Wednesday about the unexpected widespread attention to the 100th anniversary of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire. It has a lot to do with post-Wisconsin agitation on the left and beyond. The tragedy is also genuine American history: No less an expert than Franklin Delano Roosevelt's labor secretary called March 25, 1911, "the day the New Deal began," and as the mother of the New Deal, Frances Perkins would know.

But because my upcoming book deals so much with the complicated political history of Irish Catholics in America, I've found myself fascinated by the figure of Al Smith, the New York Assembly majority leader who got himself appointed to the commission investigating the tragic fire, and later became the first Irish Catholic to run for president. If Perkins is the mother of the New Deal, Smith is at least an uncle, and maybe even the proud father. Roosevelt himself once said: "Practically all the things we've done in the federal government are the things Al Smith did as governor of New York." Smith, of course, became the New York governor and the 1928 Democratic presidential candidate, and then lost in a landslide to Herbert Hoover. After he surrendered the 1932 nomination battle to FDR, he grew bitter and more conservative as he aged, so his legacy as a progressive hero has been obscured. Still, I think there are lessons about our present political mess in the story of Smith, Roosevelt, the Triangle fire and the New Deal.

If you don't already know the details, the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire horrified New York, hundreds of whom watched as 146 workers, the vast majority of them young Jewish and Italian immigrant women, either burned or jumped to their death from the factory's locked-up 9th floor sweat shop. The fire escapes were a joke and fell apart when used; doors were locked to funnel the girls out one exit to make sure they weren't stealing; there was no sprinkler system, and while the fire department responded promptly, their ladders only reached the sixth floor. Tragically, Triangle workers had voted to unionize two years earlier, but the owners locked them all out. That led to a historic four-month strike by 20,000 garment workers that resulted in the unionization of many garment-industry businesses -- except Triangle.

Frances Perkins, then a social worker, saw the tragedy in person, horrified as she watched girls leap to their deaths from the burning factory as she stood in Washington Square. In 1964 she recalled:

The people had just begun to jump when we got there. They had been holding until that time, standing in the windowsills, being crowded by others behind them, the fire pressing closer and closer, the smoke closer and closer. Finally the men were trying to get out … a net to catch people if they do jump, there were trying to get that out and they couldn't wait any longer. They began to jump. The window was too crowded and they would jump and they hit the sidewalk. The net broke, the weight of the bodies was so great, at the speed at which they were traveling that they broke through the net. Every one of them was killed, everybody who jumped was killed. It was a horrifying spectacle.

(Note to history wonks: the Cornell University Triangle fire site where the Perkins talk resides is a dream come true.)

New York Assemblyman Al Smith had been traumatized by the fire. Smith's Tammany Hall machine was dominated by the Irish, and the Triangle victims were Jewish and Italian. There were four Bernsteins, four Goldsteins, four Rosens; three Malteses, two Miales and two Saracinos on the list of the dead, not an Irish name among the 146 victims. But many lived in Smith's Lower East Side neighborhood, and he went to visit their survivors. Perkins tells the story:

He did the most natural and humane thing. As he said: "Why I did it just as I would if they had died of anything else, you know, you go to see the father and mother to try to help them." He went to the places where they lived; he went to the tenement they had occupied to see their father and mother and tell them how sorry he was or their husband, as the case might be, or their wife, to tell them of his sympathy and grief. It was a human, decent, natural thing to do and it was a sight he never forgot. It burned it into his mind. He also got to the morgue, I remember, at just the time when the survivors were being allowed to sort out the dead and see who was theirs and who could be recognized. He went along with a number of others to the morgue to support and help, you know, the old father or the sorrowing sister, do her terrible picking out.

