The White House released video of a formerly private meeting President Obama held with a group of college students in Boston last March, where he discussed the importance of political compromise. Some of the students were active in college Democrats and Republicans groups, others were independents, and the talk is widely being seen as emblematic of the president's conciliating world view – and how he disappoints the unrealistic left, and is proud to do so. I wouldn't pay much attention to it if it was just a normal four-minute daily news item, which flow on all day, every day. But since the White House seems to think it's politically useful, it's worth taking seriously.

The big headline from the president's little talk is that he bashed the Huffington Post – twice! First, he told the college Republicans in attendance that he knows they consider him a liberal president, while "if you read the Huffington Post, you'd think I was some right-wing tool of Wall Street. Both things can't be true." But I was much more interested in Obama's later comments about Abraham Lincoln and the Emancipation Proclamation, because he captures a complexity that's often missed by people on the left – but he misses some complexity, too.

Obama explained that even though Lincoln opposed slavery, his Emancipation Proclamation only freed the slaves in states that were fighting against the Union; it didn't apply to slave states that were Union allies. Obama's not pointing that out to call Lincoln a hypocrite or malign his commitment to eradicating slavery; he's describing it as a savvy pragmatism, a leader understanding the limits of his time. "Here you've got a wartime president who's making a compromise around probably the greatest moral issue that the country ever faced because he understood that `right now my job is to win the war and to maintain the union,'" Obama told the students.

I agree with his assessment of Lincoln's values, and Lincoln's cautious pragmatism. But then Obama went a little too far.

"Can you imagine how the Huffington Post would have reported on that? It would have been blistering. Think about it, `Lincoln sells out slaves.'"

I have two issues with Obama's argument. First, some of the media coverage of Lincoln's emancipation compromise was in fact "blistering." The Commonwealth, an abolitionist journal in Boston, blasted Lincoln's move as "confused and almost contradictory." It went on:

It must have required considerable ingenuity to give two and a half millions of human beings the priceless boon of Liberty in such a cold ungraceful way. The heart of the Country was anticipating something warm and earnest. One could scarcely imagine that the herald of so blessed a dawn should have caught none of its glow. Was it not a time when some word of welcome, of sympathy, of hospitality for these long-enslaved men and women, might have been naturally uttered. Was it not a time for congratulating the liberated millions that the President of the Universe had opened the portals on which had been hitherto the padlock of the Constitution, which no terrestrial President could touch? But instead of an embrace we had a gruff, "Stay where you are!"

The New York Tribune's Horace Greeley repeatedly criticized Lincoln for tarrying on emancipation, most famously with an 1862 open letter in his paper, "The Prayer of Twenty Millions," in which he told Lincoln that he was "sorely disappointed and deeply pained by the policy you seem to be pursuing with regard to the slaves of rebels." When Lincoln finally issued his Emancipation Proclamation, Greeley praised it. But the editor then began to sour on the bloody war itself, as well as the way Lincoln was fighting it it, and he undermined the president by publicly seeking ways to end it.

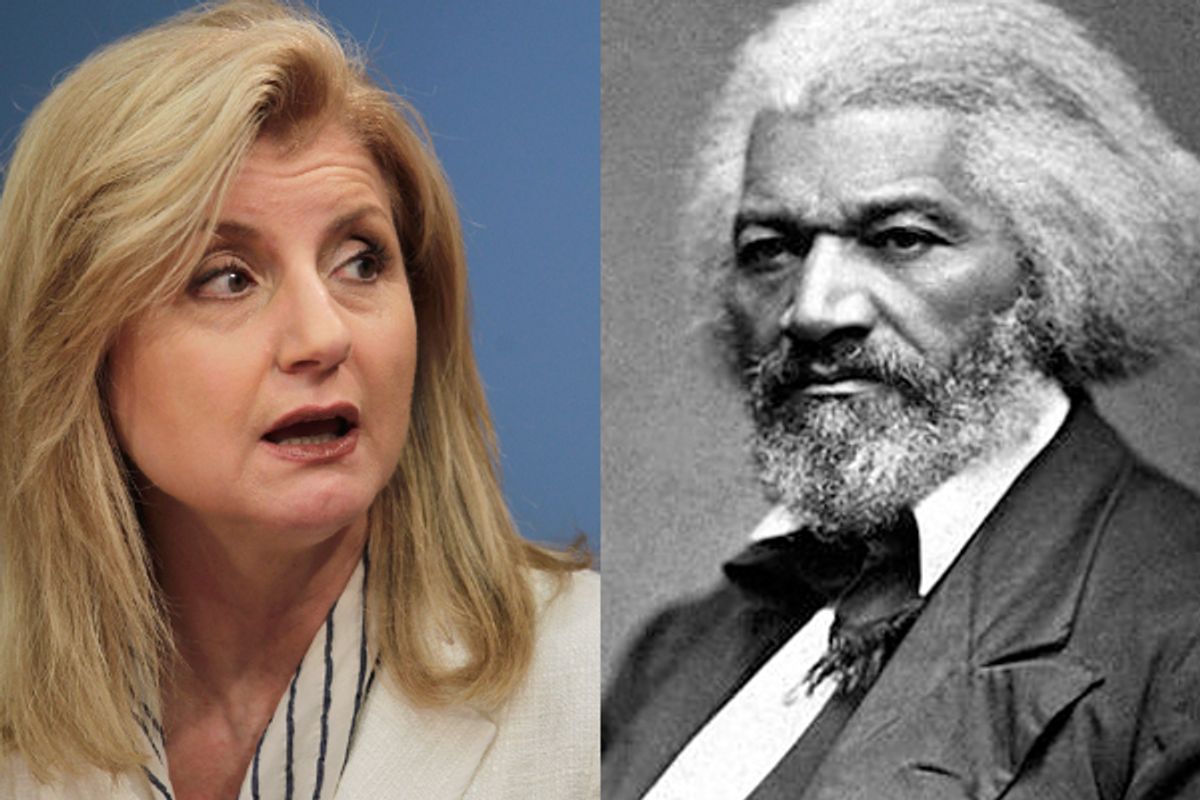

So news and opinion journals of Lincoln's day that shared Lincoln's larger goal of emancipation for all slaves did indeed criticize the president's sometimes halting moves on slavery. I also have a problem with the notion that the Huffington Post represents liberals, progressives, or their interest groups. The Huffington Post is a business, and Arianna Huffington, who's been an entrepreneur of ideas, and of herself, since Obama was a college student, shouldn't be used as a stand-in for the left. It makes a kind of perverse sense, though, that the president would see it that way, since the Huffington Post was a house organ of the Obama-supporting left during 2008. Its reasons were part principle and part positioning, as Obama's Web-centric campaign created an instant audience for a pro-Obama lefty news source. Oh well. Arianna giveth, and Arianna taketh away. I'm really not sure why the president reads much into any of that.

But there's a deeper problem here: The fact that pundits and talking heads have become a stand-in for a politically engaged left. I watched GOP macher Grover Norquist on "Hardball" Monday; he was terrible. I realized I hadn't seen much of Norquist on TV before, and he's really not very good at it. But why should he care? By forcing his no new taxes pledge on Republicans, via Americans for Tax Reform, he's become one of the most powerful men in the country. I'm trying to think of Democratic activists who have had a comparable impact their party, and I can't. Instead, the relationship of the Democratic base, and progressives, to Obama and to his constituency is weirdly defined by talking heads, whether Huffington or Keith Olbermann or Rachel Maddow or Chris Matthews or the welcome new addition, perhaps temporary, of Rev. Al Sharpton to the MSNBC lineup.

While we're thinking about the gulf between pundits, and activists and leaders, it's worth noting Frederick Douglass's point of view on Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation. It's complicated, as befits Douglass's passion combined with his long-view pragmatism, which we all should work to combine. In his memoir, Douglass wrote about anxiously awaiting the proclamation in Boston, with a group of abolitionists. Some feared Lincoln might not even go through with it, he admitted, describing the 16th president in words that today he might use to describe our own: "Mr. Lincoln was known to be a man of tender heart, and boundless patience; no man could tell to what length he might go, or might refrain from going in the direction of peace and reconciliation." Douglass and his Boston group rejoiced when word of the proclamation came through. As he wrote at the time, "We shout for joy that we live to record this righteous decree."

Then came some disappointment. "Further and more critical examination showed it to be extremely defective," Douglass recalled in his memoir. "It was not a proclamation of "liberty throughout all the land, unto all the inhabitants thereof," such as we had hoped it would be; but was one marked by discrimination and reservations." Douglass and other black abolitionists also criticized Lincoln's decision to pay black soldiers who enlisted to fight for the Union a lesser wage than white soldiers. They wanted Lincoln, who they admired, to do more, and do it faster.

So rather than Lincoln enjoying journalists and advocates applauding his compromises on slavery and his uneven treatment of black soldiers, he in fact faced criticism and opposition at every step along the way. In fact, it's hard to imagine the long effort to eradicate slavery without an abolitionist movement, pushing harder, advocating tougher tactics, even sometimes violence, along the way. Obama seems to either misunderstand or reject political models in which passionate partisans push for bold change, and force or enable their leaders to resist capitulating to the other side.