A few days later, there was a community meeting at the Metropolitan Opera House, Perkins recalled, where union leader Rose Schneiderman, who became a leader of the influential Women's Trade Union League, riveted the audience with her white-hot anger and her refusal to make nice with the civic luminaries in attendance. We could use a few Rose Schneidermans today:

I would be a traitor to these poor burned bodies if I came here to talk good fellowship. We have tried you good people of the public and we have found you wanting. The old Inquisition had its rack and its thumbscrews and its instruments of torture with iron teeth. We know what these things are today; the iron teeth are our necessities, the thumbscrews are the high-powered and swift machinery close to which we must work, and the rack is here in the firetrap structures that will destroy us the minute they catch on fire.

This is not the first time girls have been burned alive in the city. Every week I must learn of the untimely death of one of my sister workers. Every year thousands of us are maimed. The life of men and women is so cheap and property is so sacred. There are so many of us for one job it matters little if 146 of us are burned to death.

We have tried you citizens; we are trying you now, and you have a couple of dollars for the sorrowing mothers, brothers and sisters by way of a charity gift. But every time the workers come out in the only way they know to protest against conditions which are unbearable the strong hand of the law is allowed to press down heavily upon us.

Public officials have only words of warning to us – warning that we must be intensely peaceable, and they have the workhouse just back of all their warnings. The strong hand of the law beats us back, when we rise, into the conditions that make life unbearable.

I can't talk fellowship to you who are gathered here. Too much blood has been spilled. I know from my experience it is up to the working people to save themselves. The only way they can save themselves is by a strong working-class movement.

Galvanized by the tragedy, and by the anger of the union and its supporters, Smith and Perkins backed the establishment of an investigative committee appointed by the New York State Legislature. State Sen. Robert Wagner became its co-chair. Over a remarkable four-year period they examined conditions at Triangle and at a wide swath of city sweatshops, and came up with sweeping legislative reforms. Smith and Wagner passed a stunning wave of strong pro-labor legislation, creating new health and safety codes as well as restricting child labor and shortening the work week for women (to 54 hours), even trying (but failing) to impose a state minimum wage.

Business interests fulminated against the Smith-Wagner agenda. A representative of the Associated Industries of New York insisted that the new laws would mean "the wiping out of industry in this state." Smith took the criticism in stride, telling Perkins: “I can't see what all this talk is about. How is it wrong for the State to intervene with regard to the working conditions of people who work in the factories and mills? I don't see what they mean. What did we set up the government for?"

"What did we set up the government for?" That's a provocative question. Even many Democrats, the inheritors of Smith's New Deal, seem not to have an answer today.

-----------------------------

Thanks to their prominence on the Triangle Commission, Smith would become New York's governor and Wagner would become senator. Maybe most important, Smith had begun to assemble the urban New Deal coalition by reaching out to Italians and Jews who'd previously been neglected by Tammany. "Immigrants and city dwellers recognized that he was someone in his politics who stood up for them, accepted them as equals and above all, who gave them respectability," his biographer Robert Slayton wrote. Triangle fire historian David Von Drehle concluded that thanks to Smith's outreach and reform legislation, "In the generation after the Triangle fire, Democrats became America's working class, progressive party." As governor, Smith surrounded himself with Triangle commission veterans like Frances Perkins, Belle Moskowitz and Abram Elkus and continued to pioneer innovative social legislation.

In 1928, the popular New York governor would commence his doomed run for president as the Democratic candidate. The man who'd stood up to the Ku Klux Klan began to interest black voters, hinting at the multiracial New Deal coalition that would later emerge. Smith cultivated NAACP leader Walter White and played up his tough stance against the KKK. But his perceived need to keep the "Solid South" Democratic limited his outreach to black voters, and his selection of segregationist Arkansas Sen. Joseph Robinson as his vice president alienated them further. Still, black newspapers like the Baltimore African American and the Chicago Defender endorsed Smith, the NAACP's White personally (if tepidly) backed him, and a young civil rights organizer named Bayard Rustin volunteered for him as well. Smith would get a record number of black votes in Philadelphia and other Northern cities, and the GOP share of the black vote declined about 15 percent from 1924 to 1928, the first strong sign that African-American voters might be available to the Democrats, who had been the party of slavery 75 years before.