In the end, I think the president gave the young politicos some bad advice about politics, as he pointed to compromise as perhaps the best embodiment of political spirit. "Don't set up a situation where you're going to be disappointed," he told them. Hmmm. How can you avoid that? Politics breaks your heart, if you have strong values. Obama is right that compromise is essential. But if you care deeply about issues and policies and principles, well, you're going to be disappointed, and that's OK. Compromise is crucial, but so is dissent, and maybe even disappointment too. Obama, the prophet of compromise, sometimes seems to be trying to wish away the rough and tumble reality of politics, the clashing of interests, the genuine disagreements about important policy decisions, and the real disappointment one feels when something you care about deeply gets compromised away. Disappointment can drive you from the process, which isn't good; it can also help you resolve to fight harder and smarter next time, and win.

Meanwhile, across the aisle, there's a vivid example of how dissenters and unyielding partisans and people unafraid of disappointment can move the country in the direction they want to take it. The debt ceiling crisis is a scandal, but you have to politically admire the 2010 House freshmen who have caused the crisis. They genuinely believe government is too big. They genuinely believe cutting government, and taxes, will liberate the free market to put people back to work and end this economic slump. Let's leave aside the fact that there's no evidence for these beliefs, and treat the beliefs as sincere. The House GOP hardliners either don't believe there will be a debt crisis, or else they believe the crisis will hit, but that it's long overdue, and in the end, after a little economic and maybe even political suffering, it will bring about the world they would like it to create.

That is scary apocalyptic thinking, to me, but it's also politically effective. They don't want to compromise, or take their marching orders from their leaders, because they believe their leaders are part of a dysfunctional bipartisan alliance that's created these deficits. And they're right. A small part of me sympathizes with the Tea Party zealots, watching John Boehner and Mitch McConnell trying to humor them, even trick them, into ultimately caving on the debt issue. So as early as Tuesday, they'll let them vote for the preposterous "Cut, Cap and Balance bill," which will fail, and then, having once it's failed, party leaders will sorrowfully force the rank and file to go for whatever deal they broker with Democrats. Or at least they'll try to. It's possible that their transparent manipulations will backfire. What if the Tea Party freshmen realize they're being played, and refuse to play along? I have real questions about whether the GOP leadership can really ever broker a deal that brings along a majority of these freshmen. Stay tuned.

And what about our side of the aisle? The president has promised to reject any deal that contains only spending cuts, no revenue increases. Let's hope he sticks to that. One thing that would strengthen his resolve might be Democrats to his left who won't vote for such a deal even if he says he backs it. Yes, they would be joining the GOP extremists in playing chicken with the debt ceiling, but it's worth playing that out for a while. Obama should have to deal with hard-liners in his own caucus, the way Boehner and McConnell do, so he can say with honesty that his hardliners, like theirs, make a complete cave-in impossible. It might not work, but it would be fun to watch.

On the other hand, what if all Democrats accept the president's enshrining compromise itself as a high political value, not just a means to an end but an end in itself? In this battle, that would set us up for spending cuts that not only hurt the people we most care about, but probably hurt most Democrats politically, killing jobs and sucking more demand out of an economy already stalled by the lack of demand. There's are points where it's clear that Obama is reckoning with genuine political reality, and employing maturity and sobriety along the way. Then there's a point where you wonder: Is the president's commitment to compromise accomodating political reality, or creating political reality? Is he narrowing the range of choices on the table for Democratic leaders, and voters, to advance? I don't have an answer, but it's a question worth asking.

It's almost exactly a year ago that David Axelrod, who'd been a voice for populism and economic toughness as the administration pulled the country out of the recession, joined the side of the deficit hawks. Did he see economic data or hear arguments that made him decide that the deficit ought to be front and center? No, he told the New York Times that he'd noted more worry in the public mood over the deficit. "It's my job to report what the public mood is," he told the Times. "I've made the point that as a matter of policy and a matter of politics that we need to focus on this, and the president certainly agrees with that." Again, was that reckoning with political reality, or creating it? I'd argue it was the latter. And now a Democratic president with 9.2 percent unemployment doesn't have any political or economic or moral cover to pivot unapologetically back to a jobs agenda.

At any rate, the debt ceiling crisis continues interminably. I talked about all of this on MSNBC's "The Ed Show" tonight with the Washington Post's E. J. Dionne.

Visit msnbc.com for breaking news, world news, and news about the economy

Shares