But the incipient New Deal coalition wasn't enough to defeat Hoover in 1928. Smith was the right man to pull together immigrant New York and what would become the urban Democratic base over the next 40 years -- starting with the previously warring Irish, Italians, Jews and blacks. The astute pollster Samuel Lubell would describe it as the "Al Smith revolution," which led to the pro-Democratic realignment that reshaped the country from 1928 through the Nixon backlash of 1968 (interrupted by an Eisenhower rest stop in the '50s). But most of the nation wasn't yet ready for an Irish Catholic president. The great Richard Hofstadter wrote that no Democrat could have beaten Hoover, given the country's neo-Gilded Age, faux-prosperity on the eve of the Great Depression. But its clear bigotry played a role in Smith's defeat, making a certain loss into a landslide. With Prohibition still the law of the land, Smith was a "wet," and he was widely depicted as an Irish drunk. Anti-Smith leaflets and jingles blanketed America: "Popery in the Public Schools," "Crimes of the Pope" and "Convent Life Unveiled" were just a few. A rhyme I heard about long ago stayed in my memory:

A vote for Al is a vote for rum,

A vote to empower America’s scum ...

Let Historians write, "Smith also ran"

Now it’s time to support the Ku Klux Klan.

Antipathy against Smith wasn't confined to KKK backers. Progressive movement editor William Allen White, who had himself fought the Klan in Kansas, warned: "The whole Puritan civilization which has built a sturdy, orderly nation is threatened by Smith."

In the wake of his 1928 defeat and his later rebuff at the 1932 Democratic convention in favor of FDR, a kind of ethnic and class bitterness overtook Smith, and the larger Irish Catholic community that revered him. The former New York governor would endorse Roosevelt after their nomination battle that year, and watch his old colleague Robert Wagner work with FDR and Frances Perkins to bring many New York innovations to Washington, D.C. Wagner's name is on the landmark Labor Relations Act that led to the explosion of unionization over the next two decades; he was also crucial to establishing Social Security, two reforms Smith supported.

Yet the man FDR had labeled "The Happy Warrior" would war with his old friend and endorse Republican Alf Landon. Smith would reconcile with Roosevelt at the start of war in 1941, but he continued to rail at the "cold, clammy hand" of bureaucracy and insist FDR was anti-business. My grandparents came from Cork, Ireland, the year of Smith's defeat, and for all the opportunity they found here, his loss was like a door slamming in their face. In "Beyond the Melting Pot," Daniel Patrick Moynihan explains it this way:

The bitter anti-Catholicism and the crushing defeat of the 1928 campaign came as a blow. The New York Irish had been running their city for a long time, or so it seemed. They did not think of themselves as immigrants and interlopers with an alien religion; it was a shock to find that so much of the country did. Worse yet, in 1932, when the chance came to redress this wrong, the Democrats, instead of renominating Smith, turned instead to a Hudson Valley aristocrat with a Harvard accent [Roosevelt].

The well-to-do Irish turned on Harvard and Roosevelt; the lower classes fell prey to Father Coughlin, who early on fought the Ku Klux Klan in Michigan, backed Smith and FDR and called the New Deal "Christ's deal" -- and then became a reactionary anti-Semite railing against Roosevelt, the Jews and Wall Street.

Still, it's sad that Smith's role in the New Deal has been obscured, partly by his own rightward evolution after his presidential loss. I've also wondered if it has to do with the reactionary anti-Irish attitudes that took hold of much of the left thanks to the "whiteness studies" scholarship of the last 15 years, in which a slew of left-wing scholars, none of them Irish, have indicted Irish Americans as uniquely responsible for American racism and the failure of multiracial coalition-building ("How the Irish Became White" is the bible of this point of view, but even Nell Irwin Painter's otherwise interesting "A History of White People" judges the Irish, unfairly in my view, as uniquely racist.) This is a debate that currently rages in books and academic journals and can't be adequately addressed here (I'll do my best in my own book); suffice it to say that I'm frustrated to find that the left often does as much as the right to minimize and belittle its own potential constituency. In order to convict the Irish of bigotry that made multiracial organizing impossible, the whiteness studies tomes ignore the role of Irish labor radicals central to the Progressive era and the New Deal, from Leonora O'Reilly, a founder of the Women's Trade Union League (which backed the Triangle strikers) as well as the NAACP; Mary Kenny O'Sullivan, another WTUL founder who backed the 1912 Lawrence strike; New York Irish Catholic abolitionists Patrick Ford, Fathers Thomas Farrell and Edward McGlynn, who pastored St. Joseph's Church in Greenwich Village; McGlynn's parishioner Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, an IWW founder; Flynn's IWW comrades Big Bill Haywood and Father John Hagerty, Mother Mary Harris Jones ... well, you get the picture.

Of course, it's also impossible not to notice how thin-skinned many once-progressive Irish leaders have turned out to be, how easy it's been to flip them rightward if their own ethnic struggles aren't adequately acknowledged, from Smith to Coughlin to Bronx Irish Catholic AFL-CIO president George Meany, who shattered the New Deal coalition once and for all by refusing to endorse the most pro-labor Democrat ever, George McGovern, in 1972. The whiteness studies folks didn't fictionalize Irish reactionaries; they're real. Pat Buchanan's father was an Al Smith supporter who followed his candidate right. Today we're stuck with Buchanan, Bill O'Reilly and Sean Hannity as the face of Irish-American conservatism. But Al Smith doesn't belong in their company; the "Happy Warrior" was a class warrior, at least for a time, and as we remember the progressive legacy of the Triangle fire, we should remember Smith's as well.

---------------------

And what does all this have to do with President Obama, since I put his name in the headline even before I wrote the piece, so badly did I want it to inform the way we think about our Democratic Party crisis today? In 2008 I thought our first black president, like our first Irish Catholic nominee, might put together an enduring, innovative and realigning coalition: young people, blacks, Latinos and Asians, women, union members, genuine independents, college graduates; a post-New Deal progressive majority. But without a strong class-based pitch, in the middle of the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression, Obama's appeal has turned out to be somewhat hollow, his support sometimes thin. Despite his much-lamented troubles with white working-class voters, most of whom backed Hillary Clinton in the primary (and were dismissed as racists), in the end Obama won the votes of white union members overwhelmingly in 2008. (Given the decline in union membership, that's not the same as the white working class, but it's still an important bloc.)

But white workers' skepticism about the centrist Obama persisted, and was reinforced by Obama's compromised agenda, which barely infringed on the prerogatives of the financial, insurance and real estate interests that backed him -- the interests known as the FIRE sector, by the way. (Of course, any resonance with the Triangle fire tragedy, like any resemblance with a real person or persons living or dead, is coincidental.) So those white unionists turned out in lower numbers in the 2010 election and voted less reliably Democratic, and in 2012, they're up for grabs. In Obama's electoral equation they may seem too few to matter, but post-Wisconsin, they’ve got more political standing now than they did in 2008.

I expect Obama to win them in 2012, and win the presidency, because he's likely to be blessed with hideous opponents. But I don't see him or anyone around him thinking about how to rebuild the Democratic Party, long-term, around a new vision of a fair and prosperous economy. The Triangle fire anniversary has gotten national attention because in the wake of the Wisconsin battle – echoed in other states like Ohio, Michigan, New Jersey and now Maine -- people are realizing that with unions on the decline, plutocrats like the Koch brothers calling the shots, and the Democratic Party either MIA or cozying up to Wall Street, most of us are unprotected from corporate caprice or cruelty that can lead to disaster.

So I'll be interested to see which Democrats show up at the memorial in New York on Friday. A lot of them could stand to be reminded of how they became a multigenerational ruling national party 75 years ago, thanks to Al Smith -- and how they might do it again.

Shares